![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

1.1 A Historical Background to Metal Aquatic Chemistry

In terrestrial waters, much of the initial work by environmental engineers and scientists was aimed at understanding the processes of waste water treatment, and of the reactions and impact of human-released chemicals on the environment, and on the transport and fate of radioactive chemicals. This initial interest was driven by the need to understand industrial processes and the consequences of these activities, and the recognition of the potential toxicity and environmental impact of trace metals released during extraction from the Earth as well as during refining and use. Initial interest in the chemistry of the ocean was driven by the key question of why the sea is salty. Of course, it is now known that freshwaters, and even rainwater, contain a small amount of dissolved salts; and that the high salt content of the ocean, and some terrestrial lakes, is due to the buildup of salts as a result of continued input of material to a relatively enclosed system where the major loss of water is due to evaporation rather than outflow. This is succinctly stated by Broecker and Peng [1]: “The composition of sea salt reflects not only the relative abundance of the dissolved substances in river water but also the ease with which a given substance is entrapped in the sediments”.

The constituents in rivers are derived from the dissolution of rocks and other terrestrial material by precipitation and more recently, through the addition of chemicals from anthropogenic activities, and the enhanced release of particulate through human activity. The dissolution of carbon dioxide (CO2) in rainwater results in an acidic solution and this solution subsequently dissolves the mostly basic constituents that form the Earth’s crust [2]. The natural acidity, and the recently enhanced acidity of precipitation due to human-derived atmospheric inputs, results in the dissolution (weathering) of the terrestrial crust and the flow of freshwater to the ocean transports these dissolved salts, as well as suspended particulate matter, entrained and resuspended during transport. However, the ratio of river to ocean concentration is not fixed for all dissolved ions [3, 4] as the concentration in the ocean is determined primarily by the ratio of the rate of input compared to the rate of removal, which will be equivalent at steady state. Thus, the ocean concentration of a constituent is related to its reactivity, solubility or other property that may control its rates of input or removal [1, 5].

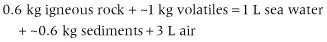

Many of the early investigations looked at the aquatic ecosystem as an inorganic entity or reactor, primarily based on the assumption that aquatic chemistry was driven by abiotic chemical processes and reactions, and that the impact of organisms on their environment was relatively minor. In 1967, Sillen [6], a physical chemist, published a paper The Ocean as a Chemical System, in which he aimed at explaining the composition of the ocean in terms of various equilibrium processes, being an equilibrium mixture of so-called “volatile components” (e.g., H2O and HCl) and “igneous rock” (primarily KOH, Al(OH)3 and SiO2), and other components, such as CO2, NaOH, CaO and MgO. His analysis was a follow-up of the initial proposed weathering reaction of Goldschmidt in 1933:

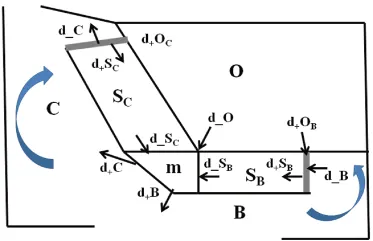

Sillen stated that “the composition may … be given by well-defined equilibria, and that deviations from equilibrium may be explainable by well-defined processes”, and proposed the box model shown in Fig. 1.1 [6]. However, he also stated that this did not “mean that I suggest that there would be true equilibrium in the real system”. In reality, the ocean composition is a steady state system where the concentrations are determined primarily by the relative rates of addition and removal, and that reversible equilibrium reactions are not the primary control over ocean composition [1]; something Sillen [6] alluded to. The major difference between these two conceptualizations is that the equilibrium situation would lead to a constancy of composition over geological time while the steady state model accommodates variation due to changes in the rate of input of chemicals to the ocean. The Sillen paper established the idea that the ocean was a system that could be described as being at geological equilibrium in terms of the major reactions of the primary chemicals at the Earth’s surface, and that the average composition of the overall system could be described. The composition of seawater, for example, was due to a series of reversible equilibrium reactions between the ocean waters, sediments and the atmosphere [6]. Similarly, it was proposed that the composition of the biosphere was determined by a complex series of equilibrium reactions – acid-base and oxidation-reduction reactions – by which the reduced volatile acids released from the depths of the Earth by volcanoes and other sources, reacted with the basic rocks of the Earth and with the oxygen in the atmosphere.

A follow-up paper in 1980 by McDuff and Morel [7] entitled The Geochemical Control of Seawater (Sillen Revisited), discussed in detail these approaches and contrasted them in terms of explaining the composition of the major ions in seawater. This paper focused on the controls over alkalinity in the ocean and the recycled source of carbon that is required to balance the removal of CaCO3 via precipitation in the ocean, and its burial in sediments. These authors concluded that “while seawater alkalinity is directly controlled by the formation of calcium carbonate as its major sedimentary sink, it is also controlled indirectly by carbonate metamorphism which buffers the CO2 content of the atmosphere” [7]. They concluded that the “ocean composition [is] dominated by geophysical rather than geochemical processes. The acid-base chemistry reflects, however, a fundamental control by heterogeneous chemical processes.”

