- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Root Genomics and Soil Interactions

About this book

Fully integrated and comprehensive in its coverage, Root Genomics and Soil Interactions examines the use of genome-based technologies to understand root development and adaptability to biotic and abiotic stresses and changes in the soil environment. Written by an international team of experts in the field, this timely review highlights both model organisms and important agronomic crops. Coverage includes: novel areas unveiled by genomics research basic root biology and genomic approaches applied to analysis of root responses to the soil environment. Each chapter provides a succinct yet thorough review of research.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Genomics of Root Development

Introduction

Roots: Rising from the Underground

Because of the different roles the root system plays in overall plant growth, root architecture is a fundamental aspect of plant growth and development. The root system especially acquires water and nutrients from the soil, anchors the plant in the substrate, synthesizes hormones and metabolites, interacts with symbiotic microorganisms, and insures storage functions. In light of these characteristics, more and more breeders turn their attention to this underground organ in order to increase yield. This requires a better understanding of the relation of this part of the plant with the environment and of its highly adaptive behavior (Lynch 2007; Gewin 2010; Den Herder et al. 2010).

Within the angiosperms, major differences in root architecture between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants exist. Dicots develop a tap root system composed of a main primary root, already formed during embryogenesis, which grows vertically into the soil and gives rise to the emergence of numerous lateral roots extending the surface area. Monocots have a fibrous root system in which the embryonic primary root is only important for the early development of the plant (Feix et al. 2002) and in which an extensive postembryonic shoot-born root system is formed later on. Very little is known about the genetic and molecular mechanisms involved in the development and architecture of the root system in major crop species, generally monocotyledonous plants. Lack of insight is certainly a consequence of the difficulty to access and observe this organ in its natural habitat, namely the soil. Moreover, and probably because of this hidden character, the root has been neglected for a long time in crop improvement and in agricultural approaches aiming at increasing shoot biomass. Nevertheless, while most of the work has been done on Arabidopsis thaliana, the awareness of the importance of the root system in modulating plant growth, together with progress in sequencing and new molecular techniques, has caused renewed interest in understanding molecular mechanisms in crop species (Hochholdinger and Zimmermann 2009; Coudert et al. 2010).

In the scope of root development and its interaction with the soil, in this chapter, we propose to focus on the mechanisms involved in root branching, which is a major determinant of root system architecture. The plasticity of the root system represents indeed an important potential for plants, being sessile organisms, to adapt to the heterogeneity of their environment. The soil is a complex mixture of solid, gaseous, and liquid phases, wherein nutrients are unequally distributed. Plants have therefore developed a highly sophisticated regulatory system to control their root architecture, in response to environmental cues, by modulating intrinsic pathways to optimize their root distribution in the soil and consequently guarantee an optimal uptake of nutrients necessary for growth and development (reviewed in Croft et al. 2012).

Primary Root Structure and Development: Lessons from the Arabidopsis Model

Branching of roots occurs through the development of new meristems inside the primary parent root. We therefore first discuss briefly the structure and development of the primary root in Arabidopsis, the model species in which major insights were obtained, thanks to its simple root architecture (Dolan et al. 1993; Malamy and Ryan 2001; Scheres et al. 2002; Casimiro et al. 2003; Casson and Lindsey 2003; Ueda et al. 2005; Iyer-Pascuzzi et al. 2009; Peret et al. 2009).

The root can be divided in three main zones. The most distal, at the tip of the root, is the meristematic zone, where the so-called initial cells give rise to the tissues constituting the root. The initial cells are kept in an undifferentiated state by the neighboring quiescent center (Van den Berg et al. 1997), a mitotically less active region, composed of few central cells in Arabidopsis. Higher up, in the elongation zone, cells progressively stop dividing and start to expand longitudinally. Finally, cells differentiate and acquire their final cell fate in the maturation zone (Truernit et al. 2006), which can be recognized by the appearance of the anatomical structures of the vascular tissues.

