![]()

Part One

Enterprise as Complex System

—Frederick Winslow Taylor, The Principles of Scientific Management

![]()

Chapter 1

Introducing Agile Architecture

Agile. Architecture. Revolution. Them's fightin' words, all three of 'em.

Agile—controversial software methodology? Management consulting doublespeak? Word found in every corporate vision statement, where it sits collecting dust, like your grandmother's Hummel figurines?

Architecture—excuse to spend too much on complicated, spaghetti-code middleware? Generating abstruse paperwork instead of writing code that actually works? How to do less work while allegedly being more valuable? (Thanks to Dilbert for that last one.)

Revolution—the difference between today's empty marketing drivel and yesterday's empty marketing drivel? Key word in two Beatles song titles, one a classic, the other a meaningless waste of vinyl? What the victors always call wresting control from the vanquished?

No, no, and no—although we appreciate the sentiment. If you're hoping this book is full of trite clichés, you've come to the wrong place. We're iconoclasts through and through. No cliché, no dogma, no commonly held belief is too sacred for us to skewer, barbecue, and relish with a nice Chianti.

We'll deconstruct Agile, and rebuild the concept in the context of real organizations and their strategic goals. We'll discard architectural dogma, and paint a detailed picture of how we believe architecture should be done. And we'll make the case that the Agile Architecture Revolution is a true revolution.

Many readers may not understand the message of this book. That's what happens in revolutions—old belief systems are held up to the light so that people can see through them. Some do, but many people do not. For those readers who take this book to heart, however, we hope to open your eyes to a new way of thinking about technology, about business, and about change itself.

Deconstructing Agile

Every specialization has its own jargon, and IT is no different—but many times it seems that techies love to co-opt regular English words and give them new meanings. Not only does this practice lead to confusion in conversations with non-techies, but even the techies often lose sight of the difference between their geek-context definition and the real world definition that “normal” people use.

For example, ZapThink spends far too long defining Service. This word has far too many meanings, even in the world of IT—and most of them have little to do with what the rest of the world means by the term. Even words like business have gone through the techie redefinition process (in techie-speak, business means everything that's not IT).

It comes as no surprise, therefore, that techies have hijacked the word Agile. In common parlance, someone or something is agile if it's flexible and nimble, especially in the face of unexpected forces of change. But in the world of technology, Agile (Agile-with-a-capital-A) refers to a specific category of software development methodology. This definition dates to 2001 and the establishment of the Agile Manifesto, a set of general principles for building better software. The Agile Manifesto (from agilemanifesto.org) consists of four core principles:

1. Individuals and interactions over processes and tools. Agile emphasizes the role people play in the technology organization over the tools that people use.

2. Working software over comprehensive documentation. The focus of an Agile project is to deliver something that actually works; that is, that meets the business requirements. Documentation and other artifacts are simply a means to this end.

3. Customer collaboration over contract negotiation. Customers and other business stakeholders are on the same team, rather than adversaries.

4. Responding to change over following a plan. Having predefined plans can be useful, but if the requirements or some other aspect of the environment changes, then it's more important to respond to that change than stick obstinately to the plan.

In the intervening decade, however, Agile has taken on a life of its own, as Scrum, Extreme Programming, and other Agile methodologies have found their way into the fabric of IT. Such methodologies indubitably have strengths, to be sure—but what we have lost in the fray is a sense of what is particularly agile about Agile. This point is more than simple semantics. What's missing is the fundamental connection to agility that drove the Manifesto in the first place. Reestablishing this connection, especially in the light of new thinking on business agility, is essential to rethinking how IT meets the ever-changing requirements of the business.

How do techies know what to build? Simple: Ask the stakeholders (the “business”) what they want. Make sure to write down all their requirements in the proverbial requirements document. Now build something that does what that document says. After you're done, get your testers to verify that what you've built is what the business wanted.

Or what they used to want.

Or what they said they wanted.

Or perhaps what they thought they said they wanted.

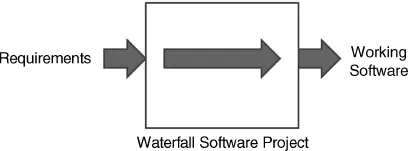

And therein lies the rub. The expectation that the business can completely, accurately, and definitively describe what they want in sufficient detail so that the techies can build it precisely to spec is ludicrously unrealistic, even though such a myth is inexplicably persistent in many enterprise IT shops to this day. In fact, the myth of complete, well-defined requirements is at the heart of what we call the “waterfall methodology, illustrated in Figure 1.1.

In reality, it is far more common for requirements to be poorly communicated, poorly understood, or both. Or even if they're properly communicated, they change before the project is complete. Or most aggravating of all, the stakeholder looks at what the techies have built and says, “Yes, that's exactly what I asked for, but now that I see it, I realize I want something different after all.”

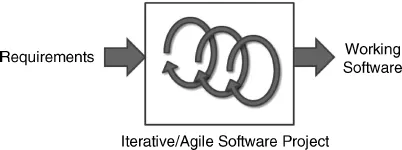

Of course, such challenges are nothing new; they gave rise to the family of iterative methodologies a generation ago, including the Spiral methodology, IBM's Rational Unified Process, and all of the Agile methodologies. By taking an iterative approach that involves the business in a more proactive way, the reasoning goes, you lower the risk of poorly communicated, poorly understood, or changing business requirements. Figure 1.2 illustrates such a project.

