- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Companion to Chinese Archaeology

About this book

A Companion to Chinese Archaeology is an unprecedented, new resource on the current state of archaeological research in one of the world's oldest civilizations. It presents a collection of readings from leading archaeologists in China and elsewhere that provide diverse interpretations about social and economic organization during the Neolithic period and early Bronze Age.

- An unprecedented collection of original contributions from international scholars and collaborative archaeological teams conducting research on the Chinese mainland and Taiwan

- Makes available for the first time in English the work of leading archaeologists in China

- Provides a comprehensive view of research in key geographic regions of China

- Offers diverse methodological and theoretical approaches to understanding China's past, beginning with the era of established agricultural villages from c. 7000 B.C. through to the end of the Shang dynastic period in c. 1045 B.C.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Companion to Chinese Archaeology by Anne P. Underhill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Current Issues in Chinese Archaeology

CHAPTER 1

Introduction: Investigating the Development and Nature of Complex Societies in Ancient China

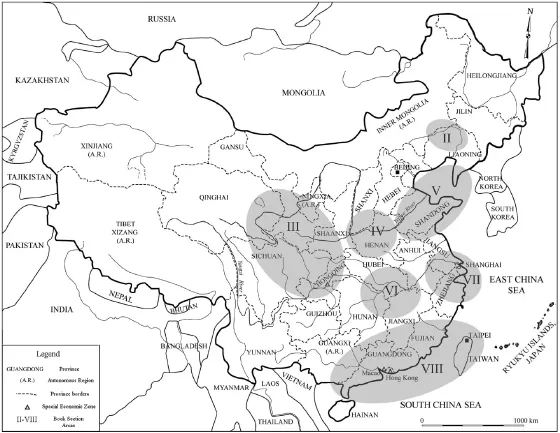

There are two main goals of this book. One goal is to reveal the diverse methodological and theoretical approaches to understanding prehistoric and early historic era societies that characterize current research efforts in Chinese archaeology. The authors discuss geographical areas that later became part of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC) (Figure 1.1). They are major scholars in the field of Chinese archaeology from diverse areas of the globe, including members of collaborative Sino-foreign research teams. The important contributions of some of the authors from mainland China are published in English for the first time. Chinese archaeology is a thriving field with scholars continuing to develop diverse methods of fieldwork and interpretation. The chapters demonstrate a variety of thoughtful approaches to investigating the past. No single theoretical or methodological approach characterizes current research about ancient China.

Figure 1.1 Modern political areas and geographic areas (shaded) referred to in consecutive sections of this book.

(Figure by Pauline Sebillaud and Andrew Womack.)

The second major goal is to provide English readers with new data about ancient China that are significant for understanding regional variation in social, economic, and political organization over time. The chapters offer diverse interpretations about the organization of individual settlements and regions, involving a range from small-scale, sedentary societies, to polities including several settlements. I believe that the archaeological record of East Asia is extremely important for global comparative research on the development and nature of ancient complex societies. The chapters in this book show that it is essential to consider the archaeological record for many regions of China, not just the Central Plain area of the Yellow river valley where the earliest undisputed states and writing systems developed. Furthermore, the chapters reveal significant regional diversity in the trajectories of change and in the nature of the societies that developed. After explaining my decisions about the subject matter and organization of the book, I offer some suggestions for future avenues of research on different kinds of social relations in the past.

