- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An innovative new approach to addiction treatment that pairs cognitive behavioural therapy with cognitive neuroscience, to directly target the core mechanisms of addiction.

- Offers a focus on addiction that is lacking in existing cognitive therapy accounts

- Utilizes various approaches, including mindfulness, 12-step facilitation, cognitive bias modification, motivational enhancement and goal-setting and, to combat common road blocks on the road to addiction recovery

- Uses neuroscientific findings to explain how willpower becomes compromised-and how it can be effectively utilized in the clinical arena

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cognitive Therapy for Addiction by Frank Ryan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Clinical Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Tenacity of Addiction

Introduction and Overview

Why does addiction exert such a tenacious grip on those who fall under its spell? In this book I propose that the answer to this question lies largely within the cognitive domain: the persistence of addiction is viewed as a failure or aberration of cognitive control motivated by the enduring and unconditional value assigned to substances or behaviours that activate neural reward systems. I shall outline how addictive behaviour endures because it recruits core cognitive processes such as attention, memory and decision making in pursuit of the goal of gratification, the associated alleviation of negative emotions, or both. This recruitment process is often covert, if not subversive, and operates implicitly or automatically in the context of impaired inhibitory control. The habituated drug user is effectively disarmed when exposed to a wide range of cues that generate powerful involuntary responses. The best, and often the only, option is to mount a rear-guard action from the command and control centre of the brain. This sets the scene for a reappraisal of cognitive therapy applied to addiction. Beginning with an overview of the plan and scope of the book, this introductory chapter outlines a cognitive perspective on addiction. It goes on to address shortcomings in historical and current therapeutic approaches to addictive behaviour and includes a brief review of the equivocal and occasionally puzzling findings generated in clinical trials. It concludes with an overview of CHANGE, the re-formulated account of psychological intervention based on cognitive, motivational and behavioural principles in a cognitive neuroscience framework that forms the basis of this text.

Terminology

I have avoided the use of the term addict unless quoting from other sources. I do not think the manifestation of a particular behaviour should be used to denote an individual, in the same way that I would avoid use of terms such as a depressive or an obsessive in other circumstances. Of course, many of those who develop addictive disorders choose to refer to themselves as ‘addicts’. That is entirely appropriate for them, but I believe choosing to designate oneself as an addict is different from being so labelled by another. However, beginning with the title, I readily adopt the term addiction. Here, I apply a functional definition emphasizing the apparent involitional nature of addictive behaviour, its persistence in the face of repeated harm to self and others, and a tendency for drug seeking and taking to recur following cessation. In truth, addictive behaviour and its concomitant cognitive, behavioural and neurobiological facets occur on a continuum of varying, but often escalating, frequency and quantity or dosage. This is why attributing a static label such as addict is likely to miss the point, even if occasionally seeming to hit the nail on the head. There will be some interchange between the terms addiction, substance use and substance misuse according to the context. Generally, however, my use of the term addiction implies that the individual or group referred to meet standard diagnostic criteria for addictive disorders or dependence syndromes. Similarly, and again given pride of place on the front cover, I have opted for the term cognitive therapy rather than cognitive behavioural therapy. This decision is pragmatic rather than doctrinal but does authenticate the emphasis on cognition throughout the book. Both terms feature in the text, and anything deemed purely cognitive can easily be assimilated into the broader church of CBT.

Scope

Addiction has long been a source of fascination for theorists from a wide variety of scientific backgrounds. West (2001) listed a total of 98 theoretical models of addiction, which he classified broadly as either biological, psychological or social in orientation and content. Here, I do not attempt to review this diverse body of work. Nonetheless, West's taxonomy, referencing a ‘biopsychosocial’ framework, serves as a reminder that addiction is a complex, multifactorial, phenomenon. The main focus here is on understanding the neurocognitive and behavioural mechanisms of addiction and translating this knowledge into more effective therapeutic intervention. Most of the theoretical and empirical findings cited are based on either clinical trials or experimental paradigms involving drug administration, drug ingestion and drug withdrawal in humans and other species. For the most part, the substances at the root of the problems addressed in this text will therefore include opiates, cocaine, amphetamines, alcohol, nicotine and cannabis. At the time of writing, preparations for the fifth revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) are well underway. The term dependence, also central to the ICD-10 (WHO, 1992), is apparently being dropped. This is apparently due mainly to the possibility of conceptual confusion stemming from its dual meaning referring to either uncontrolled drug use, or normal neuroadaptation when, for example, narcotic analgesics are prescribed to alleviate chronic pain (O'Brien, 2011). The forthcoming taxonomy, due to be published in 2013, will therefore refer to ‘Addiction and Related Disorders’. Subcategories will refer to ‘alcohol use disorder’, ‘heroin use disorder’ and so on.

