- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Critical Care Management of the Obese Patient

About this book

This book provides health professionals with sound clinical advice on managementof the obese patient admitted into hospital. It addresses all aspects of the patient's care, as well as serving as a resource to facilitate the management of services, use of clinical information, and negotiation of ethical issues that occur in intensive care. As the number of obese patients in intensive care continues to grow, this book will serve as a comprehensive clinical resource for everyday use by both obesity specialists and emergency medicine physicians.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Critical Care Management of the Obese Patient by Ali El Solh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Emergency Medicine & Critical Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Physiology and Consequences of Obesity

1

Cardiovascular Physiology in Obesity

KEY POINTS

- Obesity, particularly class III obesity, produces central hemodynamic changes that cause alterations in cardiac morphology and ventricular function which may lead to heart failure.

- In the absence of systemic hypertension, hemodynamic changes include increased total and circulating blood volume, high cardiac output, low systemic vascular resistance, left ventricular dilatation, eccentric left ventricular hypertrophy and elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure.

- Left ventricular function in long-standing obesity is often characterized by impaired diastolic filling and infrequently associated with systolic dysfunction.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a growing epidemic in the United States and worldwide [1–4]. In the United States, 33 of the 50 states have a prevalence of obesity ≥ 25% [2]. Ten years ago the prevalence of obesity was < 25% in all 50 states [2,3]. Worldwide the prevalence of obesity ranges from 12 to 80%, with the highest rates occurring in the more industrialized nations [1]. Obesity is traditionally categorized in terms of body mass index (BMI). Current definitions of overweight and obesity in adults are as follows: overweight: BMI of 25.0–29.9 kg/m2; class I obesity: BMI of 30.0–34.9 kg/m2; class II obesity: BMI of 35.0–39.9 kg/m2; and class III obesity: BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2. Class III obesity is sometimes referred to as severe, extreme or morbid obesity [1–4]. The term “super obesity” is used to describe patients whose BMI is ≥ 50 kg/m2 [4].

A relationship between obesity and the heart has been recognized since ancient times, as noted by Senac (aphorism no. 11) and Hippocrates in his oft quoted aphorism no. 44: “Sudden death is more common in those that are naturally fat than in the lean” [5]. In 1806 Corvisart described adipose surrounding the heart in obese subjects and suggested that in obese people the heart was “oppressed by enveloping fat” [5]. In 1847 William Harvey reported a post-mortem examination of a corpulent man and wrote that “the heart was large, thick and fibrous, with a considerable quantity of adhering fat, both in its circumference and over its septum” [5]. Harvey reported that shortly before his death this patient developed facial lividity, difficult breathing and orthopnea, perhaps the first description of obesity cardiomyopathy. During this period of time it was presumed that excessive epicardial fat was responsible for cardiac dysfunction in patients with severe obesity. The term “adipositas cordis” was used to describe this phenomenon. In 1933 Smith and Willius published autopsy findings of 136 obese subjects whose excess weight ranged from 14 to 175% [6]. In nearly all of the obese subjects heart weight exceeded that predicted for normal body weight [6]. Subsequent studies established that myocardial fat content in obese persons is no different than that of lean individuals [5,7,8]. In addition, several case reports and small series characterized what would subsequently become known as the sleep apnea/obesity hypoventilation syndrome or “Pickwickian” syndrome [9–11]. Renewed interest in the cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology of obesity occurred with publication of hemodynamic studies of extremely obese adults by Alexander and colleagues in 1959 [12]. The purpose of this chapter is to review cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology in obesity, based primarily on research performed and published during the last half-century. This chapter will focus on central and peripheral hemodynamics, emphasizing their effects on cardiac morphology and ventricular function and the development of heart failure. The pathophysiological effects of systemic hypertension and the sleep apnea/obesity hypoventilation syndrome on the heart will also be discussed, as will the effects of weight reduction. The relationship between obesity and coronary artery disease is complex and is beyond the scope of this review. Neither this issue nor the matter of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in obesity will be addressed in this chapter.