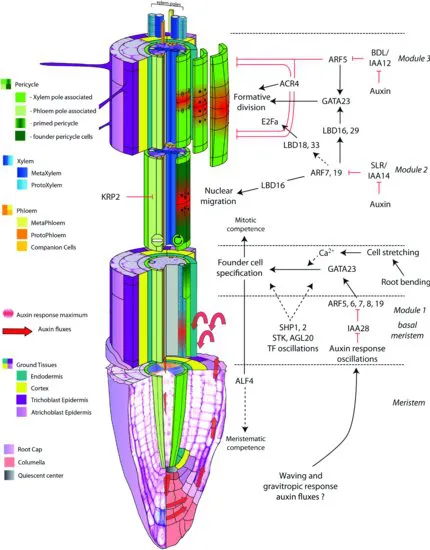

Distinct cell types are then composing the mature root (Figure 1.1). The outer layers, endodermis, cortex, and epidermis are organized in concentric layers and present a radial organization toward the longitudinal axis of the primary root (Dolan et al. 1993). The epidermis, which is the outermost layer of the root, is in direct contact with the soil and is often designated as rhizodermis. It is composed of two populations of cells: one producing root hairs and the other nonhair cells (Schneider et al. 1997). The root hairs are responsible for the major part of the nutrient uptake from the soil (Muller and Schmidt 2004) and also play other important roles such as the initial contact with certain symbiotic partners (Gilroy and Jones 2000; Perrine-Walker et al. 2011). Cortex and endodermis constitute the ground tissue and are derived from one single initial cell in Arabidopsis (Dolan et al. 1993; Scheres et al. 1994). The stele is situated internal to these layers and comprises the vascular cylinder, consisting of two bilateral poles of xylem alternating with two bilateral poles of phloem separated by procambium cells (Dolan et al. 1993). The stele also contains a heterogeneous layer, the pericycle, interfacing the vascular cylinder and the outer layers, playing a predominant role in root architecture and root branching (Parizot et al. 2008).

FIGURE 1.1 Structure of the primary root and different steps of lateral root initiation. See the text for detailed description.

Root Branching

In dicotyledonous plants, such as Arabidopsis, elaboration of the root system occurs postembryonically by the formation of numerous secondary roots from the primary root that was formed during embryogenesis. These new roots are comparable to the primary root in structure and will be able to reiterate the branching process by in turn initiating tertiary roots. Roots of second, third, and higher order are defined as lateral roots. The plant can also produce adventitious roots, which initiate mostly at the base of the hypocotyl. Different markers related with cell identity show a similar pattern in the primary and lateral roots (Malamy and Benfey 1997b; Laplaze et al. 2005), indicating the possibility of a common developmental pathway. This hypothesis is supported by a high number of mutants affected in genes involved in root patterning, such as SHORTROOT, SCARECROW, and LONESOME HIGHWAY, showing similar defects in the primary and lateral roots (Helariutta et al. 2000; Wysocka-Diller et al. 2000; Parizot et al. 2008; Lucas et al. 2011). However, some differences can be observed in the behavior of the primary and the lateral roots toward external cues such as gravity and substrate nutrient concentrations (Zhang and Forde 1998; Mullen and Hangarter 2003; Bai and Wolverton 2011). A mutation in the gene MONOPTEROS impairs the apical–basal pattern formation of the embryo and leads to plants lacking a primary root, but that are still able to generate adventitious roots (Berleth and Jurgens 1993; Przemeck et al. 1996), indicating that early pathway(s) required for the embryonic formation of a root meristem are not required postembryonically. Also, a mutation in the gene WOODEN LEG has a major effect on the primary root development, with the suppression of the phloem elements and a drastic reduction in lateral root initiation (LRI), but does not affect the formation and branching of adventitious roots (Kuroha et al. 2006).

The monocots, such as maize, form different types of roots: primary, seminal, and adventitious roots, which can all form lateral roots. These root types also present similarities in their structures. However, mutants missing only a subset of these root types have been isolated, indicating that at least a part of the genetic program necessary for their formation is root-type specific (Woll et al. 2005; Hochholdinger and Tuberosa 2009).

