![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

The search for new drugs is a long process. Attrition is high and the costs keep escalating (now perhaps as high as $2 billion per marketed drug). The traditional discovery–development models are undergoing change, as many pharmaceutical companies reign in the R&D costs, by consolidating research sites, downsizing research staff, engaging in more outside collaborations, and outsourcing.

1.1 BULLDOZER SEARCHING FOR A NEEDLE IN A HAYSTACK?

Although the last decade has led to improvements in attrition due to poor pharmacokinetic profiles of discovery compounds, drug absorption continues to be an important issue in modern pharmaceutical research and development. The search for new drugs is daunting, expensive, and highly risky, but potentially highly rewarding.

If chemicals were confined to molecular weights of less than 600 Da and consisted of common atoms, the chemistry space is estimated to contain 1040 to 10100 molecules, an impossibly large space to search for potential drugs [1]. To address this limitation of vastness, “maximal chemical diversity” [2] was applied in constructing large experimental screening libraries. It’s now widely accepted that the quality of leads is more important than the quantity. Traditionally, large compound libraries have been directed at biological “targets” to identify active molecules, with the hope that some of these “hits” may someday become drugs. The pre-genomic era target space was relatively small: Less than 500 targets had been used to discover the known drugs [3]. This number may expand to several thousand in the next few years as genomics-based technologies and better understanding of protein–protein interactions uncover new target opportunities [4, 5]. Of the estimated 3000 new targets, only about 20% are commercially exploited [5]. Due to unforeseen complexities of the genome and biologic systems, it is taking a lot longer and is more expensive to exploit the new opportunities than originally thought [5–8].

Although screening throughputs have massively increased over the past 20 years (at great cost in set up and run), lead discovery productivity has not necessarily increased accordingly [5–8]. C. Lipinski has suggested that maximal chemical diversity is an inefficient library design strategy, given the enormous size of the chemistry space, and especially that clinically useful drugs appear to exist as small tight clusters in chemistry space: “… one can make the argument that screening truly diverse libraries for drug activity is the fastest way for a company to go bankrupt because the screening yield will be so low” [1]. Hits are made in pharmaceutical companies, but this is because the most effective (not necessarily the largest) screening libraries are highly focused, to reflect the putative tight clustering. Looking for ways to reduce the number of tests, to make the screens “smarter,” has an enormous cost reduction implication.

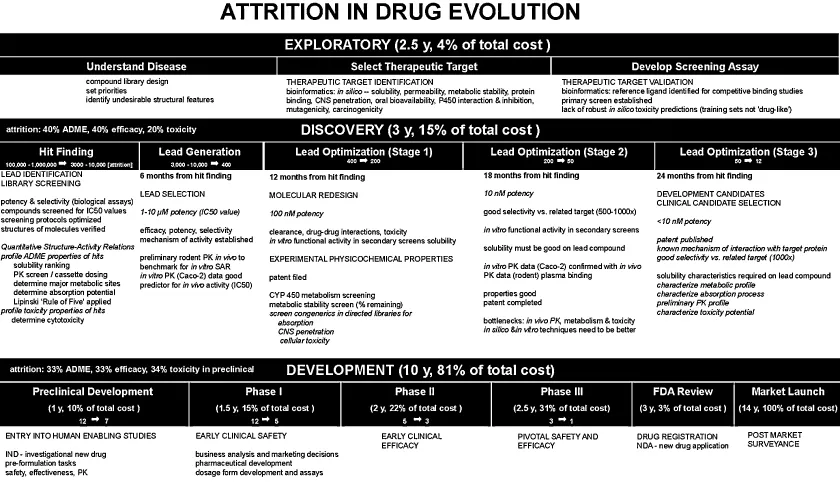

Figure 1.1 sketches out the process of drug exploration, discovery, and development followed at several pharmaceutical companies in the early 2000s [9–12]. A large pharmaceutical company may screen 100,000 to 1,000,000 molecules for biological activity each year. Some 3000–10,000 hits are made. Most of these molecules, however potent, do not have the right physicochemical, stability, and safety properties. Large pharmaceutical companies promote about 12 molecules into preclinical development each year. Only about 5 in 12 candidates survive after Phase I (Figure 1.1). A good year sees perhaps just one molecule reach the product stage after 9 molecules enter first-in-man clinical testing [6]. For that molecule, the start-to-finish may have taken 14 years (Figure 1.1).

The molecules that fail have “off-target” activity or poor side effects profiles. Unfortunately, animal models have been weak predictors of efficacy and/or safety in humans [7]. The adverse reactions in humans are sometimes not discovered until the drug is on the market in large-scale use in humans.

In 2001, a drug product cost about $880 million to bring out to market—which included the costs of numerous failures (Figure 1.1). In 2010, the cost was closer to $2 billion/approval [7]. It has been estimated that about 33% of the molecules that reach preclinical development are eventually rejected due to ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion) problems. Other attrition causes are lack of efficacy (33%) and toxicity (34%). Much more money is spent on compounds that fail than on those that succeed. The industry has started to respond by attempting to screen out those molecules with poor ADME properties during discovery, before the molecules reach development. However, that has led to another challenge: how to do the additional screening quickly enough [13]. An undesirable consequence of cheap and quick assays it that their quality is low [5].

Combinatorial chemistry programs have tended to select for higher-molecular-weight molecules, predictably low in solubility. “Early warning” tools, such as Lipinski’s “Rule of Five” [1] and simple computer programs that predict solubility and other properties from 2-D structure [14, 15], attempt to weed out such molecules early in discovery programs. Still, many solubility-problematic molecules remain unrecognized in early studies, due to the overly simplistic methods used to measure solubility in discovery [16]. More accurate (but still fast) solubility [16–19] (Chapter 6) and artificial membrane permeability [20–24] (Chapter 7) methods in the candidate selection stage in pharmaceutical R&D have proven to be particularly helpful for recognizing at a much earlier time the truly problematic molecules. It had even been suggested that screening for future formulation efficacy (pH and excipient effects on solubility and permeability) of candidates could be justified, if the methods were fast, compound-sparing, cost effective, and reasonably accurate [16, 18].

