![]()

1

System Engineering

Give a man a fish, feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, feed him for a lifetime.

Chapter Organization

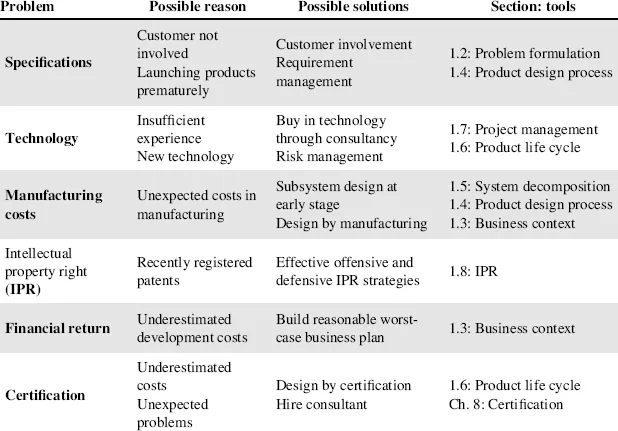

Less than one-third of medical device development projects succeed in getting to the marketing stage (Kelleher, 2003). Table 1.1 adapted from (Kelleher, 2003) summarizes the main reasons for failure in medical device development. Certification is also added as a possible critical issue since it is a significant barrier especially for new companies (CB, 2004; Anast, 2001; EEC, 2007).

Table 1.1 Problems, solutions and tools in medical design.

The application of engineering methods and processes may significantly reduce the risk of failures from the problems in Table 1.1. With this in mind, the theory part of this chapter introduces main engineering approaches here defined as ‘tools’ described in the sections indicated in the final column of Table 1.1. These widely used tools are described here and applied to the design and development of medical instruments.

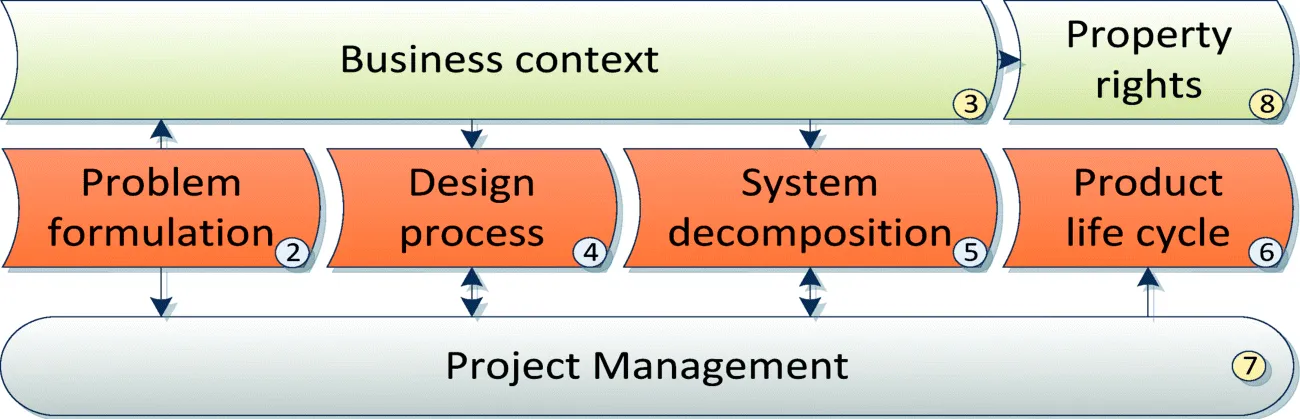

The tools and the corresponding paragraphs are introduced in a logical sequence as shown in Figure 1.1, where blocks represent sections indicated in the circled number. The main stream of product design starts from problem formulation (Section 1.2) to the product life cycle (Section 1.6). Any unique temporary activity such as design can be considered as a project that require specific management (Section 1.7). During and after design, intellectual property right (IPR) has to be faced with care to avoid infringing existing patents and to eventually protect the own product innovation as discussed in 1.8.

The implementation part of this chapter applies theory to a medical instrument example: the electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG). This book fully discloses a commercially available ECG product: the Gamma Cardio CG (CGV model) from the Gamma Cardio Soft company. The product's details are used to explain how theoretical concepts are translated into real marketable medical instruments. The implementation describes the ‘know-how’ of design and the ‘know-why’ of design decisions and rationales. The know-why has a general validity beyond ECG, since the rationale is common to medical devices generally. This design-oriented approach is useful in understanding the main concepts related to physiology, the principles underlying medical instruments and the applications of these instruments.

