![]()

Chapter 1

Change Is Inevitable, Growth Is Optional

Charles Dickens may have been the first supply chain industry analyst. Back in the 1800s, he wrote: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair....” Sound like another day in the life of a supply chain professional? Nowhere in industry is there a profession that has so much volatility, variability, and certain uncertainty. And nowhere in a company is an organizational structure (you may say function) that has as many levers on free cash flow, return on invested capital, and shareholder value. Quite simply, if you can't ship it, you can't bill it. Create, Market, and Sell all you want; but if you can't Source, Make, and Deliver it, it will never be capital or revenue to Invest, Measure, and Value. And the total cost it delivers (landed) determines its profitability.

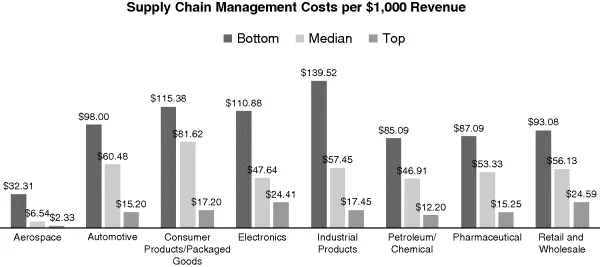

And, as Dickens's novel is titled A Tale of Two Cities, so, too, we can call the supply chain a tale of two cities; cities that we can call “Leaders” and “Laggards” with a channel of doubters between them. For nearly 25 years, I have been leading most of my presentations with a graphic of industry benchmarks (see Figure 1.1). Don't worry about the date. It doesn't matter. While I ask my friends at APQC to refresh the data each year, even though the raw numbers may vary a bit, the gap between top, median, and bottom percentiles has remained the same. “Best-in-class” companies outperform their median competitors with more than a 50 percent cost advantage! And the gap between the Leaders and Laggards is even more significant.

Why is it that despite advances in performance improvement methodologies, tools, technologies, and education, lagging and even median performers haven't been able to close the gap on supply chain costs? As we will see in later chapters, the gap among other metrics can be close. But, in the total cost metric, there remains a significant gap—a gap that has been sustained for more than 25 years. It begins with supply chain complexity and trade-offs. To excel in total, one must be excellent in total. There are too many cost trade-offs between time, mode, distance, speed, service, and other attributes of the supply chain (to name a few) that to excel in all requires a high level of integration, education, systems, and commitment that most companies have not been willing or able to make. Companies that are unwilling to transform their operations to adopt best practices and adapt to a changing marketplace will continue to inhabit the city of Laggards.

Throughout this book, we'll explore why that is, but, if companies think it's size, cost, or level of financial investment, they are wrong. Working again with APQC (they maintain extensive open standards research on industry metrics and benchmark data), we have not been able to find any correlation between performance and revenue or investment. Companies of all sizes, level of investment, and industries have been able to achieve high performance results sustainable over time by continuous improvement and best practices adoption. And, similarly, companies with what appear to be brand and financial equity populate the median and even the Laggards' metrics. So why is this? Why does such a gap exist?

The good news about being considered an industry visionary is that you can use the same slides for 25 years and they will still be current. The bad news is that many companies’ operations processes and systems have not progressed significantly in those same 25 years despite the fact that they have probably invested millions in enterprise applications (i.e., enterprise resource planning, or ERP) and systems integration. And it's not that the world hasn't changed in that time; au contraire, the world has seen more change in the past 25 years than in the past 250 years. It just seems that organizational paradigms (i.e., culture) are defined in such a way that it is very difficult to move an organization, let alone transform it, without real leadership from the head office.

Well, it doesn't have to be that way. And while I'd like to think the executives at the top are reading this to drive their organizations forward, this is a road map for everyone in the organization. While it really helps to have transformation driven from the top, we cannot necessarily wait for or expect that every senior executive will be driven toward operations excellence or necessarily understand what it is. You, regardless of your rank in the company, can garner top management commitment more easily than you think, and in the coming pages we will explore not only how, but why.

Globalization Changes the Game

Globalization is not only changing the competitive landscape but also the way companies will compete and collaborate with one another. Yes, collaborate. For, if we don't collaborate to eliminate waste across all dimensions, the twenty-first century may be the beginning of the last millennium. From new product development, commercialization, marketing, and sales to how you plan, source, make, and deliver your products in a sustainable manner, to capital acquisition and deployment, cost structure and performance, all functions of the organization contribute to increasing shareholder value.

Before I began my business and research career, I was a theology and English teacher. As an English major in college, one of the first things I learned was the definition of research: “To steal from one is plagiarism; to steal from many is research!” As an industry researcher, I have been “stealing” practices, best and worst, from many sources, colleagues, and companies that I have engaged throughout the years, heard present at numerous industry conferences, attended executive programs, and occasionally shared war stories over a beer. Of course, I will acknowledge their contribution to my research base accordingly.

What's interesting, though, is how few people have connected the dots over the years. When I was at Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), I had the opportunity to work with Peter Senge, author of The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of The Learning Organization,1 and his colleagues at Innovation Associates (founded by Charlie Kiefer), especially Michael Goodman and Bill Latshaw. At DEC, we were developing the “Digital Logistics Architecture.” We were using Senge's teaching in system dynamics and utilizing the Beer Game to teach the conundrums of supply chain. That project brought us all together. More about the Beer Game in Chapter 3.

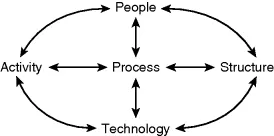

It was while working with Senge and his colleagues that systems thinking really began to have an impact on the analysis of all of the industry practices I was “stealing.” It's not necessarily the practices, advances, and changes individually that bring revelation and transformation. It's how all of the end-to-end activities, as a system, impact behavior. Change is a dynamic system of people, processes, and technology impacted by organizational structure and activity (see Figure 1.2).

