Process Intensification Technologies for Green Chemistry

Engineering Solutions for Sustainable Chemical Processing

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Process Intensification Technologies for Green Chemistry

Engineering Solutions for Sustainable Chemical Processing

About this book

The successful implementation of greener chemical processes relies not only on the development of more efficient catalysts for synthetic chemistry but also, and as importantly, on the development of reactor and separation technologies which can deliver enhanced processing performance in a safe, cost-effective and energy efficient manner. Process intensification has emerged as a promising field which can effectively tackle the challenges of significant process enhancement, whilst also offering the potential to diminish the environmental impact presented by the chemical industry.

Following an introduction to process intensification and the principles of green chemistry, this book presents a number of intensified technologies which have been researched and developed, including case studies to illustrate their application to green chemical processes.

Topics covered include:

• Intensified reactor technologies: spinning disc reactors, microreactors, monolith reactors, oscillatory flow reactors, cavitational reactors

• Combined reactor/separator systems: membrane reactors, reactive distillation, reactive extraction, reactive absorption

• Membrane separations for green chemistry

• Industry relevance of process intensification, including economics and environmental impact, opportunities for energy saving, and practical considerations for industrial implementation.

Process Intensification for Green Chemistry is a valuable resource for practising engineers and chemists alike who are interested in applying intensified reactor and/or separator systems in a range of industries to achieve green chemistry principles.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1.1 Introduction

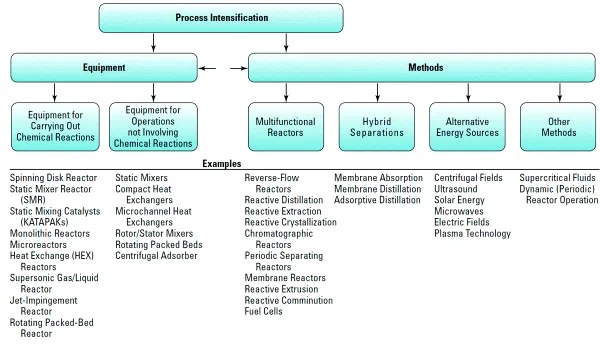

1.2 Process Intensification: Definition and Concept

1.3 Fundamentals of Chemical Engineering Operations

1.3.1 Reaction Engineering

1.3.1.1 Plug Flow Reactor

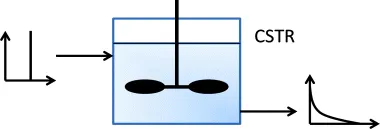

1.3.1.2 Continuously Stirred Tank Reactor

1.3.1.3 The Plug-Flow Advantage

- Much of the material in the reactor will spend too long in the reactor (due to the long tail in the RTD) and will consequently be ‘overcooked’. The main problem with this is that it allows competing reactions to become more significant.

- Much of the material will be in the reactor for less than the desired residence time. It will therefore not reach the desired level of conversion.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Process Intensification: An Overview of Principles and Practice

- Chapter 2: Green Chemistry Principles

- Chapter 3: Spinning Disc Reactor for Green Processing and Synthesis

- Chapter 4: Micro Process Technology and Novel Process Windows – Three Intensification Fields

- Chapter 5: Green Chemistry in Oscillatory Baffled Reactors

- Chapter 6: Monolith Reactors for Intensified Processing in Green Chemistry

- Chapter 7: Process Intensification and Green Processing Using Cavitational Reactors

- Chapter 8: Membrane Bioreactors for Green Processing in a Sustainable Production System

- Chapter 9: Reactive Distillation Technology

- Chapter 10: Reactive Extraction Technology

- Chapter 11: Reactive Absorption Technology

- Chapter 12: Membrane Separations for Green Chemistry

- Chapter 13: Process Intensification in a Business Context: General Considerations

- Chapter 14: Process Economics and Environmental Impacts of Process Intensification in the Petrochemicals, Fine Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals Industries

- Chapter 15: Opportunities for Energy Saving from Intensified Process Technologies in the Chemical and Processing Industries

- Chapter 16: Implementation of Process Intensification in Industry

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app