- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

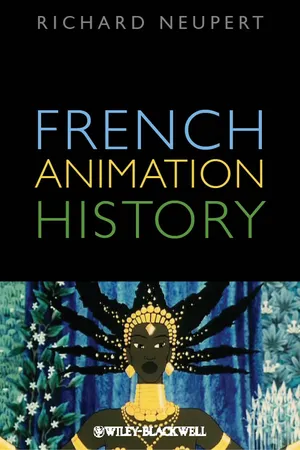

French Animation History

About this book

French Animation History is essential reading for anyone interested in the history of animation, illuminating the exceptional place France holds within that history.

- Selected by Choice as an Outstanding Academic Title for 2011

- The first book dedicated exclusively to this history

- Explores how French animators have forged their own visual styles, narrative modes, and technological innovations to construct a distinct national style, while avoiding the clichés and conventions of Hollywood's commercial cartoons

- Includes more than 80 color and black and white images from the most influential films, from early silent animation to the recent internationally renowned Persepolis

- Essential reading for anyone interested in the study of French film

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access French Animation History by Richard Neupert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

The Rise of Animation in France

If cinema marvelously expresses an age dominated by science, it is because cinema is “scientifically founded on movement.” In effect, cinema relies upon a series of mechanisms designed to produce an illusion of animation. (Guido 2007: 28)

Images remained fixed for 32,000 years. Drawings could only move once the camera was invented and put to work reproducing them 24 times a second, filming and projecting them. That is the real cinematic revolution! Animation is a completely virtual art which logically leads into the synthetic image and the modern world. The modern revolution was born with Emile Reynaud and his projected animation in 1892. Live action cinema with actors is merely a pale copy of reality. It is moving photography. … But the moving photograph will never be as magical as the moving drawing! (René Laloux, in Blin 2004: 148)

From the very beginning there was great potential for animation in France. Importantly, the French had built up strong traditions in the visual and graphic arts, scientific inquiry, and theatrical spectacles during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Artists from around the world came to Paris to study the fine arts and decorative arts, leading to one of the richest eras for aesthetic experimentation across the media. A number of avant-garde artists, including Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Fernand Léger, were drawn toward experimenting with the representation of time and motion and became fascinated with animated cinema's potential. It is true that France never possessed large specialized commercial animation studios during the silent or classical sound eras. Nonetheless, French animation has always existed and its animators have managed to turn out some incredibly creative and influential animation over the years. The bulk of that work has been produced by a relatively limited number of small animation firms and individual animators, often working parallel to other modern artists, exploring their media and looking for unique aesthetic approaches to animating images. Until fairly recently, animation remained on the economic periphery of French film production. French animation has also suffered from film critics and historians who have concentrated almost exclusively on France's famed avant-garde movements and narrative auteurism. Yet the history of animation is essential for understanding French film culture, its history, and its reception. Fortunately, there has been something of a renaissance in animation production within France over the past 20 years, which has motivated new interest in the long and, and as we shall see, frequently torturous history of French cartoons.

Animation has always been a more highly visible component of American film production than in France, and Hollywood cartoons have also received much more attention from film studies over the years. American animation began with a wide range of styles, techniques, and subjects during the silent era, much like in France. But American animation quickly became standardized as cartoons shifted from ink on paper to clear cels over painted backdrops. In Hollywood, animation fell into step with many conventions of live action filmmaking. By the 1930s, some major studios, including Warner Bros. and MGM, established their own animation wings while others, such as RKO and Paramount, entered into production and distribution deals with specialized animation companies like Disney and Fleischer. Hollywood's cartoon industry was built around division of labor, recurring characters and cartoon series, fixed durations of 6 to 8 minutes. American cartoons also received guaranteed distribution and thus predictable income. Most animation was commercially viable and highly capitalized. While there was creative differentiation from studio to studio, the output remained relatively similar, as even the series titles such as Merry Melodies and Looney Tunes (Warners), Silly Symphonies (Disney), and Happy Harmonies (MGM), suggest. Further, since the cartoons were produced under the institutionalized conditions of classical Hollywood cinema, they were also subject to regulation by the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association, which included censorship at the hands of the Production Code Administration. Cartoons were a very stable, successful, family friendly component of the American film industry.