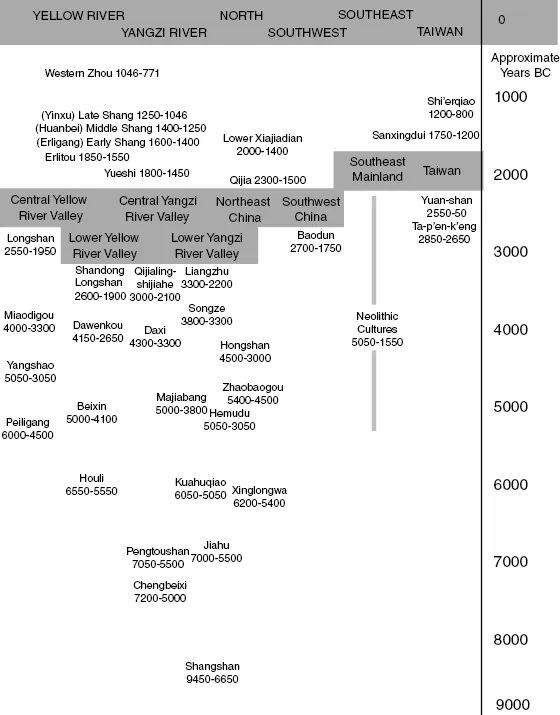

The chapters in this book are organized by sections centered on major geographic areas rather than by groupings using the terms “Neolithic period” and “early Bronze Age” as in most other publications about Chinese archaeology. These terms are overly simplistic as chronological indicators, since in some areas such as the Southeast, relatively small-scale societies flourished for millennia after the emergence of early states and the onset of bronze production (tools, ornaments, and/or vessels) further north (Figure 1.2). These terms also mask significant regional variation with respect to social, economic, and political organization over time, often leading to assumptions about homogeneity in social, political, and economic organization.

Figure 1.2 Time line of cultures discussed in this book.

(Figure by Andrew Womack.)

My priority is to illustrate a range of research on prehistoric and early historic era societies (c.7000–1000 bc), rather than attempting to cover briefly several eras over a very long time span. It is not possible, therefore, to include chapters about important issues such as the origins of agriculture during the early Holocene, or chapters emphasizing eras after the late Shang period – the first period with an undisputed, fully developed writing system. For each geographic area covered, the chapters provide interpretations about social relations at various spatial scales on the basis of archaeological remains for more than one era. They make it clear that complex societies of varying forms developed in several regions and during several periods. There are discussions about relatively early, small-scale societies and about large-scale societies, variously defined, for each major geographic area.

It is a challenge to group the contents of the chapters into meaningful geographic areas. The main point to emphasize is that they are macro-regions. Each one contains smaller physiographic regions that deserve intensive study in their own right (Figure 1.1). In each section, some chapters refer to large geographic areas, while others discuss smaller areas. The organization of the book enables readers to trace trajectories of social change from chapter to chapter and to observe diverse approaches to archaeological research within each macro-region. The following major geographic areas are included: the Northeast, the Upper Yellow River and Upper Yangzi River regions, Western Central Plain region and environs, Eastern Central Plain region and environs, the Middle Yangzi River region, the Lower Yangzi River region, and the Southeast. A single book can only take initial steps in portraying the regional variation in social, economic, and political organization that developed in the areas currently comprising mainland China and Taiwan. I hope to see future books discussing in more detail the large, diverse regions that are included in this volume. Other volumes also are needed for different regions in the Southwest and Northwest that could not be covered here, including modern Yunnan, Tibet, and Xinjiang. My decision was to focus on regions that had been more extensively introduced in the English literature, so readers could recognize the significance of the current research efforts. It was not possible to include chapters on all of the fine research being done in the selected regions, either.

Key themes in the chapters include investigation of internal settlement organization, household subsistence production, regional settlement patterns, the nature of early urbanism, craft specialization, political economy, and the ideological basis of social hierarchy. Given the relatively abundant English-language publications about burials from different regions of mainland China in particular, I asked the authors to focus on residential remains whenever feasible. While the chapters reveal significant diversity in the development and nature of early complex societies, they also illustrate general patterns that characterize more than one geographic region such as increase in interaction among communities, development of settlement hierarchies, increase in nucleation of population at single settlements, and increase in degree of social inequality over time. The investigators share many research goals with archaeologists who work in other areas of the world. In addition, as everywhere with professional archaeologists, there are debates about interpretation of remains. At the same time the rich descriptive data provided by authors make it possible for readers to consider their own interpretations.

