![]()

CHAPTER 1

How to Retire at 36

I was not born into a wealthy family with rich relatives who buy winning lottery tickets, nor did I invent website destinations that make billions when they go public, and yet I retired at 36. Here is how I did it.

The story began when I walked into a bank, hand-in-hand with my mom, and deposited my life's savings—just over $100—which was the minimum needed before they paid interest.

Each time the bank updated my passbook, I had a warm feeling of accomplishment. The more I saved, the more they paid me to save, and that reinforced a belief system that endures to this day.

I received a massive raise in my weekly allowance from 60 cents to $7.60 when my father started a new job managing a large apartment complex. I became a garbage man, moving hundreds of smelly garbage bags from the collection room inside the buildings to the street. I saved almost every penny I earned.

Five days after I turned 16, I got my first job washing dishes at the Gould Hotel. I spent more than two years there, earning $2.05 an hour. That was a nickel above minimum wage, so I felt fortunate.

When my parents moved away, I stayed behind and spent the last five months of high school living out of a hotel room. I worked part time washing dishes and doing odd jobs for the hotel until I graduated. I paid a token amount for room and board under the kind generosity of the owner, George Bantuvanis, and starved on the weekends when the kitchen was closed. The money I saved went to pay for college, but saving money is a theme that runs throughout my early years.

I worked my way through college by pumping gas or doing temp agency jobs, such as running the mailroom for the summer at a brewery. Too bad I dislike beer.

Within the first year of graduating from college with a bachelor of science degree in computer engineering, I paid off my $600 student loan, repaid with interest the $1,000 “startup” funds my parents loaned me, and was debt free.

My first professional job was as a hardware design engineer at Raytheon, working on the Patriot air defense system. I arrived early and charted my favorite stocks on a piece of graph paper hung on the office wall. While I used strict fundamental analysis for my stock picks, my officemate, Bob Kelly, closed his eyes, twirled his hand around, and plunged it into the Wall Street Journal to make his choices.

I tracked my selections, his random picks, and after six months discovered two things: (1) he was beating me, and (2) I did not have a clue what I was doing. I continued paper trading using price to earnings and price to sales ratios as my main selection themes. I pored through Forbes and Fortune in the company library and learned to love fundamental analysis. Value investing was king!

In late 1980, the prime rate climbed to 21.5 percent and in 1982, the stock market became an airplane taking off on a journey to the clouds. I participated by putting my savings to work in a money market fund and dabbling in no load mutual funds with my retirement savings.

Four years after beginning paper trading, I opened a brokerage account. I had no choice. The company where I then worked as a software engineer had a stock purchase program in which I participated. At the end of the year, they gave me a stock certificate, and the easiest way to sell it was through a brokerage account.

The first stock I picked was Essex Chemical. I chose that one because I liked the fundamentals and because they frequently issued dividends in the form of cash and stock. I made 88 percent on that one. I chose Nuclear Pharmacy next mainly because of its way-cool name, but also with an eye toward the fundamentals. I found the company buried in a prospectus of a mutual fund I owned. Since I already owned it through the mutual fund, there should have been no reason to buy more, but I did. The stock dropped and Syncor International gobbled it up on the cheap, handing me a 25 percent loss.

However, the next several trades did well, climbing 195 percent (Carter-Wallace), 123 percent (another run at Essex Chemical), and 56 percent (Rite Aid) before encountering a string of losses: –41 percent (Dynascan), –39 percent (Intelligent Systems), and –30 percent (Key Pharmaceuticals).

After about a decade of using fundamental analysis and value investing, I grew tired of seeing a stock double or triple and then drop in half—or worse. I added technical analysis to prevent the large givebacks while still keeping my toe dipped in the fundamentals.

Then came my first big winner: Michaels Stores.

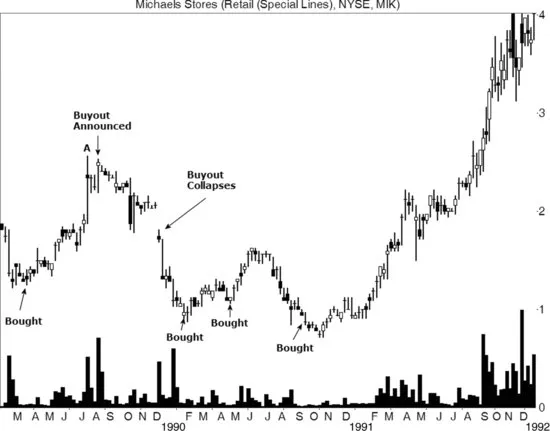

Figure 1.1 shows Michaels Stores on the weekly scale. Do not bother hunting for it in the grocery aisle. It no longer trades, and I will tell you why later.