By contrast, French animators worked more independently, like their colleagues in the plastic arts, or they formed small firms to create short animated motion picture commercials to be shown before the regular shows in theaters. These advertising contracts could ideally provide regular income and help bankroll more personal sorts of animated films on the side. Yet, as we shall see, animation remained a fragile cottage industry in France, an artisanal practice produced by individual auteurs or very small teams of animators. Although France was home to the world's first large movie studios, Pathé and Gaumont, animation was never a large part of their output. By the 1920s and 1930s, Pathé and Gaumont were primarily distributing independent and foreign films, including American cartoons. They did not have any sort of in-house animation unit during the years of classical cinema. Unlike Disney's animators or directors such as Chuck Jones and Tex Avery at Warner Bros., French animators never had access to long-term contracts, crews of assistants and in-betweeners, professional music and sound effects departments, or staff camera operators to compile and photograph their work. In France, animation teams were small and necessarily self-sufficient, working within an art cinema mode of production. The result is a fascinating cluster of films by individual stylists struggling to survive on the margins of a national film industry that was not really built to support their productions. Despite those conditions and challenges, the contributions of French animation have managed to be strong and varied over the past 120 years. Moreover, even before the first movies by Louis Lumière in 1895, France proved instrumental to the rise of animation and the representation of movement.

Motion picture animation fully exploits the potential of the cinematic apparatus, from camera to lab to projector. Thus, it seems valuable to situate cartoons at the very heart of cinematic technology and practice, rather than treating them as some marginal side-show or second-tier subset of national cinema. French Animation History investigates the rise and development of French animation, chronicles the norms and conventions of particular animators and their small, niche studios, and tests how story structures, graphic style, and sound strategies have shifted across time. Importantly, French animation exploits a wide range of techniques, some of which, from the earliest modes of animated pictures to the most contemporary computer generated and motion capture technology, even defy narrow definitions of animated cinema. While there is some reference here to television and other media, this study remains focused on cinema, helping situate animation as a vibrant, essential facet of film studies. France has also been a major player in exploring and exploiting new technologies. With the advances in computer generated imaging and digital compositing, the distinction “live action/not live” becomes less functional every day with each new development, further shifting various forms of animation to the core of film production today (Denslow 1997: 2). But even from the very earliest forms of motion devices, animation was a fundamental component for the successful recording and projection of moving images.

The Beginnings of Animation

Explanations of the origins of animation typically do not differ much from summaries of the origins of cinema itself. Survey histories often begin by mentioning cave paintings, magic lantern shows, and nineteenth-century motion devices. For many, when Ice Age's (Wedge, Saldanha, 2002) wooly mammoth Manfred wanders into a cave only to discover primitive sketches of men killing his ancestors, it is a poignant self-referential acknowledgment of modern animation's place in the history of humanity's deep-seated desire to represent movement. Paul Wells agrees that animation, in one form or another, has almost always been with us and cites Lucretius as describing a mechanism for projecting hand-drawn images onto a screen as early as 70 bc (Wells 1998: 11). Much later, optics and magic lantern shows during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were often initiated by scientists but adapted for public presentations of various sorts of lectures and entertainment spectacles. Some historians even argue that once the magic lantern was mass produced in the 1800s, it became “the first medium to contest the printed word as a primary mode of information and instruction” (Gunning 2000: xxvii). Certainly, by the nineteenth century, when the illusion of motion became quite common thanks to a wide variety of toys, scientific devices, and serial photography experiments, there were many amusements and businesses devoted to replicating movement, rather than just presenting series of images.

Paris, along with London, Berlin, and Brussels, was among the cities boasting networks of important scientists specializing in experiments involving the capturing of fixed images and replication of motion. One of the earliest instruments was the spinning thaumatrope, which might have a drawing of an empty bird cage on one side, and a painted bird on the other. When the device is spun around fast enough, the viewer's perception joins the two images and a relatively convincing image of a bird in a cage results. This apparatus was initially made available commercially thanks to Dr. John A. Paris in England in the 1820s. Peter Mark Roget and Belgium's Joseph Plateau were also researching “persistence of vision” during this era, continuing a long line of scientific inquiry into measuring how briefly image impressions may remain on the human eye and still be legible. Plateau's phenakistoscope, patented in 1833, allowed more stable illusions via two discs: one static disc had a slit for looking at the second spinning disc, which featured a series of up to 20 images or “phases of action” arranged around its surface. The phenakistoscope, like many early optical toy attractions, is based on circularity and repetition, and its functions are ultimately limited by the small number of images on a disk (Dulac and Gaudreault 2006: 230).