The chapters focusing on relatively small-scale societies raise issues that are relevant to analysis of many other archaeological sites and regions. For example, what constitutes the community? How can we interpret spatial groups of houses within a settlement? How can we relate these spatial groups to different kinds of social groups that may have existed? Or, what might these spatial groups indicate about the nature of economic organization? At a larger scale, how can we interpret clusters of settlements within a relatively small region? Some scholars make an effort to address these issues by considering the nature of social groups formed on the basis of kinship. Other chapters that discuss larger-scale societies also argue that analysis of kinship relations continued to be very important for the organization of early complex societies. Similarly, some authors emphasize social inequality with respect to social groups, in addition to that for individuals. The tendency in the North American archaeological literature is to focus on the rise of particular kinds of individual leaders and their strategies to increase personal power. Archaeological research in China shows that it is also important to consider agency from the perspective of social groups. In addition, the chapters discuss an often neglected dimension of research on the development of complex societies: change in the degree and nature of social integration at the site and regional levels. For example, some chapters refer to increased cooperation among members of kin groups with respect to economic and ritual affairs. Despite the challenges, the goal of understanding intra-group relations at varying social and spatial scales is essential. It often is assumed that social hierarchy was a key organizing principle, but we also should consider how cooperative relations played a role in social, economic, and political life.

A key issue for authors who write about relatively large-scale societies is the development and nature of urbanism. The chapters reveal fascinating variation in the nature of settlements identified as cities with respect to scale, layout, and organization. In some regions, there is a relatively dispersed pattern of urbanism, while others have sites in a more nucleated pattern. Some of the recently investigated urban areas are enormous in scale. The chapters show that data from several regions of China need to be considered as archaeologists seek to compare and understand the nature and functions of areas that comprise urban centers. For these discussions it is not sufficient to include only sites from areas of the Central Plain in modern Henan province where the Erlitou and Shang states developed. Differences in the degree and nature of settlement nucleation and settlement layout (involving, for example, varying numbers of rammed-earth walls and ditches, with habitation remains in areas beyond the walls as well as within them), need to be explained. These differences are indicative of variation in the processes involved in the establishment and operation of the urban settlements. Some urban centers were built upon earlier settlements, while others were newly established. Research also is providing important new data about subsistence and craft production in urban centers in comparison to the smaller communities around them. It is clear that economic data at the regional level are important for understanding early urbanism in China.

The chapters provide much food for thought about the challenging task of explaining how and why different kinds of social changes took place in various regions of what later became the PRC and ROC. They illustrate a thoughtful process by which scholars continue to evaluate approaches to interpreting the past. Many authors aim to identify major differences in social, economic, and/or political organization from one phase to another. Some authors emphasize an ecological approach to spurring social and economic change, while others emphasize the importance of technological change, or the importance of control over the production, distribution and or use of highly valued goods. Some scholars draw analogies about social organization on the basis of observations regarding cultural traditions during various historical eras. A major concern for every author is the protection of cultural heritage in China, which is the topic of the second chapter in the introductory section of this book.

The chapters in this Companion illustrate the importance of explaining the nature of each form of regional organization that developed during the later prehistoric and early historic eras, rather than focusing on the application of labels such as “state” or “chiefdom.” It is clear that diverse complex societies developed in a number of regions of China. There are several challenges ahead for archaeologists who research this issue, too. One will be to refine the chronology of large, individual sites in order to understand phases of expansion and contraction of settlement areas over time. This will make it possible to refine arguments about social and economic organization at the site and regional levels. Another challenge will be more study of individual regions by means of systematic, regional surveys for information about changes in settlement patterns over time. Research at the regional level also will benefit from more excavation at sites involving similar methods of data collection, including screening and flotation. This will facilitate an understanding of the nature of social relations among communities over time.

I hope that the impressive work of the scholars in this volume inspires more research on social change in different regions of China. The following suggestions are aimed to facilitate this research and to provide greater understanding of the growing data from China about the development and nature of early complex societies. Every year there are striking technological innovations that aid archaeological research, but in my view some basic methodological issues with respect to the research process are equally important for all of us to keep in mind.

We should aim to include explicit statements about the goals of research and how particular kinds of data were collected in order to address specific research questions. There should be more explicit explanations about the metho...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Notes on Translators and Other Assistants

- PART I: Current Issues in Chinese Archaeology

- PART II: The Northeast

- PART III: The Upper Yellow River and Upper Yangzi River Regions

- PART IV: The Western Central Plain Region and Environs

- PART V: The Eastern Central Plain Region and Environs

- PART VI: The Middle Yangzi River Region

- PART VII: The Lower Yangzi River Region

- PART VIII: The Southeast

- Index