1

Properties and Use of Microreactors

1.1 Introduction

Microreactors are devices that incorporate at least one three-dimensional duct, with one or more lateral dimensions of <1 mm (typically a few hundred micrometers in diameter), in which chemical reactions take place, usually under liquid-flowing conditions [1]. Such ducts are frequently referred to as microchannels, usually transporting liquids, vapors, and/or gases, sometimes with suspensions of particulate matter, such as catalysts (Figure 1.1) [2]. Often, microreactors are constructed as planar devices, often employing fabrication processes similar to those used in manufacturing of microelectronic and micromechanical chips, with ducts or channels machined into a planar surface (Figure 1.2c and d) [3]. The volume output per unit time from a single microreactor element (Figure 1.2b, c, d and e) is small, but industrial rates can be realized by having many microreactors working in parallel (Figure 1.2f).

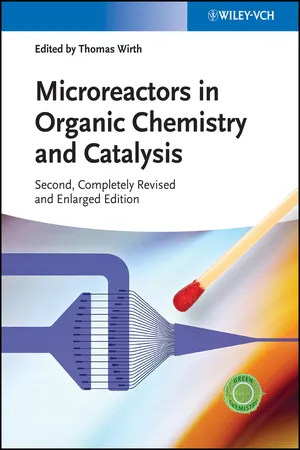

Figure 1.1 Detailed example of a simple duct-based microreactor fabricated from polytetrafluoroethylene (with perfluoralkoxy capping layer). Reagents 1 and 2 interact by diffusive mixing within the reaction coil. The reaction product becomes the continuous phase for an immiscible discontinuous phase, which initially forms elongate slugs. When subject to a capillary dimensional expansion, slugs become spheres, which are then coated with a reagent (that is miscible with the continuous phase) fed through numerous narrow, high aspect ratio ducts made with a femtosecond laser.

Figure 1.2 Examples of modern-day microreactors and other microfluidic components. (a) Source: Reprinted with permission from Takeshi et al. (2006) Org. Process Res. Dev., 10, 1126–1131. Copyright (2006) American Chemical Society.

However, microreactor research can be conducted on simple microbore tubing fabricated from stainless steel (Figure 1.2a), polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), or any material compatible with the chemical processing conditions employed [4]. For instance, inexpensive fluoroelastomeric tubing was employed to prepare a packed-bed microreactor for the catalysis of oxidized primary and secondary alcohols [5]. As such, microreactor technology is related to the much wider field of microfluidics, which involves an extended set of microdevices and device integration strategies for fluid and particle manipulation [6].

1.1.1 A Brief History of Microreactors

In 1883, Reynolds' study on fluid flow was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society [7]. Reynolds used streams of colored water in glass piping to visually observe fluid flow over a range of parameters. The apparatus used is depicted in a drawing by Reynolds himself (Figure 1.3), which shows flared glass tubing within a water-filled tank. Using this setup, he discovered that varying velocities, diameters of the piping, and temperatures led to transitions between “streamline” and “sinuous” flow (respectively known as laminar and turbulent flow today). This paper was a landmark, which demonstrated practical and philosophical aspects of fluid mechanics that are still endorsed and used in many fields of science and engineering today, including microreactor technology [8].

Figure 1.3 The original apparatus used by Osborne Reynolds to study the motion of water [7]. The apparatus consisted of a tank filled with water and glass tubing within. Colored water was injected through the glass tubing, so the characteristics of fluid flow could be observed.

An early example for the use of a microreactor was demonstrated in 1977 by the inventor Bollet, working for Elf Union (now part of Total) [9]. The invention involved mixing of two liquids in a micromachined device. In 1989, a microreactor that aimed at reducing the cost of large heat release reactions was designed by Schmid and Caesar working for Messerschmitt–Bölkow–Blohm GmbH. Subsequently, an application for patent was made by the company in 1991 [10]. In 1993, Benson and Ponson published their important paper on how miniature chemical processing plants could redistribute and decentralize production to customer locations [11]. Later, in 1996, Alan Bard filed a US patent (priority 1994) where it is taught how an integrated chemical synthesizer could be constructed from a number of microliter-capacity microreactor modules, most preferably in a chip-like format, which can be used together, or interchangeably, on a motherboard (like electronic chips), and based upon thermal, electrochemical, photochemical, and pressurized principles [12]. Following this, a pioneering experiment conducted by Salimi-Moosavi and colleagues (1997) introduced one of the first examples of electrically driven solvent flow in a microreactor used for organic synthesis. An electro-osmotic-controlled flow was used to regulate mixing of reagents, p-nitrobenzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate (AZO) and N,N-di-methylaniline, to produce a red dye [13]. One of the first microreactor-based manufacturing systems was designed and commissioned by CPC in 2001 for Clariant [14].

Microreactor systems have since evolved from basic, single-step chemical reactions to more complicated multistep processes. Belder et al. (2006) claim to have made the first example of a microreactor that integrated synthesis, separation, and analysis on a single device [15]. The microfluidic chip fabricated from fused silica (as seen in Figure 1.4) was used to apply microchip electrophoresis to test the enantioselective biocatalysts that were created. The authors reported a separation of enantiomers within 90 s, highlighting the high throughput of such devices.

Figure 1.4 Fused silica microfluidic chip compared to the size of a €2 coin. The chip was the first example of synthesis, separation and analysis combined on a single device. Source: Photograph courtesy of Professor D. Belder with permission.

Early patents in microreactor engineering have been extensively reviewed by Hessel et al. (2008) [16] and then later by Kumar et al. (2011) [17]. From 1999 to 2009, the number of research articles published on microreactor technology rose from 61 to 325 per annum (Figure 1.5a) [17]. The United States of America produced the majority of research articles, followed by the People's Republic of China and Germany (Figure 1.5c) [17]. The number of patent publications produced was also highest in the United States of America; the data are given in Figure 1.5b [17]. The number of patent publications is highest in the field of inorganic chemistry, but of particular interest, organic chemistry comes second out 18 fields of chemical applications investigated [16].

Figure 1.5 (a) The number of research articles published on microreactors from the years 1999 to 2009. (b) Distribution of patent publications produced from 10 different countries. (EP: European; US: United States; DE: Germany; JP: Japan; GB: United Kingdom; FR: France; NL: Netherlands; CH: Switzerland; SE: Sweden). (c) Distribution of published research articles from various countries. Source: Images reprinted from Ref. [17], with permission from Elsevier.

Microreactor technology has been widely employed in academia and is also beginning to be used in industry where clear benefits arise and are worthy of new financial investment. Companies contributing considerably to the development of microreactors include Merck Patent GmbH, Battelle Memorial Institute, Velocys Inc., Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe, The Institute for Microtechnology Mainz, Chemical Process Systems, Little Things Factory GmbH, Syrris Ltd, Ehrfeld Mikrotechnik BTC, Micronit BV, Mikroglas chemtech GmbH, Chemtrix BV, Vapourtec Ltd, Microreactor Tec...