One scholar of early motion devices, David Robinson, states confidently that Joseph Plateau was the first true animator: “Plateau had devised the earliest form of moving picture” (Robinson 1991: 8). French animator Emile Cohl acknowledges Plateau's significance: “Without animation we perhaps never would have had that incomparable invention, Lumière's cinématographe. … Most of us owned a phenakistoscope … the cinema is right there” (Cohl 2007: 301). A confederation of Belgian scholars concurs: “The cinema was born in Belgium. The animated film was as well since its inventors are Joseph Plateau with his phenakistoscope and the painter Madou who drew the images onto the cut wheels that made the device work” (Sotiaux 1982: 8). As many historians will warn, declaring a “first” anything is often a risky venture. Further, even defining what might qualify as the earliest instance of animation, much less cinema, is still hotly debated. Some might productively argue that spinning discs such as the phenakistoscope function as their own “screen” and thereby qualify as animated cinema, before the fact. It proves more functional, however, to designate such early modes as “animated pictures,” as in the case of a flip book, thaumatrope, and phenakistoscope, and “animated photographs” for looping devices exploiting serial photography, while reserving “animated cinema” for devices that exploit projection and/or a screen as part of their illusion of movement (the terms “animated pictures” and “animated photographs” are also employed by Dulac and Gaudreault 2006: 227–244). For our purposes, it seems valuable to investigate briefly several significant figures operating before the launch of Edison and Lumière's recorded live action films of the 1890s, since part of Robinson's important point is that cinema's first cartoons develop from techniques already pioneered and exploited in optical illusions, photographic processes, and projected spectacles that had become so important internationally during the 1800s.

The zoetrope, also known as “the Wheel of Life,” was much like the phenakistoscope, though it functioned thanks to a series of small images on a band of paper, rather than a spinning disc. While not specific to France, zoetropes were manufactured there and became quite popular. During the 1860s and 1870s, one could buy assorted sets of images, arranged in bands, much like comic strips, for zoetropes. Among the available subjects are such illustrative titles as “The Rising Moon,” “The Indian Juggler,” and “Fly! Leave my nose alone.” “The French Revolution” involves heads rolling off bodies, while others exploit abstract visuals. Further, image discs for the bottom of the zoetrope could also be purchased, such as the visually stunning but unsettling “Man Eater,” in which a small black figure seems to be flung by centrifugal force into a happy tiger's mouth (for more titles and illustrations, see Robinson 1991: figs. 31–46). Hence a zoetrope could actually have two separate animated cycles going every time it was spun, with the primary series of images on the inside drum and a rotating design or sequence at the bottom. The strip on the inside of the drum provided a horizontal circularity that allowed a minimally narrative “linearization of the action performed by the subjects depicted” (Dulac and Gaudrault 2006: 235), while the bottom disc recalled the radial arrangement of the phenakistoscope. The repetition of a limited number of images in this and other optical toys is in many ways typical of recent computer animation programs such as Flash, exploited so relentlessly by Internet web-page ads in particular. We should see a direct connection between the images that represent a monkey continually running back and forth across the top of an Internet site and the often spellbinding nineteenth-century motion devices of girls eternally jumping rope, horses leaping, or couples waltzing in circles.

Importantly, during the 1860s and 1870s, a variety of devices were developed to allow for the projection of zoetrope bands and other photographic images. The major French figure during this era of early animation devices was Emile Reynaud (1844–1918). In his teens, Reynaud had been an apprentice in mechanical engineering for precision machinery, where he learned to work on optical and scientific instruments. He pursued industrial design but also studied photography with Adam Salomon and learned magic lantern skills from a famous Catholic scientist and educator of the era, Abbé Moigno, also known as “the apostle of projection” (Mannoni 2000: 365). A popular scientist, subscribing to La Nature, the influential journal devoted to scientific applications for the arts and industry, Reynaud became frustrated with the poor image and color quality in the zoetrope and other optical devices, so he designed a superior alternative, the praxinoscope, which was patented in 1877. A series of 12 drawn images, color lithographs, on a flexible strip of paper was placed within a cylinder. In the center, a rotating “cage” of mirrors reflected the surrounding images as they passed by. The entire device looks a bit like a toy merry-go-round. Viewers looked directly at the sequence of stable images momentarily reflected on a mirror's face, rather than through slits. A candle in the middle could provide extra light for crisp resolution. During 1878, Reynaud marketed his praxinoscopes, along with packets of replaceable strips of images which typically involved subjects such as jugglers, animal tricks, or cavorting children. One series was even called “Baby's Lunch,” predating Lumière's famous film by nearly two decades. In the more elaborate “theater” versions sold in folding wooden boxes, a small rectangular peep hole provided the viewer a perfect vantage point onto the reflected series of images framed by drawn sets, creating a child's replica of a small theatrical stage.

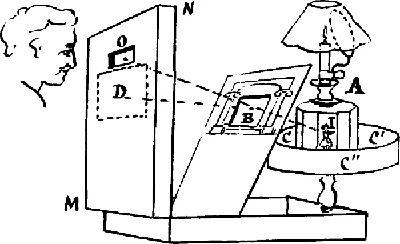

Figure 1.1 Praxinoscope patent, Emile Reynaud, 1878.