1.2 AS THE PARADIGM TURNS

As a consequence of the increased and unsustainable cost of bringing out a therapeutic product, many pharmaceutical companies have begun to change the way discovery and development are done [5]:

- Size and scope of internal research capabilities are decreasing, as more outsourcing is considered, not only in discovery, but also in development.

- Several companies have rearranged internal structures to be smaller “biotech-like” units.

- External collaborations with small biotech companies and academia have increased.

- Many in the industry predict that more biologic therapies will emerge (which have lower Phase II attrition [6]), and the emphasis on small molecules may decrease.

Strategies of discovery are changing [7]:

- Development of multitargeted therapeutics will increase.

- Whole pathway approaches, drawing on increasing understanding of protein–protein interactions, will be increasingly explored.

- Biology-driven drug discovery, starting with a specific disease model and a pathway, benefitting from external collaborations with academic groups.

- Analysis of multigenic complex diseases.

- Network pharmacology.

- Obtaining early proof of concepts, with small clinical studies and/or applying microdosing.

The “open innovation model” (OIM) [8] involves the progression of discovery and development that’s different from that depicted in Figure 1.1. An attrition “funnel” will start with many test compounds. Even at the early stage, ideas and technologies may be either in-licensed or out-licensed. At later optimization stages, two-way collaborations with academic labs will play an increasing role. Product in-licenses will be considered. Near the product launch stage, line extensions via partners and joint ventures will become increasingly popular. In the OIM, intellectual property would be selectively distributed and proactively managed and shared to create value that otherwise would not surface.

1.3 SCREEN FOR THE TARGET OR ADME FIRST?

Most commercial combinatorial libraries, some of which are very large and may be diverse, have a very small proportion of drug-like molecules [1]. Should only the small drug-like fraction be used to test against the targets? The existing practice is to screen for the receptor activity before “drug-likeness.” The reasoning is that structural features in molecules rejected for poor ADME properties may be critical to biological activity related to the target. It is believed that active molecules with liabilities can be modified later by medicinal chemists, with minimal compromise to potency. Lipinski [1] suggested that the order of testing may change in the near future, for economic reasons. He adds that looking at data already available from previous successes and failures may help to derive a set of guidelines to apply to new compounds. When a truly new biological therapeutic target is examined, nothing may be known about the structural requirements for ligand binding to the target. Screening may start as more or less a random process. A library of compounds is tested for activity. Then computational models are constructed based on the results, and the process is repeated with newly synthesized molecules, perhaps many times, before adequately promising compounds are revealed. With large numbers of molecules, the process can be costly. If the company’s library is first screened for ADME properties, that screening is done only once. The same molecules may be recycled against existing or future targets many times, with knowledge of drug-likeness to fine-tune the optimization process. If some of the molecules with very poor ADME properties are judiciously filtered out, the biological activity testing process would be less costly. But the order of testing (activity versus ADME) is likely to continue to be the subject of future debates [1].

1.4 ADME AND MULTIMECHANISM SCREENS

In silico property prediction is needed more than ever to cope with the screening overload [14, 15]. Improved prediction technologies are continuing to emerge. However, reliably measured physicochemical properties to use as “training sets” for new target applications have not kept pace with the in silico methodologies.

Prediction of ADME properties should be simple, since the number of descriptors underlying the properties is relatively small, compared to the number associated with effective drug-receptor binding space. In fact, prediction of ADME is difficult. The current ADME experimental data reflects a multiplicity of mechanisms, making prediction uncertain. Screening systems for biological activity are typically single mechanisms, where computational models are easier to develop [1].

For example, aqueous solubility is a multimechanism system. It is affected by lipophilicity, H-bonding between solute and solvent, intra- and intermolecular H-bonding, electrostatic bonding (crystal lattice forces), and charge state of the molecule. When the molecule is charged, the counterions in solution may affect the measured solubility of the compound. Solution microequilibria occur in parallel, affecting the solubility. Many of these physicochemical factors are not well understood by medicinal chemists, who are charged with making new molecules that overcome ADME liabilities without losing potency.

Another example of a multimechanistic probe is the Caco-2 permeability assay (Chapter 8). Molecules can be transported across the Caco-2 monolayer by several mechanisms operating simultaneously, but to varying degrees: transcellular passive diffusion, paracellular passive diffusion, lateral passive diffusion, active influx or/and efflux mediated by transporters, passive transport mediated by membrane-bound proteins, receptor-mediated endocytosis, pH-gradient- and electrostatic-gradient-driven mechanisms, and so on (Chapter 2). The P-glycoprotein (Pgp) efflux transporter can be saturated if the solute concentration is high enough during the assay. If the substance concentration is very low (perhaps because not enough of the compound is available during discovery, or due to low solubility), the importance of efflux transporters in gastrointestinal tract (GIT) absorption can be overestimated, providing the medicinal chemist with an overly pessimistic prediction of intestinal permeability [1, 25]. Drug metabolism in some in vitro cellular systems can further complicate the assay outcome.

Compounds from traditional drug space (“common drugs”—readily available from chemical suppliers), often chosen for studies by academic laboratories for assay validation and computational model-building purposes, can lead to misleading conclusions when the results of such models are applied to “real” [12] discovery compounds, which most often have extremely low solubilities [25].

Computational models for single-mechanism a...