![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Context of Innovation

Why Everyone Wants Innovation but No One Wants to Change

Our firm was in a bit of a slump. We had a hugely successful product a few years ago, but now we were facing increasing pressure to come up with the follow-up product, the next big thing. One day the big boss called the team into the office and said,

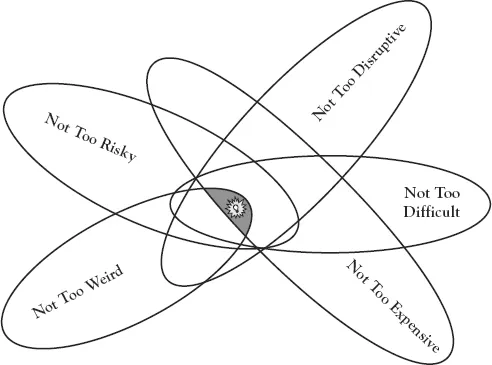

“People, this is serious. It has got to be big! Look, I really need you to think outside the box—don’t constrain yourselves! Listen, I really want you to push the boundaries way out there on this one; remember, we’re talking blue-sky this time—a real breakthrough!”

So the team and I ran off, excited, and “box be damned,” we started thinking big. Just two sleepless weeks later, we had found it! We had come up with a great idea! So we set up a meeting to present it. In the meeting the boss listened for a while, asking a question or two. Then he let out a loud sigh and said,

“Hmm ... this looks expensive ... I mean, I appreciate how you people are thinking outside the box, but I hope you realize that we have a business to run here. Now remember that I do want you to keep thinking outside the box, but can you try to make sure that it’s not quite so expensive?”

So off we went to find another idea. About a week later we had come up with a less expensive idea that was even better. In the big meeting, the boss again asked just a question or two before he sighed and said,

“This looks complicated. I mean I appreciate how you people are thinking outside the box, but I hope you realize that we’ve got to be able to make this in our plant. I want you to keep thinking outside the box, but can you try to make sure that we can at least manufacture the thing in-house?!”

Next idea: “Too disruptive!”

Next idea: “Too risky!”

Next idea: “Too weird!”

After about six months of this, my team finally came up with the idea, one that we believed met every requirement the boss had given us. When we presented it to him, he didn’t even bother asking questions. Ten minutes into our spiel, he became agitated and said,

“This looks puny! I mean, I asked you people to think outside the box, and all you can bring me is this puny idea? What’s wrong with you people? Don’t you know how to be creative?”

As the rate of product and service innovation speeds up, so does the need for a meaningful competitive response. For executives, managers, and employees in many organizations, this “innovation imperative” has been successfully met. Witness the many amazing innovations heaped upon us in the last ten years, from cell phones to smart phones, from MP3s to online television, from self-balancing scooters to private space travel.

This constant stream of newness left me curious about how executives and managers lead the aspiring innovators in their organizations on a path to successful innovation, so I started to ask them. In my executive programs, workshops, and consulting engagements, I began to ask people to tell me the stories of how innovation was managed and led in their organizations. Invariably they tell me surprising stories like the one you just read.

I have heard these tales of frustration again and again from people in organizations big and small across a wide swath of industries and in countries around the globe. To be fair, the story doesn’t always point the finger at the boss as the lead knucklehead in torpedoing innovation efforts. Variations of the story implicate customers, clients, partners, suppliers, colleagues, and even the team itself.

Although I occasionally came across people who have more positive things to say, their stories tend to portray successful innovation in their organizations as isolated incidents or accidents of fate. So even though I had started out wondering how managers lead successful innovation, the impassioned frustration I had heard from thousands of people led me to a different set of questions, the ones at the heart of this book: Why do people in organizations seem to work overtime ignoring, undermining, blocking, maiming, and killing the innocent, well-intentioned, and sometimes even great ideas in their organizations? Why do they so often act as if creative people must be stopped? And What can we do to change these behaviors so that innovation has a better chance to succeed?

Why Does Innovation Fail?

There are countless variations on the familiar story of innovations being torpedoed even before they are launched, or of being launched with great fanfare only to sink without a trace once they hit the marketplace. Here are just a few from my personal experience:

- In an experiment aimed at improving its ability to innovate, a large consumer products company known for lean operations, low prices, and derivative products invents a breakthrough product that can launch it to the lead in a large and extremely competitive segment of the industry it serves. Before it can get the product through its development process, the firm lays off all of the people involved with the project, citing financial pressures. The project never regains momentum and is cancelled.

- Because they have an intimate understanding of their clients’ businesses, the partners of an accounting consultancy agree to start an innovation practice aimed at helping clients grow their businesses. The new practice stalls when the partners, despite their earlier enthusiasm, refuse to refer their clients to the innovation consultants. The partners want proof that the innovation methods will work without creating any risk for their clients. Without clients to prove or improve their methods, the new practice languishes and eventually shuts down.

- A part-time inventor has the idea to invent a digital picture frame ten years before it becomes a household product. He starts working on the project until an expert from the electronics industry he meets tells him it’s a dumb idea that will be too expensive and not even possible. The inventor gives up all interest in pursuing the project any further.

- A university seeking to increase the rate at which technologies are moved out of the lab and into commercial products undertakes a significant effort to build, house, and fund an organization for the purpose. Successful entrepreneurs avoid the place, saying that the university researchers have no idea what makes an idea a potential commercial success; the university researchers avoid the place, saying that the entrepreneurs have no imagination and care only about making money from their research.