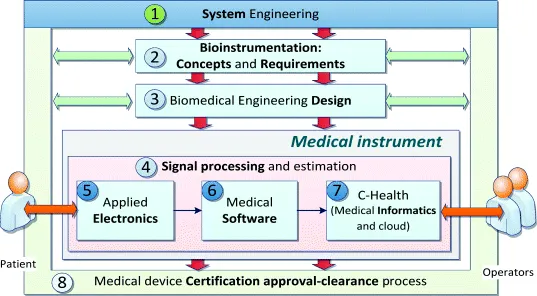

The book organization follows the design process as outlined in Figure 1.2. Chapter 1 addresses the tools required to design electronic products applying the concepts to medical instrumentation. The development process starts with product concepts and requirements (Chapter 2) that feed the design stage (Chapter 3). Signal processing and estimation is pervasive in all the conceptual blocks of a medical instrument. Chapter 4 introduces the mathematical framework required to handle signals and to assess performance through the whole medical system including electronics (Chapter 5), software (Chapter 6) and telecommunications/ICT components such as the e-Health products. Advances in medical device technology are increasing the need for alternative, simpler solutions for accessing and sharing medical data and services. Cloud computing is gaining prominence as a technological solution for distributing medical solutions. This issue is addressed in Chapter 7, where we introduce the new term ‘C-Health’ referring to ‘the set of healthcare services supported by cloud computing’. Chapter 8 covers medical instrumentation approval by regulatory bodies referred to as certification, clearance or other terms, according to specific authority.

Part I: Theory

1.1 Introduction

This chapter outlines the engineering tools and methodologies that are introduced in a logical order. Referring to Figure 1.1, design is first a problem that has to be formulated (Section 1.2). A systematic approach to describing a problem helps greatly in solving the problem itself. The business context (Section 1.3) has to be assessed at all the design stages to avoid technology-driven market failures. Design has to be performed in a systematic process. In Section 1.4, a simplified model of product design is introduced. This model is similar to the problem solving processes used in many other applications.

Any design of non-trivial devices has a high level of complexity given by the wide set of design details that have to be addressed and solved coherently. Unfortunately, the human mind is only able to cope with a very limited problem size at one time, with limited details. Techniques for reducing and decomposing complexity are therefore compulsory for non-trivial product design. So, Section 1.5 introduces the system-subsystem decomposition techniques used in software and in general at system level.

Product development implies a life cycle process that encompasses the various steps required for creating new products (plan, analysis, design etc.). These steps can be structured using various approaches to suit the specific constraints, the features of the product and the context, as discussed in Section 1.6. The design of a medical product is a typical project activity and therefore it is worth analyzing major aspects and risks in managing projects (Section 1.7). Finally, during and after design, intellectual property rights (IPR) have to be faced with care to avoid infringing existing patents and to eventually protect the developers' own product innovation (1.8).

1.2 Problem Formulation in Product Design

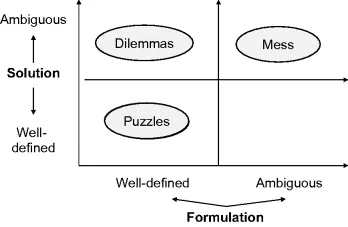

Product design is first a problem to be defined and solved. It is therefore worth focusing on the main aspects of problem solving and in particular on problem classification based on its formulation and solutions (see Figure 1.3). Problem formulation is the set of inputs and constraints available for problem solution. Effective formulation is critical to the outcome, especially considering that problems are usually ill-defined, multidimensional and with a wide constraining context. Effective formulation often requires an iterative approach: ‘First find out what the question is – then find out what the real question is.’ (Vince Roske)

Problem classification based on the characteristics of the input formulation and on the solution helps in analyzing the problem characteristics and results in more effective problem-solving strategies. Problems may be divided into puzzles, dilemmas and messes (Pidd, 2002). Problems given to students are usually just ‘puzzles’ because both formulations and solutions are well defined. At the other extreme, product design is usually a ‘messy’ or ‘wicked’ problem: there are many different ambiguous solutions based on tradeoffs, and formulation is usually ill-defined. Often, requirements become clear only when the problem (e.g., the design project) is close to being finished.

In these messy problems, the traditional step-by-step logic useful for solving puzzles may not be sufficient, but here other techniques such as ‘abstraction’ and ‘divide and conquer’ may help.

In product design, a simplified model of the product is derived through abstraction. From this first model, other more detailed models are derived, each getting closed to the real system to be implemented. This technique is exploited also for system-subsystem decomposition (Section 1.5) using the ‘divide and conquer’ technique. In this paradigm, a complex problem can be faced when it is broken down into smaller solvable components.

A systematic approach to defining a problem helps greatly in solving the problem itself:

‘If I had only one hour to save the world, I would spend fifty-five minutes defining the problem, and only five minutes finding the solution.’ (Albert Einstein).

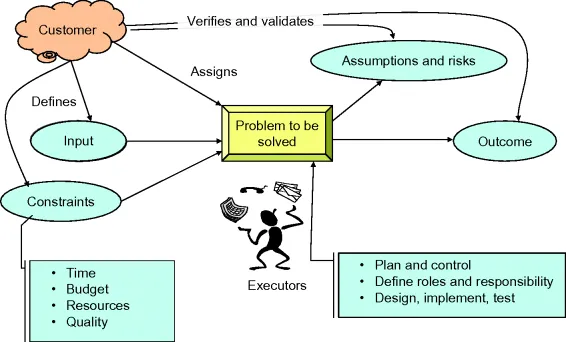

In a simplified approach, problem management may be schematized as depicted in Figure 1.4. A customer assigns to the executors a problem to be solved with a clear goal. The customer then identifies the output to be delivered when problem is solved.

The customer itself usually defines the input and con...