Beer! This foamy, refreshing, sparkling alcoholic beverage conjures images of parties, festivals, sporting events, and generally fun stuff. Beer is as much a symbol of our culture as football or ballet.

1.1 Brief History

Beer Origins

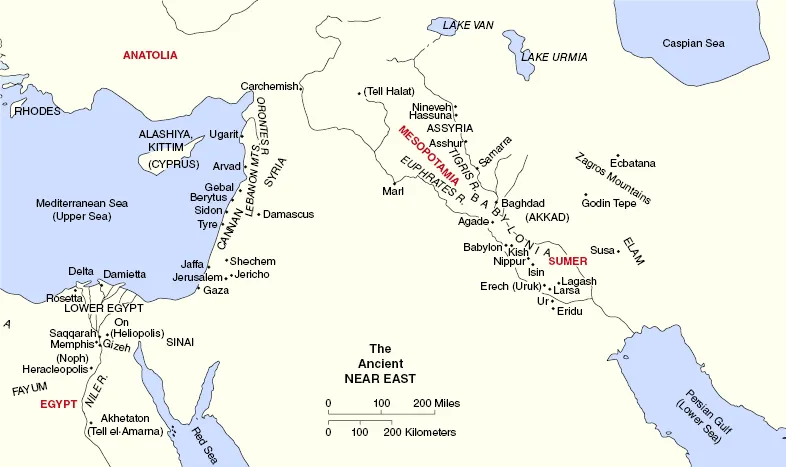

The origins of beer go back to the origins of civilization. Excavations at a prehistoric town, called Godin Tepe, located on the ancient Silk Road in the Zagros Mountains (Fig. 1.1) in what is now western Iran uncovered a 5500 year old pottery jar containing calcium oxalate (CaC2O4). Calcium oxalate is the signature of beer production. Although there is earlier evidence of mixed fermented beverages, the find at Godin Tepe is the earliest chemical evidence for the brewing of barley beer.

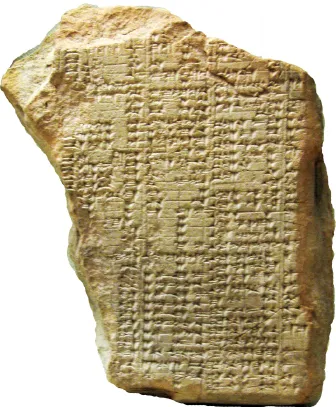

The history of beer is as old as history itself. History begins in Sumer (SOO mer), a civilization of city states in southeastern Mesopotamia (now Iraq) at the downstream end of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Sumer is the site of the first known written language. Sumerian and other Mesopotamian languages were written with symbols, called cuneiform, made with a wedge-shaped stylus often pressed into moist clay tablets. Clay is durable; many ancient cuneiform documents survive and have been translated. Among the earliest of these are documents written 5000 years ago concerning the brewing and consumption of beer (Fig. 1.2). These tablets record an already mature brewing culture, showing that beer was old when writing was new. One famous cuneiform tablet from 4000 years ago has a poem called Hymn to Ninkasi, a hymn of praise to the Sumerian goddess of beer. The Hymn has a poetic but not completely comprehensible account of how beer was made. The Sumerians made beer from bread and malt (or maybe malt bread), and flavored it, perhaps with honey. Sumerian documents mention beer frequently, especially in the context of temple supplies. Beer was also considered a suitable vehicle for administering medicinal herbs.

Babylon and Egypt

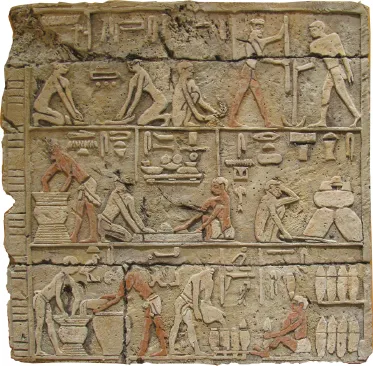

Dominance over the Mesopotamian region passed back and forth among the Sumerian cities until they were conquered by Hammurabi of Babylon 3700 years ago. Babylon was a city on the Euphrates upriver from Sumer. Beer made from barley or emmer (an ancient form of wheat) was a staple of the Babylonian diet. After Babylon came Assyria, ruling the Middle East from its two capitals of Assur and Nineva. The Assyrians were displaced by a second wave of Babylonians, among whom was Nebuchadnezzar of Biblical infamy. These cultures continued the brewing tradition of Sumer. It is believed that brewing spread from the Mesopotamian region to Egypt, about 800 miles (1300 kilometers) away in Africa. Beer was the primary beverage in Egypt at all levels from the Pharaoh to the peasants. The dead were buried with supplies of beer. Mourners of deceased nobles brought offerings of beer to shrines in their tombs. There are many pictures and sculptures depicting brewing in ancient Egypt (Fig. 1.3). Modern scholars disagree on what can be inferred from these images about the details of ancient Egyptian brewing methods.