Lateral Root Initiation

In Arabidopsis and most other dicotyledonous plants, lateral roots are formed from a restricted number of pericycle cells located in front of the xylem poles (Figure 1.1). The pericycle is a heterogeneous tissue composed of quiescent cells adjacent to the phloem poles and cells competent for LRI in front of the xylem poles (Beeckman et al. 2001; Parizot et al. 2008). Therefore, this layer presents a radial bilateral symmetry along the primary root, which reflects the diarch symmetry of the more internal vascular bundle as compared to the surrounding concentric radial layers of the outer tissues. The subpopulation of pericycle cells adjacent to the xylem poles can be considered as an extended meristem, as they conserve the ability to divide after leaving the root apical meristem (in contrast to the cells in front of the phloem poles), and give rise to the formation of a new organ (Beeckman et al. 2001; Casimiro et al. 2003). Although up to three adjacent pericycle cell files associated with each xylem pole are dividing during lateral root formation, cell lineage experiments have shown that only the central cell file will contribute significantly to the formation of the lateral root primordium (Kurup et al. 2005).

The first pericycle cell divisions that will give rise to a lateral root (i.e., formative divisions) can only be detected several millimeters above the primary root meristem, whereas in the lower part of a region named developmental window (Dubrovsky et al. 2006), it has been demonstrated that a subset of pericycle cells is already specified for LRI in a zone situated immediately above the primary root apical meristem, the basal meristem (De Smet et al. 2007; De Rybel et al. 2010b). The phytohormone auxin is most likely the signal triggering this priming, as auxin response recorded using the auxin response marker DR5 shows pulsations in the protoxylem cells of the basal meristem with a periodicity that can be correlated with the initiation of new lateral roots (Ulmasov et al. 1997; De Smet et al. 2007; De Rybel et al. 2010b; Moreno-Risueno et al. 2010). Up to now, different hypotheses have been proposed to explain the origin of these oscillating auxin response maxima in the protoxylem cells, and no consensus has been reached yet. Also the mechanism by which this auxin signal in the protoxylem cells is translated into the specification of founder cell identity in the neighboring pericycle cells is still unknown. Nevertheless, this intrinsic mechanism can be overruled, as the application of auxin on mature parts of the root above the basal meristem is still able to trigger LRI (Himanen et al. 2002), further reflecting the high plasticity of the root system.

The first morphological event preceding the division of two adjacent pericycle founder cells is the simultaneous migration of their nuclei to their common cell wall (De Smet et al. 2007). This migration is followed by an asymmetric anticlinal division of the pericycle cells, resulting in the formation of a core of small daughter cells flanked by larger cells (Dubrovsky et al. 2000). Successive anticlinal and periclinal divisions give rise to a lateral root primordium. Further divisions and elongation of the primordium cells result in the formation of a fully autonomous root, with a meristem similar to that of the primary root (Malamy and Benfey 1997b; Dubrovsky et al. 2001). Although the place of LRI differs between plant species, early patterning of the primordium is quite conserved (Casero et al. 1995; Malamy and Benfey 1997bb). The frequency of LRI in the Arabidopsis primary root can fluctuate in response to tropic and/or mechanical stimuli (De Smet et al. 2007; Ditengou et al. 2008; Laskowski et al. 2008; Lucas et al. 2008a). For example, a gravitropic stimulus applied to seedlings induces a lateral root at the place where the root bends to recover its normal growth angle (Lucas et al. 2008a).

Genomics of LRI

Most of the work on root development focused on the analysis of single mutants and allowed the discovery of many processes involved in the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Genomics of Root Development

- Chapter 2: The Complex Eukaryotic Transcriptome: Nonprotein-Coding RNAs and Root Development

- Chapter 3: Genomics of Auxin Action in Roots

- Chapter 4: Cell-Type Resolution Analysis of Root Development and Environmental Responses

- Chapter 5: Toward a Virtual Root: Interaction of Genomics and Modeling to Develop Predictive Biology Approaches

- Chapter 6: Genomics of Root Hairs

- Chapter 7: The Effects of Moisture Extremes on Plant Roots and Their Connections with Other Abiotic Stresses

- Chapter 8: Legume Roots and Nitrogen-Fixing Symbiotic Interactions

- Chapter 9: What the Genomics of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis Teaches Us about Root Development

- Chapter 10: How Pathogens Affect Root Structure

- Chapter 11: Genomics of the Root–Actinorhizal Symbiosis

- Chapter 12: Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria and Root Architecture

- Chapter 13: Translational Root Genomics for Crop Improvement

- Index

- Advertisements

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Root Genomics and Soil Interactions by Martin Crespi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Botany. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.