Gambling and other compulsive appetitive behaviours

In the forthcoming diagnostic manual on addictive disorders, the chapter on addiction will also include compulsive gambling, currently classified as an impulse control disorder along with trichotillomania and kleptomania in DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Consistent with this, Castellani and Rugle (1995) demonstrated that problem gambling is associated with tolerance, withdrawal, urges and cravings, high rates of relapse and high levels of co-morbidity for mental health problems. More fundamentally, from a cognitive neuroscience point of view, it is what goes on in the brain that matters, whether this is triggered by heroin, cocaine, alcohol or indeed gambling. By way of illustration, an intriguing series of case studies provides a more clinical dimension to the motivational power of dopamine, a key neurotransmitter in reward processing, in relation to gambling. Dodd et al. (2005) reported how they encountered 11 patients over a two-year period at a movement disorders clinic with idiopathic Parkinson's disease who developed pathological gambling. All of these patients were given dopamine agonist therapy such as pramipexole dihydrochloride. Seven of these patients developed pathological or compulsive gambling within 1–3 months of achieving the maintenance dose or with dose escalation. One 68-year-old man, with no history of gambling, acquired $200,000 of gambling debt. On cessation of dopamine agonist therapy his urge to gamble subsided and eventually ceased, an outcome also observed in the seven other patients that were available for follow-up. More generally, other behaviours with a propensity to become compulsive include online activities such as Internet addiction and gaming. My view is that a behaviour such as gambling that activates reward neurocircuitry with wins, and probably downregulates the same system with losses, is liable to become compulsive in susceptible individuals. Consequently, aspects of compulsive gambling and other behaviours where motivation to desist is compromised fall within the scope of this book.

The plan of the book

The book begins with a brief critical appraisal of existing approaches, in particular cognitive and behavioural approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and cognitive therapy itself (Chapter 2). This review is highly selective insofar as it focuses on shortcomings and unanswered questions, such as the finding that markedly diverse therapeutic approaches, including CBT, deliver broadly equivalent clinical outcomes. In successive chapters (3 and 4), I address first the core learning processes that contribute to the development of addiction and their neurocognitive bases, as well as delineating the predispositional role of exposure to adversity. Next, a conceptual framework that accommodates implicit cognitive and behavioural processes along with more familiar targets such as consciously available beliefs is outlined. The conclusion is that the most plausible way to regulate the former is by augmenting the latter: strategies that enhance executive control, metacognition or awareness are more likely to deliver better outcomes. By emphasizing a component process such as executive or ‘top-down’ control, the therapist and client are provided with a conceptual compass with which to navigate through the voyage of recovery. Chapter 5 addresses the question of individual susceptibility to addiction: if, indeed, drugs and gambling wins are such powerful rewards, why, ultimately, do not all but a small minority develop compulsive or addictive syndromes? This marks the transition from the more theoretical and research based chapters to content that is more directly relevant to the clinical or applied arena, although remaining grounded in a cognitive neuroscience paradigm.

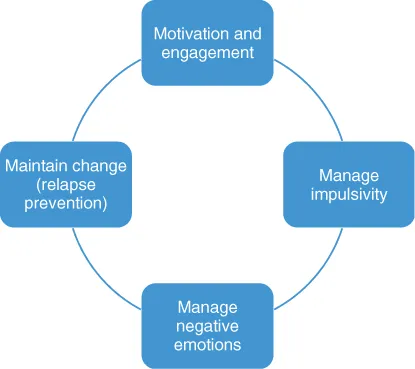

Most of the remainder of the book (Chapters 6, 7, 8 and 9) explicates key therapeutic phases from a cognitive control standpoint. The sequence that unfolds follows the ‘Four M’ structure (see Figure 1.1), which is the enactment of the CHANGE approach:

Motivation and engagement

Managing urges and craving

Mood management

Maintaining change.