CARDIOVASCULAR HEMODYNAMIC ALTERATIONS ASSOCIATED WITH OBESITY

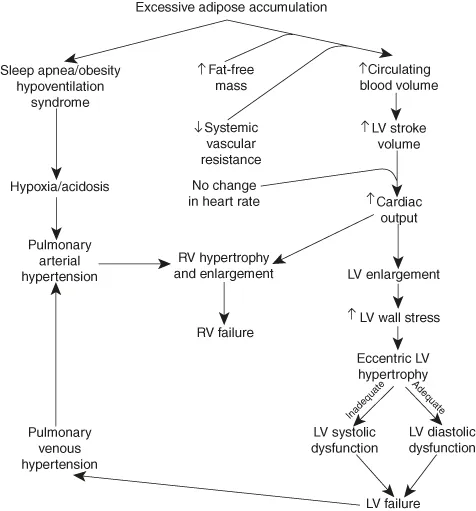

Obesity, particularly morbid obesity, produces a variety of hemodynamic changes that may predispose to alterations in cardiac morphology and ventricular function [12–22]. Figure 1.1 summarizes the major cardiovascular hemodynamic alterations associated with obesity and their pathophysiological sequelae. This figure may be used for reference in this section and in subsequent sections on cardiac morphology and ventricular function.

Central cardiovascular hemodynamics

Obesity produces an increase in total and circulating blood volume [4,12–14]. This phenomenon was originally attributed entirely to excessive adipose accumulation, but recent evidence indicates that increased fat-free mass plays an important role [4,15,16]. In normotensive obese individuals, systemic vascular resistance is lower than in normotensive lean persons [4,12–14,17,18]. The increase in circulating blood volume together with reduced systemic vascular resistance results in an increase in cardiac output. Indeed, Alexander et al. demonstrated that cardiac output increased in proportion to the excess in body weight in obese subjects [12–14]. Heart rate did not differ from that predicted with ideal body weight in this study and stroke volume increased in proportion to the excess in body weight [12–14]. Thus, the increase in cardiac output associated with obesity is entirely attributable to an increase in left ventricular (LV) stroke volume [12–14]. Oxygen consumption and arteriovenous oxygen difference are reportedly increased in moderately to severely obese patients despite the high cardiac output state [4,12–14]. In a study of 10 moderately to severely obese subjects, DeDivitiis and colleagues confirmed these findings and noted the presence of increased LV work and stroke work [17]. DeDivitiis and coworkers also reported a decrease in LV Dp/dt in this study, possibly suggesting the presence of an intrinsic defect of myocardial contractility [17]. They reported right ventricular (RV) end-diastolic pressure and mean pulmonary artery pressure values in excess of those predicted for ideal body weight [17]. In actuality, right heart pressures associated with obesity reported in the literature are somewhat variable, depending in part on the contribution of left heart failure, sleep apnea/obesity hypoventilation and other pulmonary disorders [12–19]. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and LV end-diastolic pressure values reported in the literature are similarly variable, ranging from high-normal to markedly elevated [12–14,17–19]. However, studies assessing central hemodynamics during exercise have uniformly noted a marked increase in LV filling pressure even with modest exertion, often reaching levels sufficient to produce pulmonary edema [4,13,18]. Whether extreme physiological stresses such as those encountered in the critical care setting produce similar results is unproven, but likely. Thus, it appears that moderate to severe obesity raises cardiac output at the expense of LV filling pressure. The aforementioned pathophysiological observations are applicable primarily to normotensive obese patients. Systemic hypertension tends to intensify these hemodynamic responses and will be discussed in a later section.

Distribution of obesity may be an important issue as individuals with central obesity have been shown to have higher systemic vascular resistance and lower cardiac output than those with a centripetal fat distribution [4,19]. It is also important to emphasize that central hemodynamic studies have been performed predominantly on class II and III obese subjects. The applicability of data derived from these studies to overweight and class I obese patients is uncertain.