- Consistent with its mission, a performing arts organization seeks to expand its ability to offer more modern and controversial works. After a multiyear capital campaign, it is able to build the larger and more flexible space it needed to support its goal. A few years after moving into the new space, the organization finds itself paying for the expansion by performing even more standards and commercial works than before out of a need to draw larger audiences than the modern, controversial pieces attracted.

On the surface, these stories have little in common beyond the theme of innovation failure. The contexts are very different from one another, the players are diverse, and in each case the causes of the failure seem to be distinctive if not difficult to pinpoint. Yet with the right conceptual tools, I believe we can analyze both failures and successes in innovation efforts. We can discover the common themes that run through stories like these, and in the process derive powerful lessons for how to increase our own chances of success.

Six Perspectives on Innovation

To understand why innovation fails so often, I began combing through the enormous quantity of books, articles, and cases devoted to innovation and creativity. I quickly found, as you may have also, that these writings seemed to be talking about innovation and related concepts from wildly divergent and often unrelated perspectives. Worse, the perspectives offered by one thinker or researcher conflicted with the insights of others. However, after years of initial confusion, a pattern emerged. There were, I discovered, six basic perspectives on innovation and what impedes it.

One set of books had as their ideology, or basic theory, the unsurprising idea that the basic requirement for innovation is creative ideas. Failures of innovation were therefore failures of ideas: individuals either did not generate good enough ideas or didn’t recognize their good ideas for what they were and chose an inferior one. Intuitively this makes sense—without a good idea to base it on, innovation won’t happen. To meet this challenge, you simply need to train people to use the tools and processes that help them “think different,” and this will enable them to become better at generating and recognizing good ideas.

A second group of thinkers found this individual-centric view of innovation entirely unconvincing. For them, innovation fails because of a dysfunction in the emotional and cultural climate of the group undertaking an innovation initiative. Supported by experimental research and documented cases, they described precisely the emotional dynamics and social environments that reliably kill, among other things, the engagement, risk-taking, and creative expression necessary for innovation. This perspective could be summed up as even if you have a roomful of da Vincis, the group’s social climate will determine whether an innovation succeeds. The prescription that follows from this diagnosis is equally clear: fix the group’s climate, and you will fix innovation. At this point I had identified two compelling kinds of explanation for the failure of innovation. I probably should have quit while I was ahead. It turned out there were several more to come.

A third perspective came from writers who took an organization-centric approach. These authors convincingly showed how a firm’s strategy, organizational structure, and access to resources were critical to successful innovation. If a firm doesn’t have the intention of innovating and moving beyond its past laurels, or if it doesn’t have a structure that allows for the free movement of new ideas, or if it doesn’t have the human, monetary, or other resources to expend on developing an idea, then it’s unlikely to be a fertile source of innovation. With an eye to big bureaucratic organizations like governments, educational institutions, and commodity producers in mature markets, the case seems easy to make: the problem of innovation is the problem of organizing people in a way that won’t kill it.

A fourth set of writers widened the analytical lens even more and approached the problem of innovation from a market economics perspective. For them, innovation fails when a firm competing among a group of rivals in an industry fails to produce an innovation that the customers in that market are willing to adopt. In this perspective, innovation fails when buyers do not adopt a new offering because they fail to see the utility and value of it. If people don’t adopt the idea, you may be able to call an idea “creative,” but you cannot call it an innovation.

A fifth set of writers opened the lens still wider, emphasizing the social values of the individuals and groups for whom an innovation is intended. Their basic proposition is that an innovation cannot succeed if a society does not see its ideals and aspirations embodied in it. As we will discuss later, a good example of this argument is human cloning, or creating a human directly from the DNA of another human. Plants and animals have been successfully cloned in the past, so we might assume that human cloning is technologically possible and arguably would have certain benefits. However, most societies around the world ban the practice on the grounds that it is morally and ethically repugnant. Clearly, innovations that are discordant with societal values are unlikely to succeed.

Finally, a sixth perspective approached failures of innovation from a technological perspective. The premise was simple: some things are just hard to do. It is hard to keep the body alive during brain surgery, to derive energy from the splitting of uranium atoms in a controlled and safe way, or to plug an oil leak fifty miles offshore and one mile beneath the surface of the ocean. This perspective makes a strong case for the view that for an innovation to succeed, it has to be technologically feasible. In this view, the way to avoid failure is to advance our understanding and control of matter and energy through the use of science and technology. In other words, innovation is exactly what we already know as R&D.

Too Much of a Good Thing?

The table summarizes the six perspectives on innovation I have described. All six agree that there are interventions that can make innovation more likely to succeed. The only trouble is that each perspective assigns fault for failures in innovation to a different set of causes and therefore recommends a different set of “fixes.”

Six Perspectives on Innovation

| Why Does Innovation Fail? | How Do We Fix Innovation? | Focus of Analysis |

| Individuals do not “think different”; they don’t generate enough good ideas, the raw material of innovation. | The individual must improve his or her cognitive ability to recognize and generate relevant new ideas. | The individual |

| Groups allow negative emotions to derail the process of evaluating and implementing new ideas. | The group’s processes and cu... |