Figure 1.1 The Four M Model. Clockwise, these are the four key stages.

Chapter 10 aims to summarize, integrate and look forward in the context of a vibrant research arena with major implications for the concept and conduct of cognitive therapy.

Discovering Cognition

Existing accounts of cognitive therapy for addiction have not accommodated findings that cognitive processes, in particular those deemed automatic or implicit, are influential in maintaining addiction, or indeed as a potential means of leveraging change. In cognitive parlance, these models do not legislate for ‘parallel processing’ across controlled or automatic modes, with the latter being largely overlooked. Simply put, existing accounts fail to address what is the hallmark of addiction: compulsive drug seeking behaviour that appears to occur with little insight and often in the face of an explicit desire for restraint. Moreover, existing cognitive therapy approaches do not accommodate findings that cognitive efficiency is often impaired in those presenting with addictive disorders, whether stemming from pre-existing or acquired deficiencies. The client has developed a strong tendency for preferential cognitive processing and facilitated behavioural approach in the face of impaired cognitive control. Failure to acknowledge this leaves the therapist and client in the dark about an important source of variance that is influential at all stages of the therapeutic journey.

The findings of Childress and her colleagues (2008), who used advanced functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) techniques to explore the neural signature of very briefly presented appetitive stimuli, are noteworthy. They found early activation of limbic structures such as the amygdala when the 22 participating abstinent cocaine addicts were shown subliminal, backward masked drug associated cues. A similar pattern was observed when covert sexual stimuli were presented. This design effectively eliminated the possibility of conscious recognition with backward masked exposure for a mere 33 ms, yet participants showed a clear pattern of activation in limbic structures implicated in reward processing. When tested with visible versions of these cues ‘off-magnet’ two days later, initial higher levels of brain activity in response to invisible cues was predictive of positive affective evaluation among the participants. As well as demonstrating the exquisite sensitivity of neural reward mechanisms to drug-related stimuli, these findings show that for habituated drug users the appetite for their drug of choice compares to powerful sexual drives: evidence perhaps that, for some, drugs are as good as, if not better than, sex. Further, Leventhal et al. (2008) found selective subliminal processing of smoking-related cues by nicotine-deprived smokers, again indicating non-conscious evaluative appraisal. It appears that, when exposed to significant cues, the brain makes up its mind very rapidly about what it wants. Extant theories (see, e.g., Marlatt, 1985; Beck, 1993) have difficulty in accounting for these cognitive events and processes, largely because information is processed at one level. Dual processing accounts, which form the basis of this text, have no such difficulty.

Implicit Cognition and Addiction

The definitive feature of implicit cognition is that ‘traces of past experience affect some performance, even though the influential earlier experience is not remembered in the usual sense—that is, it is unavailable to self-report or introspection’ (Greenwald and Banji, 1995, p. 4). These theorists illustrate the operation of implicit cognition with a generic example from experimental psychology. Participants are thus more likely to complete a word fragment or word stem using a word from a list to which they were previously casually exposed. Note that participants may not show explicit recall of the words but the effect of prior exposure nonetheless influences performance. The individual thus appears primed or predisposed to automatically generate a response that appears to evade introspection. This is, of course, precisely what is happening in the brains of the cocaine-addicted people referred to above: the drug-associated cues have acquired considerable emotional and motivational potency that assured them of preferential processing even the absence of conscious awareness.