That is where the impact of books like Thomas Friedman's The World Is Flat is realized.2 It's not the individual impact of the 10 “flatteners” that Thomas Friedman speaks about in his book; it's the dynamic convergence of those flatteners that changes the world. What's important about his work is that several billion new consumers and tens of thousands of new businesses are entering the global commerce consumption and competitive markets.

All of those new consumers and competitors have real-time global communication and commerce capabilities at very low cost—virtually! New software applications that leverage limitless computing power, what (Gordon) Moore's Law (Intel, early 1990s) states: “Every 18 months computing power doubles and its price drops in half,” is being developed more rapidly and inexpensively due to open source code collaboration, business process management, cloud technology deployment, and business process management software tools. And it's a challenge to the electronics supply chain... computers have a shorter shelf life than a gallon of milk!

Communicating on a global basis is as common as talking across the fence to your neighbor; as Bill Gates in the early 1990s said, “We'll have infinite bandwidth in a decade's time.” What he didn't forecast is how inexpensive it would be. I communicate with colleagues all over the world virtually for free using Skype. Using “tele-presence” technology from companies such as Cisco and Polycom, I recently sat “across” the table in a client meeting in Decatur, Illinois, and from colleagues in London, England, virtually. Toss in the fact that it can all be done through your personal communication device (including all commercial broadcasts), wirelessly, and anywhere, anytime, and well, yes, Tom Friedman, the world is not only flat but always on and in HD 3D. It won't be long before “telepresence” is holographic; thank you, Princess Leia.

However, of great importance to you is not only the emergence of a flat world paradigm changing the playing field; it's changing the game and how your company will compete in the twenty-first century. Companies are unlocking the value of their supply chains, outsourcing more and more noncore processes (not just for cost but for flexibility and agility), deploying more of their sales and marketing operations as well as production to the geographic point of the most profitable response, and leaning themselves into rapidly adapting, customer-responsive global competitors that see your business as their lunch. Innovation is the breakfast of champions, market leadership is for dinner, and dessert is increased shareholder value. Apple, for example, traditionally tops Gartner's Top 25 Supply Chains list, and they outsource just about all of their supply chain operations' execution capability.

Paradigms Drive Organizational Behavior and Culture

Transforming your organizational paradigm to a customer-responsive smart supply network (see accompanying “The Smart Supply Network”) is the new strategic imperative for competing in the years ahead. While we hear of some successes, the major challenges to implementation are managing change and leveraging technology to empower your people to capitalize on the opportunities that a new world economy creates. Companies must adapt and tech-enable their business processes to the new global playing field to create game-changing strategies for market leadership against new and fierce global competitors, or be voted off the island. And it doesn't have to cost millions or require an army of consultants and integrators. You have the capability within your own company. Why not “unleash the hounds”?

Everett Rogers, in his 1962 book The Diffusion of Innovations (which has been widely adapted), suggests that the degree to which an innovation (something perceived as new or a change) is perceived (by its opponents) as being better than the idea it supersedes has a direct impact on the likelihood of adoption.3 What that really means is “no pain, no gain.” Change isn't easy. It's hard work. People aren't likely to accept a change to their comfort zone unless the innovation is perceived as being vastly better than the status quo.

One of my good friends and professional colleagues is Rick Blasgen. We first met when he was a planner at Nabisco and I was at Information Resources (IRI). Blasgen is now the CEO of the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP), which was called the Council of Logistics Management (CLM) when I joined. At the 1997 CLM Annual Global Conference in Chicago, Blasgen presented on supply chain management at Nabisco.

One of the major barriers to Nabisco's supply chain transformation, he said, was that the “company was mired in a successful way of doing business....”

Think about that. Your first reaction is to say, “Don't fix it if it ain't broke.” Status quo, especially successful status quo, creates a comfort zone that is difficult to change. But, as the market around the company changes, as Blasgen pointed out in his presentation, if the company is not adaptive to change, its success can be fleeting.

The reality is that the organization creates the comfort zone, and it's called culture. The first step in any transformation or even a project initiative is to understand the culture. Transforming operations means transforming the culture. It's also the hardest thing for people to communicate. Visiting hundreds of companies over the years and asking people to describe their culture, I get hundreds of blank stares first, followed by deep thought, followed by some glib description of emotional attributes like enthusiastic, regimented, highly disciplined, hierarchical, and so on. It varies from “we have a culture of continuous improvement,” “pursuit of excellence,” to simply “it's like the Wild West.”

Years ago at another CLM Annual Global Conference, the keynote speaker was Joel Arthur Barker and he was promoting his book, Future Edge.4 My takeaway from his talk, which has stuck with me for many years, was that people live in paradigms. He defined a paradigm as “a set of rules (written or unwritten) that does two things: (1) it establishes or defines boundaries; and, (2) it tells you how to behave inside the boundaries in order to be successful.” This simple definition has helped me with assessing and understanding the culture of a company. Company culture establishes the rules of behavior inside the company. Culture is the company's paradigm.

The Smart Supply Network

What if everyone in your supply chain is connected in real time? What if every shipping unit is “labeled” with electronic AutoID (automatic identification) and RFID (radio frequency identification)? What if every transport container is GPS (global positioning system) enabled and can be monitored and tracked?

Every person in the network has the capability to share his or her local expert knowledge to manage and respond to change at any time and anywhere. As change occurs, perhaps a promotion or sales initiati...