McDuff and Morel [7] also focused attention on the importance of biological processes (photosynthesis and respiration) on the carbon balance, something that the earlier chemists did not consider [6]. These biological processes result in large fluxes via carbon fixation in the surface ocean and through organic matter degradation at depth, but overall most of this material is recycled within the ocean so that little organic carbon is removed from the system through sediment burial. Thus, the primary removal process for carbon is through burial of inorganic material, primarily as Ca and Mg carbonates. Recently, the short-term impact of increasing atmospheric CO2 on ocean chemistry has been vigorously debated, and is a topic of recent research focus [8, 9] because of the resultant impact of pH change due to higher dissolved CO2 in ocean waters on the formation of insoluble carbonate materials. Carbonate formation is either biotic (shell formation by phytoplankton and other organisms) or abiotic. Thus, there has been a transition from an initial conceptualization of the ocean and the biosphere in general, as a physical chemical system to one where the biogeochemical processes and cycles are all seen to be important in determining the overall composition. This is true for saline waters as well as large freshwaters, such as the Great Lakes of North America, and small freshwater ecosystems, and even more so for dynamic systems, such as rivers and the coastal zone [2, 4, 10].

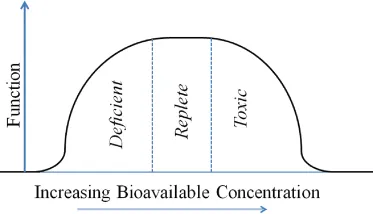

It has also become apparent that most chemical (mostly redox) reactions in the environment that are a source of energy are used by microorganisms for their biochemical survival and that, for example, much of the environmental oxidation and reduction reactions of Fe and Mn are mediated by microbes, even in environments that were previously deemed unsuitable for life, because of high temperature and/or acidity [2, 10]. Overall, microorganisms specifically, and biology in general, impact aquatic trace metal(loid) concentrations and fate and their presence and reactivity play multiple roles in the biogeochemistry of aquatic systems. Understanding their environmental concentration, reactivity, bioavailability and mobility are therefore of high importance to environmental scientists and managers. Trace metals are essential to life as they form the basis of many important biochemicals, such as enzymes [10, 11], but they are also toxic and can cause both human and environmental damage. As an example, it is known that mercury (Hg) is an element that is toxic to organisms and bioaccumulates into aquatic food chains, while the other elements in Group 12 of the periodic table – zinc (Zn) and cadmium (Cd) – can play a biochemical role [11]. Until recently, Cd was thought to be a toxic metal only but the demonstration of its substitution for Zn in the important enzyme, carbonic anhydrase, in marine phytoplankton has demonstrated one important tenet of the trace metal(loid)s – that while they may be essential elements for organisms, at high concentrations they can also be toxic [11, 12]. Copper (Cu) is another element that is both required for some enzymes but can also be toxic to aquatic organisms, especially cyanobacteria, at higher concentrations. This dichotomy is illustrated in Fig. 1.2, and is true not only for metals but for non-metals and organic compounds, many of which also show a requirement at low concentration and a toxicity at high exposure.

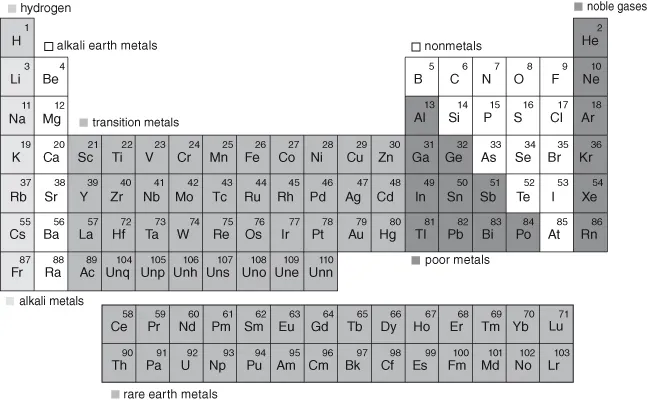

This dual role is also apparent for the group of elements, termed the metalloids, which occupy the bottom right region of the periodic table (Groups 13–17, from gallium (Ga) to astatine (As); see Fig. 1.3) [12]. They do not fit neatly into the definition of “trace metals,” as these elements are transitional between metals and non-metals in chemical character, but their behavior and importance to aquatic biogeochemistry argue for their inclusion in this book. Indeed, selenium (Se) is another example of an element that is essential to living organisms, being found in selenoproteins which have a vital biochemical role, but it can also be toxic if present at high concentrations [13]. As noted previously, the chemistry of both metals and microorganisms are strongly linked and many microbes can transform metals from a benign to a more toxic form, or vice versa; for example, bacteria convert inorganic Hg into a much more toxic and bioaccumulative methylmercury, while methylation of arsenic (As) leads to a less toxic product [14].

Therefore, in this book the term “trace metal(loid)” is used in a relatively expansive manner to encompass: (1) the transition metals, such as Fe and Mn, that are relatively abundant in the Earth’s crust but are found in solution at relatively low concentrations due to their insolubility, and because they play an important role in biogeochemical cycles [2, 10]; (2) the so-called “heavy metals,” such as Hg, Cd, lead (Pb) and Zn that are often the source of environmental concern, although some can have a biochemical role [4, 10]; (3) the metalloids, such as As and Se, which can be toxic and/or required elements in organisms; and (4) includes the lanthanides and actinides, which exist at low concentration and/or are radioactive [15]. Many of the lanthanides (so-called “rare earth elements”) are now being actively mined given their heighten...