In the addiction clinic, prior exposure to a vast array of appetitive stimuli, both focal and contextual, is the norm. Learning theory correctly charts the acquisition of conditioned behaviour, but is less able to accommodate cognitive processes, especially if these are implicit rather than manifest. Wiers et al. (2006) sought to clarify the scope of implicit cognition approaches in the addictive behaviour field by proposing three broad categories: attentional bias research, memory bias research and the study of implicit associations. Wiers et al. (2006) concluded that, at least in the populations of problem drinkers addressed in their article, there was an implicit bias towards the detection of alcohol-related stimuli. Following engagement of attention, subsequent information processing was shaped by implicit memory associations. Understandably, given their covert nature, these processes remain largely unseen and unheard by addicted people and their therapists. Moreover, their influence and expression is often masked in the sanitized environment of the treatment centre or clinic, thus creating a somewhat illusory sense of progress. For example, an individual who has just completed a detoxification procedure might explicitly predict their future progress, but implicit factors might improve predictive utility and thus influence the level and intensity of treatment subsequently received. Indeed, preliminary findings from Cox et al. (2002) indicated that alcohol-dependent patients who showed escalating levels of attentional bias to alcohol cues through the treatment episode were more likely to relapse. This raises the question of the feasibility and utility of modifying or reversing cognitive biases that will be addressed in Chapter 7. This finding was replicated by Garland et al. (2012), who found that attentional bias and cue-induced high-frequency heart-rate variability (HFHRV), assessed post treatment, significantly predicted the occurrence and latency to relapse at six-month follow-up in a sample of 53 people in residential care. This was independent of treatment condition (a 10-session mindfulness-based intervention and a comparable therapeutic support group) and after controlling for severity of alcohol dependence.

Implicit cognition might well be subtle but is also pervasive and can be detrimental for both therapeutic engagement and clinical outcomes. Accordingly, cognitive therapy needs to accommodate a broader concept of cognition in addiction, delineating a role for implicit processes in parallel with the more familiar focus on conscious deliberation and re-appraisal. This re-conceptualization is the basis for developing the innovative approaches to formulating and intervening with addictive and impulsive appetitive behaviours that will be addressed in this text. The theoretical framework and clinical strategies are thus derived from CBT but framed within a cognitive neuroscience paradigm. I shall describe how this emergent paradigm can augment existing therapeutics and also generate innovative techniques that directly target the core cognitive and behavioural mechanisms of addiction.

Cognitive control is compromised in addiction

In the context of overcoming addiction, cognitive control is concerned with maintaining recovery goals and monitoring progress in goal pursuit. In particular, managing addictive impulses that have become redundant, unwanted or risky is vital. Cognitive control, especially inhibition, thus forms a key component of the broader executive functioning necessary for self-regulation. Other components of this function, associated with the prefrontal cortex, include shifting strategies in response to changing task requirements and updating by monitoring of goal pursuit. These cognitive operations—shifting, inhibiting and updating—have emerged as relatively independent factors in experimental investigation of executive functioning Miyake et al., (2000). Impaired control over drug use by habituated users is of course a definitive feature of substance dependence and thus a rather obvious target for therapeutic intervention. Cognitive neuroscience findings provide confirmatory evidence for this. Chambers et al. (2009) reviewed evidence pointing to cocaine users, for example, showing impairments on several laboratory measures of impulse control such as having to withhold a well practised response or manifested in making riskier decisions. These deficiencies have been noted both under conditions of acute intoxication and also among abstinent restrained drug and alcohol users. Kaufman et al. (2003), for instance, using fMRI during a go/no go task, found significant cingulate, pre-supplementary motor and insular hyperactivity in a sample of 13 active cocaine users when compared with 14 cocaine naive...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About the Author

- Preface

- Chapter 1: The Tenacity of Addiction

- Chapter 2: Existing Cognitive Behavioural Accounts of Addiction and Substance Misuse

- Chapter 3: Core Motivational Processes in Addiction

- Chapter 4: A Cognitive Approach to Understanding the Compulsive Nature of Addiction

- Chapter 5: Vulnerability Factors In Addiction

- Chapter 6: Motivation and Engagement

- Chapter 7: Managing Impulses

- Chapter 8: Managing Mood

- Chapter 9: Maintaining Change

- Chapter 10: Future Directions

- Appendix: Self-Help Guide Six TipsA Pocket Guide to Preventing Relapse

- References

- Index