By 1879 Reynaud was producing a variation, the praxinoscope-théâtre, which printed isolated, colorful characters on the strips. An additional mirror allowed the viewer to project a background into the scene, so, for instance, a juggler could be seen in an interior room setting or outdoors in a garden. This was an early form of composite animation and delivered a new sense of depth to the presentations. Reynaud claimed eventually to have sold 100,000 praxinoscopes, which appeared in various models over the years, including one that was driven by an electric motor.

During the early 1880s Reynaud also experimented with projecting the drums of spinning images. When he presented a new projecting model of the praxinoscope to the Société Française de Photographie in 1880, for instance, he explained that the ideal goal would be for someone to invent a way to project photographic images for a better illusion of movement than drawn figures could generate (Mannoni 2000: 374). Reynaud's early prototype projector used 12 glass slides strapped together into a flexible belt of images for projection. This device also involved combining the moving figures from the glass slides with painted static backgrounds. They were both reflected onto the same mirror during projection for the composite image. But clearly Reynaud saw the continued limitations of his short series of hand-drawn images printed on slides. In 1888, Reynaud patented an important variation on the praxinoscope that allowed the projection of a large, clear, longer string of pictures.

This device, renamed the “théâtre optique,” or optical theater, showed a series of images that were initially painted on glass plates connected by a flexible band that unwound from one reel and rewound onto another. These slides could briefly lie flat in front of the light source for sharp projection onto a mirror before being reflected onto the final screen. Reynaud next painted on a flexible roll of gelatine bordered by cardboard or cloth. This strip wound its way through a series of rollers before passing by the mirrored surface for projection. One of the inspirations for the overall design was apparently the mechanics of the nineteenth-century bicycle with its large front wheel, long chain, and smaller rear wheel, driven by pedals and a crank (Myrent 1989: 193). The initial patent application carefully outlined the components for the apparatus, including gears, rollers, and take-up reels, but he also left vague the definitions of the “flexible band,” and allowed that the machine would work whether the “successive poses” were opaque or transparent, and he even acknowledged that the designs could be printed mechanically onto the malleable strip. A catalogue for a 1982 exhibition on “100 Years of French Animation” credits Reynaud with launching a new medium: “With characters drawn and colored on a large perforated strip of film, animation existed before the cinema!” (Maillot 1982: n.p.).

Importantly, Reynaud's optical theater allowed “unlimited durations allowing for real animated scenes” (Lonjon 2007: 201). The patent explained that this device decisively surpassed such repetitive, circular devices as the zoetrope and praxinoscope (Reynaud and Sadoul 1945: 55). A linear “show” was now possible rather than the spinning discs and strips with their brief loops that had preceded the optical theater. As Nicolas Dulac and André Gaudreault point out, “Reynaud's apparatus thus went beyond mere gyration, beyond the mere thrill of seeing the strip repeat itself … narrative had taken over as the primary structuring principle.” Reynaud offered “a new paradigm within which narration would play a decisive role” (Dulac and Gaudreault 2006: 239). Individual titles lasted from 8 to 15 minutes and consisted of 300 to 700 images, so the duration of Reynaud's subjects far exceeds the subsequent 50-second Lumière films, anticipating instead the length of eventual one- and two-reel short films. Pauses were built into the presentations, and they still seem to have had a rather slow projection time, averaging one second per image. However, Reynaud also designed the drawings to allow for some repetitions. For instance, when Harlequin first sneaks over the wall in Pauvre Pierrot (Poor Pierrot, 1892), he acts rather hesitant. Reynaud would stop advancing the band of animation, reverse it to show the character climb back up the wall, then crank it forward again as Harlequin finally decided to drop into the garden for good (Auzel 1998: 68). When a character danced with delight, Reynaud could also draw the frames in such a way that they could be shown forward, then backward, then forward again, but it looked like three sequential dance steps. Significantly, such back and forth maneuvers were possible because Reynaud was actually projecting two images. A magic lantern projected the static painted slide of the background set which was constant, while only characters and occasional objects were drawn on the moving strip. Thus, a composite image resulted that prefig...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Introduction: The Rise of Animation in France

- Chapter 2: Silent Animation: Emile Cohl and his Artisanal Legacy

- Chapter 3: French Animation and the Coming of Sound

- Chapter 4: Toward an Alternative Studio Structure

- Chapter 5: French Animation's Renaissance

- Chapter 6: Conclusion: French Animation Today

- References

- Further Reading

- Plates

- Index