Europe

Little is known about the introduction of beer to northern Europe. Historical records from northern Europe before the Middle Ages are incomplete or missing. The Neolithic village of Skara Brae in the Orkney Islands off Scotland has yielded what some interpret as evidence of beer brewing 3500–4000 years ago. Finds of possible brewing 3000 miles from Sumer with little in between suggest that Europeans may have invented brewing independently. The Old English epic Beowulf, which was written some time around 1000, is set in a heroic Danish culture whose warriors seal their loyalty to their king during elaborate feasting and drinking of beer and mead, an alcoholic beverage made from honey.

Monasteries

European monasteries played a key role in the development of modern beer. St. Benedict of Nursia (480–547) in Italy wrote a set of monastic rules providing for a daily ration of wine. Beer seems to have been permitted under the rules of St. Gildas (∼504–570) in monasteries in Britain and Ireland. St. Columban (∼559–615) may have been influenced by Gildas in providing beer for monks in monasteries he founded in France. The monastic customs came together when the synods in 816 and 817 at Aachen brought monasteries in most of Western Europe under a single set of rules. These rules provided that each monk would get a pint of beer or half a pint of wine a day. Monasteries ranged in size from 30 to as many as 400 monks with a similar number of servants and serfs. A monastery that served 150 pints of beer a day would need over 560 gallons (2100 liters) a month. The beer/wine ration assured that many monasteries outside of the grape growing regions would house large breweries. Monasteries served as guest houses for travelers and many sold beer to make extra income. In around 820 a detailed drawing was prepared for renovations of the Monastery of St. Gall in Switzerland. The plan shows three breweries, one near the monks' kitchen, one near the pilgrims' quarters, and one near the guest house. Although there is no indication that the three-brewery plan was actually realized, the St. Gall plan shows that brewing beer had become the norm for a northern European monastery. Starting perhaps in the middle 900s, some monasteries were able to maintain a beer monopoly by controlling the license to produce gruit, a mixture of herbs used to flavor beer. This practice waned by the fifteenth century, because hops replaced gruit in most regions.

Hops

The hop is a climbing plant whose flowers are used to flavor nearly all beer made today (Fig. 1.4). The first historical record of the use of hops in beer is in a list of rules for monks written in 822. The rules were written by the abbot Adalhard (751–827) for the Monastery of St. Peter and St. Stephen in Corbie, northern France. Adalhard also founded the Corvey Monastery in north central Germany; some sources get these two monasteries mixed up. Hopping of beer at nearby French monasteries in Fontenelle and St. Denis was recorded slightly later. Hops were not cultivated, but were gathered from the wild. The use of hops in beer spread slowly and irregularly throughout Europe. Early evidence of cultivation of hops dates from 859–875 at the Abbey of Freisingen in Bavaria, southern Germany.

The Hanseatic League was a confederacy of trading cities on the north coast of Europe from 1159 to the 1700s. The Hanse traded at North Sea and Baltic Sea ports from Britain to Russia. One of the major Hanse commodities was beer. In its unhopped form, beer spoils rapidly, making it unsuitable for long distance trading. Hops, in addition to providing a unique flavor to beer, also acts as a preservative. Beer made with hops can stay fresh for weeks or months. The use of hops made beer a transportable commodity, allowing the Hanseatic League to introduce hopped beer to a large region in northern Europe. None of this happened overnight. Powerful people were making good money on gruit, the flavoring used before hops. These people used their influence on taxation and regulation to resist the introduction of a competing flavoring. Added to this is the innate conservatism of people about their food and drink. Hopped beer started to appear in England in the late 1300s mostly for the use of resident foreigners, including officials of the Hanseatic League. Different brewers made unhopped beer, called “ale” and the hopped product, called “beer.” By the end of the 1600s all beer in England was hopped. Today we use “beer” as the general term and ale is contrasted to lager according to the fermentation temperature.

Commerce and Regulation

Starting in the later 1000s, commercial brewers began to set up shop in cities in what is now Belgium. Beer was an ideal product to tax because it was prepared in specialized facilities in batches of fixed size. While it might be possible to make a few pairs of shoes or rolls of wool under the table, it would have been difficult to conceal a batch of beer from the authorities. Beer taxation, both direct and indirect (as by taxing the ingredients), became an important source of revenue for various levels of government. Because of their financial interest in beer, governments got into the habit of regulating the ingredients, preparation, and sale of beer. In addition to taxation, other aspects of the brewing trade were of interest to the town government. Brewing requires heat, which in the Middle Ages meant fire. Breweries were subject to fires that, because of wooden construction, could spread to whole neighborhoods. In an effort to control fire risk, many towns had regulations on where breweries could be built and with what materials of construction. Brewing competes for grain with bread baking, which was seen as essential to feed the population. This may have been the motivation for the famous Reinheitsgebot (German: Reinheit, purity + gebot, order). This regulation, which permitted only barley, hops, and water in beer, was first issued in Munich in 1487. In 1516 the rule was extended to all of Bavaria (southern Germany). One effect of this regulation was a severe limitation on the import of beer into the regions in which it held sway. The Reinheitsgebot, in modified form, stayed in effect until it was set aside by the European Union in 1987. Even today it influences brewing practices all over the world.