In Figure 1.2 the looped arrows represent iterations, where each iteration reevaluates and reincorporates the original requirements with any further input the business wants to contribute. But even with the most agile of Agile development teams, the process of building software still falls short. It doesn't seem to matter how expert the coders, how precise the stakeholders, or how perfect the development methodology are, the gap between what the business really needs and what the software actually does is still far wider than it should be. And whereas many business stakeholders have become inured to poorly fitting software, far more are becoming fed up with the entire situation. Enough is enough. How do we get what we really want and need from IT?

To answer this question, it's critical to understand that inflexibility is the underlying problem of business today, because basically, if companies (and government organizations) were flexible enough, they could solve all of their other problems, because no problem is beyond the reach of the flexible organization. If only companies were flexible enough, they could adjust their offerings to changes in customer demand, build new products and services quickly and efficiently, and leverage the talent of their people in an optimal manner to maximize productivity. And if only companies were flexible enough, their strategies would always provide the best possible direction for the future. Fundamentally, flexibility is the key to every organization's profitability, longevity, and success.

How can businesses aim to survive, even in environments of unpredictable change? The answer is business agility. We define business agility as the ability to respond quickly and efficiently to changes in the business environment and to leverage those changes for competitive advantage. The most important aspect of this definition is the fact that it comes in two parts: the reactive, tactical part, and the proactive, strategic part. The ability to respond to change is the reactive, tactical aspect of business agility. Clearly, the faster and more efficiently companies can respond to changes, the more agile they are. Achieving rapid, efficient response is akin to driving costs out of the business: It's always a good thing, but has diminishing returns over time as responses get about as fast and efficient as possible. Needless to say, the competition is also trying to improve their responses to changes in the market, so it's only a matter of time til they catch up with you (or you catch up with them, as the case may be).

The second, proactive half of the business agility equation—leveraging change for competitive advantage—is by far the most interesting and powerful part of the story. Companies that not only respond to changes but actually see them as a way to improve their business often move ahead of the competition as they leverage change for strategic advantage. And strategic advantages—those that distinguish one company's value proposition from another's—can be far more durable than tactical advantages.

Building a system that exhibits business agility, therefore, means building a system that supports changing requirements over time—a tall order. Even the most Agile development teams still struggle with the problem of changing requirements. If requirements evolve somewhat during the course of a project, then a well-oiled Agile team can generally go with the flow and adjust their deliverables accordingly, but one way or the other, all successful software projects come to an end. And once the techies have deployed the software, they're done.

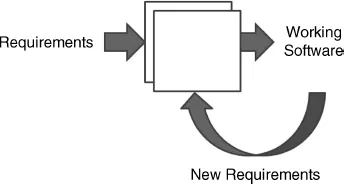

Have a new requirement? Fund a separate project. We'll start over and include your new requirements in the next version of the project we already finished, unless it makes more sense to build something completely new. Sometimes techies can tweak existing capabilities to meet new requirements quickly and simply, but more often than not, rolling out new versions of existing software is a laborious, time-consuming, and risky process. If the software is commercial off the shelf (COTS), the problem is even worse, because the vendor must base new updates on requirements from many existing customers, as well as their guesses about what new customers will want in the future. Figure 1.3 illustrates this problem, where the software project represented by the box can be as Agile as can be, and yet the business still doesn't get the agility it craves. It seems that Agile may not be so agile after all.

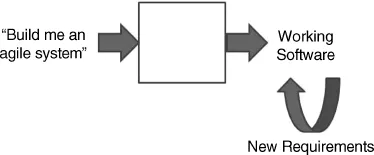

The solution to this problem is for the business to specify its requirements in a fundamentally different way. Instead of thinking about what it wants the software to do, the business should specify how agile it expects the software to be. In other words, don't ask for software that does A, B, C, or whatever. Instead, tell your techies to build you something agile.

We call this requirement the meta-requirement of agility—a meta- requirement because agility applies to other requirements: “Build me something that responds to changing requirements” instead of “Build me something that does A, B, and C.” If we can build software that satisfies this meta-requirement, then our diagram looks quite different (see Figure 1.4).

Because the software in Figure 1.4 is truly agile, it is possible to meet new requirements without having to change the software. Whether the process inside the box is Agile is beside the point. Yes, perhaps taking an Agile approach is a good idea, but it doesn't guarantee the resulting software is agile.

Sounds promising, to be sure, but the devil is in the details. After all, if it were easy to build software that responded to changing requirements, then everybody would be doing it. But there's a catch. Even if we built software that could potentially meet changing requirements, that doesn't mean that it actually would—because meeting changing requirements is part of how you would use the software, rather than part of how you build it. In other words, the users of the software must actually be part of the agile system. The box in Figure 1.4 doesn't just represent software anymore. It represents a system consisting of software and people.

Architecting Software/Human Systems

Such software/people systems of systems are a core theme of this book. After all, the enterprise—in fact, any business that uses technology—is a software/human system. To understand Agile Architecture, it's essential to understand how to architect such a system.

Software/human systems have been with us as long as we've had technology, of course. A simple example is a traffic jam. Let's say you're on the freeway, and an accident in the opposing direction causes your side to slow down. Not because you want to, of course. You're saying to yourself that you really don't care to rubberneck. You'd rather keep moving along. But you can't, because the person ahead of you slows down. And they're slowing down because the person ahead of them is.

What's ...