The Practitioner's Guide to Governance as Leadership

Building High-Performing Nonprofit Boards

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Practitioner's Guide to Governance as Leadership

Building High-Performing Nonprofit Boards

About this book

THE PRACTITIONER'S GUIDE TO GOVERNANCE AS LEADERSHIP

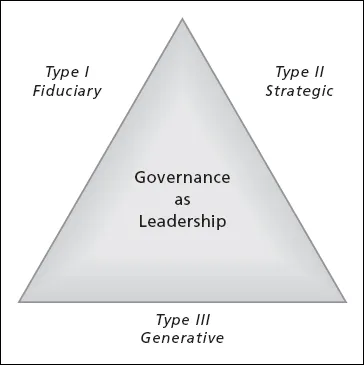

The Practitioner's Guide to Governance as Leadership offers a resource that shows how to achieve excellence and peak performance in the boardroom by putting into practice the groundbreaking model that was introduced in the book, Governance as Leadership. This proven model of effective governance explores how to attain proficiency in three governance modes or mindsets: fiduciary, strategic, and generative.

Throughout the book, author Cathy Trower offers an understanding of the Governance as Leadership model through a wealth of illustrative examples of high-performing nonprofit boards. She explores the challenges of implementing governance as leadership and suggests ideas for getting started and overcoming barriers to progress. In addition, Trower provides practical guidance for optimizing the practices that will improve organizational performance including: flow (high skill and high purpose), discernment, deliberation, divergent thinking, insight, meaningfulness, consequence to the organization, and integrity. In short, the book is a combination of sophisticated thinking, instructive vignettes, illustrative documents, and practical recommendations.

The book includes concrete strategies that can help improve critical thinking in the boardroom, a board's overall performance as a team, as well as information for creating a strong governance culture and understanding what is required of an effective CEO and a chairperson. To determine a board's fitness and help the members move forward, the book contains three types of assessments: board members evaluate each other; individual board member assessments; and an overall team assessment.

This practitioner's guide is written for nonprofit board members, chief executives, senior staff members, and anyone who wants to reflect on governance, discern how to govern better, and achieve higher performance in the process.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE GOVERNANCE AS LEADERSHIP MODEL

PREMISES

- First, nonprofit managers have become leaders. The days of the naïve nonprofit executive director leading a sleepy organization fueled by a few passionate “do-gooders” are long over, as stakeholders expect greater sophistication and leadership on the part of CEOs and their staff members.

- Second, board members are acting more like managers. Although board members are often admonished not to micromanage, many nonprofit board committee structures essentially invite board members into the senior staff’s domains. This occurs because the board structure tends to mirror that of the organization—for example, both will have committees in finance, government relations, development, and marketing—and nonprofits populate their boards and committees with professional experts in those same fields. “Constructed and organized in this way, boards are predisposed, if not predestined, to attend to the routine, technical work that managers-turned-leaders [premise one] have attempted to shed or limit” (4).

- Third, there are three modes of governance, all created equal. The authors recast governance from a “fixed and unidimensional practice to a contingent, multidimensional practice” (5) that includes fiduciary, strategic, and generative work (described in more detail later in this chapter) whereby the board provides oversight, foresight, and insight. Although each mode “emphasizes different aspects of governance and rests on different assumptions about the nature of leadership”, all three are equally important.

- Fourth, three modes are better than one or two. Boards that are adept at operating in all three modes will add the most value to the organizations they govern.

UNDERLYING ASSUMPTIONS

- Some official work is highly episodic. Boards meet regularly at prescribed intervals whether or not there is important work to be done; therefore, in order to fill air time, committees and staff members make reports and board members listen dutifully (or snooze). If board members are awake, in an effort to show diligence and attentiveness, they sometimes chime in with a question or two, but those questions are often operational in nature because the material on the table invites little else.

- Some official work is intrinsically unsatisfying. Some governance work is not episodic—that which involves overseeing and monitoring management must be done regularly and is critically important. Boards must, by law, meet duty of loyalty and care requirements to ensure that the organization is operating lawfully and its leaders are meeting standards of minimally acceptable behavior. But board members do not typically join nonprofit boards to “hold the organization to account” (Chait et al. 2005, 19) but instead because they identify with the mission and values of the organization. This disconnect can cause disappointment and disengagement.

- Some important unofficial work is undemanding. Just by meeting, boards create legitimacy for organizations. Further, because boards meet, management must prepare data and reports, which keeps management alert. But such passive roles are hardly motivating for board members.

- Some unofficial work is rewarding but discouraged. Because the rules about what is permissible board work (for example, fundraising, advocacy, and community relations) and what is not (for example, human resource management and program development) are often unstated or unclear, board members sometimes dive in only to be told to back off—that they are in management’s territory.

GOVERNANCE REFORM

THE THREE MODES OR MENTAL MAPS

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- List of Exhibits, Figures, and Tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- Chapter 1: The Governance as Leadership model

- Chapter 2: Getting Started and Gaining Traction with Governance as Leadership

- Chapter 3: Encouraging Critical Thinking in the Boardroom

- Chapter 4: Turning Your Board into a High-Performing Team

- Chapter 5: Creating a Governance-as-Leadership Culture

- Chapter 6: What Governance as Leadership Requires of Leaders

- Chapter 7: Measuring and Sustaining Governance as Leadership

- Epilogue

- References

- Acknowledgments

- The Author

- BoardSource

- Index