The first buy, in March 1989, at a split-adjusted price of $1.28, happened just after it bottomed from a swift, one-day plunge of 26 percent in mid-February. Analysts call such plunges dead-cat bounces, and they will become routine for the stock (18 while I owned it). Price climbed in an accelerated fashion, spiking at point A. At the peak, I had doubled my money on paper (the high was $2.57).

Three weeks later came the announcement of a buyout of the company for (split-adjusted) $3.00 in cash and preferred stock in the acquirer. What I find unusual about the offer is the timing. It appears that the smart money was anticipating good news because of the run-up from the February 1989 low, especially the sharp move during the week ending at point A. Also unusual is what happened to price after the announcement: It eased lower. Typically, when a buyout occurs, price jumps up, and then flat-lines like a dead animal until the transaction completes. Was this a case of buy on the rumor and sell on the news? Perhaps.

The deal collapsed in early December when the buyer could not find financing for the deal. Price gapped 14 percent lower and continued sinking in a quicksand of falling prices, eventually hitting bedrock in late January at a low of 88 cents. From the close before the deal collapsed, the decline measured a tasty 57 percent. Instead of doubling my money at the peak, I was looking at a 31 percent loss. Buy and hold turned into buy and bust.

That is when I had one of those eureka moments. I remember thinking that if the stock was good enough for Robert Bass and his Arcadia Partners (one of the groups involved in the buyout), then it was good enough for me. I bought the stock again and again and again (with great timing, I might add) and look what happened. In late 1990, price started moving up. By 1992, the gain from my lowest purchase price (88 cents) was 369 percent higher.

I still saved my pennies and invested them in other stocks with good results, so when the company where I worked decided to spin off/sell their manufacturing operations and the layoffs came, I was ready. I opened my wallet and started counting. If I spent no more than $10,000 annually, I would be flat broke at 65. Retiring and doing what I wanted sounded a lot more appealing than working for others, so I hung up my keyboard and retired at 36.

When I say retired, I mean I had no earned income for years. I started trading stocks more often, writing articles, and then writing books while leaving plenty of playtime. I still think of myself as retired because I can do whatever I want every day, and that is exactly what I do.

Anyway, back to Michaels Stores. Over the years, I bought it 25 times. In eight of those trades, I more than doubled my money with my best gain coming from the stock I bought in 1990 at 88 cents. When the company went private in 2007, I sold it to them at $44 for a rise of almost 5,000 percent. On those shares, for every dollar invested, I made $50.

When you look at all of my trades throughout the years, I at least doubled my money on 32 of them. When you couple that with a lifestyle that says avoid the name brands because the store brands are just as good at a fraction of the cost, it all adds up to one thing: retiring at 36.

CHAPTER CHECKLIST

If you need a checklist for how to retire young, here is how I did it.

Work hard and save every penny you earn at a job that pays a good salary.

Live as cheaply as you can and invest your savings with care.

Find stocks in which a buyout collapses. Buy when they bottom.

Hold those stocks for the long term (I held some of Michaels Stores for 18 years).

Hope that they move up—a lot.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

Money Management

In movies you hear the phrase Follow the money, so money management is where our journey begins.

Are you like John? He daydreams of working two hours in the morning trading stocks and then catching some rays outside as he powers his bicycle over rolling hills or cruises around the lake in a rowboat, chasing geese. Instead, he is stuck working up to 12 hours a day at a dead-end job he once considered exciting. He opens his checkbook, looks at the balance, and then fires off an e-mail. “How much money do I need to start trading?”

That is a common question without a simple answer. Why? Because it depends on your circumstances. If Aunt LoadedMama left you millions, then you can probably scrape by. But if you are like me and do not have rich relatives or generous benefactors, then you have to depend on your own skills to feed the bank account. Acquiring that skill takes time.

Before going further, let us define terms.

- Buy-and-hold investor, or just investor, trades for...