![]()

PART 1

Dynamics of Solids

![]()

Chapter 1

Motion within Solids

The concept of stress and strain waves emerges from the equations of motion in elastic continuum. Uniaxial propagation is particularly well-studied because of its practical importance. The waves can be altered within their propagation by dispersion and dissipation. For viscoelastic solids, we can address the effects of behavior sensitive to strain in a linear framework.

1.1. Representation of the medium

1.1.1. Framework of continuum mechanics

The problem for the engineer is to describe the position (or displacement) of solids and fluids. This mechanism is of a macroscopic scale. On this macroscopic scale, solid or fluid matter can be seen as continuous, which is not the case at the microscopic level of particles, molecules and atoms. The macroscopic scale is not the same for all materials: a fraction of a millimeter for a metal, a few inches for geomaterials such as rock or concrete.

In this book, we only refer to classical mechanical engineering knowledge of continuum mechanics and structural strength. This chapter intends to recall the basics of continuum motion when these can be described by linear equations, such as in the context of small strains and elastic or viscoelastic material behavior.

1.1.2. Representation of motion

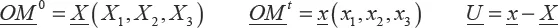

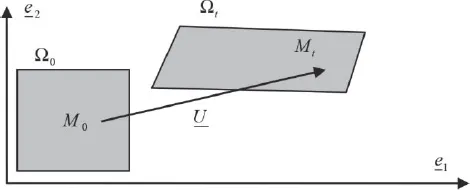

The motions in matter are identified in an affine Euclidean space. A point in matter which occupies position

M0 at time 0, defined by the vector

is in position

Mt at time

t, defined by the vector

. A certain amount of matter that occupies the simply connected domain Ω

0 at time 0, also occupies the simply connected domain Ω

t at time

t (

Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Material field in its initial position and after transformation

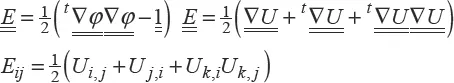

The description of these movements can be given from two points of view: one is called “Lagrangian” and the other is called “Eulerian”. The Lagrangian description involves following the matter points in their motion. The current position, or displacement, is expressed depending on the initial position and t, using a continuous vector function [1.2] that defines the trajectories (this is a bijection of Ω0 to Ωt, due to the continuity of displacement of the system):

The Eulerian description involves the knowledge of the velocity field at each moment relative to the current position. The Eulerian description of the velocity field involves specifying the velocity of the particle passing position

at time

t [1.3]:

If the Eulerian velocity field does not depend on time, the motion is stationary. Eulerian representation is mainly used for fluids and materials undergoing very large strains. In the remaining chapter, we use the Lagrangian point of view. The strain is characterized by the Green–Lagrange strain tensor [1.4]:

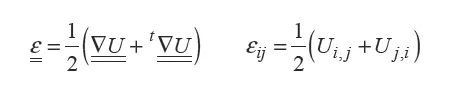

In many cases for solids, displacements and strains are very small (0.001% elongation, for example). A linearization is then performed by retaining only the first-order infinitesimal. This is called the linearized strain tensor [1.5]:

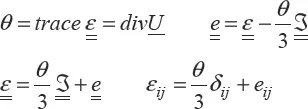

It is this tensor that will be most widely used. Each component has a simple physical significance: εii represents the relative elongation in direction i. εij (i ≠ j) represents the angular distortion relative to the two directions i and j. The tensor trace, equal to the divergence of the displacement vector, represents the relative change in volume. The partition of the strain tensor in its spherical part, which is related to the change in volume, and its deviatoric part, which is related to the change of form [1.6], is used:

1.1.3. Representation of internal forces

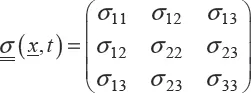

In a continuum, internal forces can be represented either by a scalar field, pressure

, or by a tensorial field, the Cauchy stress tensor. In an orthonormal frame, this tensor is represented by a symmetric matrix [1.7].

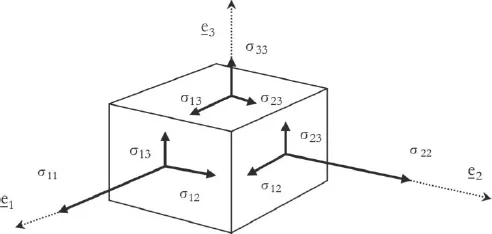

Figure 1.2 shows a representation of the components of the stress tensor of a material whose faces are normal to the reference axes wherein the said tensor is expressed:

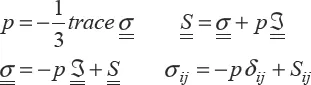

For solids, it is customary to partition the stress tensor into a so-called “spherical” or isotropic part, characterized by pressure p, and a so-called “deviatoric” part [1.8]:

The representation of internal forces by pressure concerns, a priori, non-viscous fluids. However, when shocks occur in solids, the pressure can become very large and the terms of the deviatoric part (shear stress) may be negligible compared to the pressure. In these cases, it is possible to retain only pressure to represent internal forces. This is a hydrodynamic model of a material.

Figure 1.2. Representation of the components of the Cauchy stress tensor on a piece of material

Writing the behavior or resistance of a material logically involves stress tensor invariants. Besides the main constraints (σI, σII, σIII) that are the eigenvalues of the matrix representing the stress tensor, various invariants of this tensor are used:

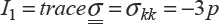

– The first invariant of the stress tensor, which defines the pressure [1.9]:

– The second invariant of the deviator tensor, which ...