Peripheral hemodynamics

Adipose tissue is surrounded by an extensive capillary network [4]. Adipocytes are located close to vessels with high permeability and low hydrostatic pressure. This, coupled with a short distance for transport, facilitates movement of molecules to and from adipocytes [4]. The resting blood flow in adipose tissue is 2–3 ml/min/100 g of fat and can increase up to 10-fold [4]. Adipose tissue makes up a substantial proportion of total body weight. The interstitial portion of adipose tissue contains a large quantity of fluid [4]. This fluid, however, is not readily accessible to the central circulation because blood flow per unit of adipose tissue is reduced by the vasodilatory effect of B1 receptors [4]. Although cardiac output increases with total fat mass the perfusion per unit of adipose tissue actually decreases with increasing percentage body fat [4]. Because the enlarged bed of adipose tissue in the obese is less vascularized than other tissue, the observed increase in stroke volume and cardiac output cannot be explained by fat mass alone [4]. As previously noted, recent studies have confirmed that fat-free mass plays an important and possibly predominant role in the previously-noted central hemodynamic alterations [4,15,16].

Figure 1.1 Major cardiovascular hemodynamic alterations associated with uncomplicated obesity and their pathophysiological sequelae.

An important concept in peripheral hemodynamics in obesity is the role of the adipocyte as an endocrine and paracrine organ. Adipokines released by adipocytes play an important role in modulating peripheral hemodynamics. Leptin helps modulate energy expenditure and sympathetic tone through the hypothalamus. In the obese, a pattern of selective leptin resistance has been identified [20]. It is characterized by continued leptin resistance to satiety, but not to its effect on sympathetic tone [20]. Leptin resistance is thought to be mediated by down regulation of the leptin receptor by leptin itself, producing increased circulating leptin levels, increased sympathetic tone, and peripheral vasoconstriction [20]. Three decades ago Messerli et al. demonstrated that plasma renin activity was higher in normotensive obese subjects than in normotensive lean subjects, suggesting activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in obesity [21]. More recently, Massiera and colleagues reported increased expression of adipose angiotensinogen in rats with increased fat mass sufficient to be detected in the circulation [22]. This study provides additional evidence of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation in obesity. These endocrine and paracrine activities of adipose may produce vasoconstriction and an increase in systemic vascular resistance. In doing so they may predispose to obesity-related hypertension.

Little information exists concerning regional distribution of blood flow in other organ beds in obesity. Older studies in extremely obese adults suggest that cerebral blood flow is mildly reduced, splanchnic blood flow is mildly increased and renal blood flow is low-normal to normal [13].

EFFECT OF OBESITY ON CARDIAC MORPHOLOGY

Left ventricle

Post-mortem studies of extremely obese subjects have uniformly shown increased LV wall thickness and microscopic LV hypertrophy [23–25]. However, these studies did not exclude patients with hypertension and other comorbidities. Early echocardiographic studies in morbidly obese subjects reported LV enlargement in 8–40%, increased LV wall thickness in 6–56%, and increased LV mass in 64–87% [23]. The wide ranges reported may be attributable to differences in comorbidities and in the severity and duration of obesity [23]. Numerous studies have compared various measures of LV morphology in obese and lean subjects [23–28]. The severity of obesity ranged from mild to severe. In most of these studies the measure of LV morphology (diastolic chamber size, ventricular septal thickness, posterior wall thickness, mass, mass index, mass/height index) was significantly higher/greater in obese than in lean subjects. A study by Kasper and colleagues of 409 lean patients and 43 patients whose BMI was > 35 kg/m2 with heart failure showed a higher prevalence of dilated cardiomyopathy in obese than in lean patients [29]. A specific cause was noted in 64% of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contributors

- Preface

- Part I: Physiology and Consequences of Obesity

- Part II: Positive Pressure Ventilation

- Part III: Management of Obesity Complications in Critical Care

- Part IV: Hemodynamic Monitoring and Radiological Investigations

- Part V: Postsurgical Management

- Part VI: Pharmacology

- Part VII: Prognosis and Ethics

- Multiple Choice Questions

- Answers to Multiple Choice Questions

- Index