![]()

Chapter 1

Overview of the Municipal Bond Market

INTRODUCTION

Municipal bonds, or municipal securities, represent a promise by state or local governmental units (called the issuers) or other qualified issuers to repay to lenders (investors) an amount of money borrowed, called principal, along with interest according to a fixed schedule. Municipal bonds generally are repaid, or mature, anywhere from 1 to 40 years from the date they are issued. At the end of 2010, there were $2.9 trillion in municipal bonds outstanding, representing the cumulative issuance of bonds over many years. These bonds have been used to finance a vast array of projects; a small sample includes:

- Elementary and secondary school buildings.

- Streets and roads.

- Government office buildings.

- Higher-education buildings, research laboratories, and dormitories.

- Transportation facilities, including bridges, highways, roads, airports, ports, and surface transit.

- Electric power-generating and -transmission facilities.

- Water tunnels and sewage treatment plants.

- Resource recovery plants.

- Hospitals, health-care and assisted living facilities, and nursing homes.

- Housing for low- and moderate-income families.

The municipal bond market is composed of thousands of dedicated professionals throughout the United States who have the diverse skills needed to raise money in the capital markets for state and local governments. Distinct roles are played by state and local government officials, public finance investment bankers, underwriters, salespeople, traders, analysts, lawyers, financial advisors, rating agencies, insurers, commercial bankers, investors, brokers, technology developers and vendors, the media, and regulators; yet all are working together toward the common goal of providing funds to state and local government units to build needed public projects and infrastructure.

Municipal securities are also commonly called tax-exempt bonds, because the interest paid to the investor is subject neither to federal income taxes nor (often) to state or local taxation. With regard to tax exemption, it must be noted that each household and organization's tax status is unique and different. Although this book delineates the general principles of municipal bonds, investors should consult with their own financial advisors when considering the purchase or sale of municipal securities.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 created Build America Bonds and other categories of municipal bonds where the interest is taxable to investors. The issuing municipalities received a grant from the federal government equal to 35 percent of the interest payments, which meant that the effective cost to the issuer was comparable to, or sometimes better than, the rate they would pay on a conventional tax-exempt municipal bond. The Build America Bonds program expired on December 31, 2010, and at the time of this writing had not been renewed.

In addition, a small market exists for taxable municipal bonds typically issued for purposes that are not eligible for either tax exemption under the U.S. tax code or a federal interest subsidy. Throughout this book, references to municipal bonds are to tax-exempt securities or Build America Bonds, except where it is expressly stated that they are taxable bonds that do not qualify for the federal interest subsidy.

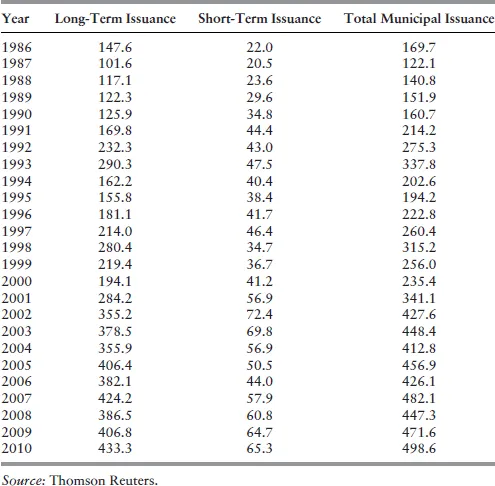

One statistic that is key to understanding the municipal bond market is the dollar volume of new bond issues that are sold each year. Fluctuations in volume can reflect national economic trends as well as events that are unique and specific to the municipal bond market. The causes and effects of volume changes in the municipal market will be examined in detail throughout this book, which also includes a general discussion of the overall level of interest rates. Table 1.1 tracks 25 years of new-issue volume.

Table 1.1 Total Long-Term and Short-Term Municipal Issuance 1986 to 2010 ($ billions)

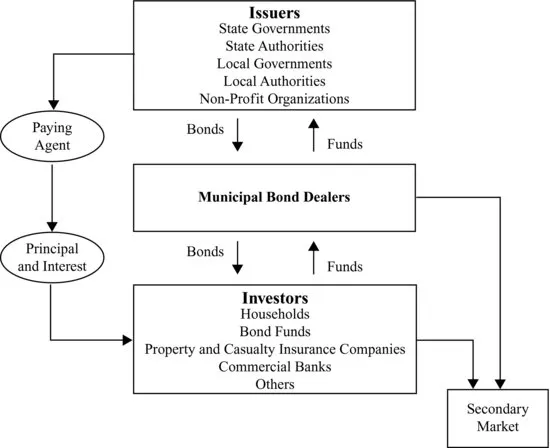

The municipal bond market consists of the primary market, which deals in the new securities of issuers, and the secondary market, where securities are bought, sold, and traded after they have been issued. Figure 1.1 presents the flow of funds through the primary market.

The process begins when an issuer sees a need for money to pay for capital improvements or to fill gaps in its cash flow. The issuer then takes a series of steps that lead to the primary market. There, the municipal bond dealer, usually a securities firm or a bank, purchases the issuer's bonds through a process called underwriting. The bonds are resold to institutional and individual investors, who pay the dealer directly for the debt they have purchased. The dealer uses these funds to reimburse itself for its capital that was used to purchase the bonds from the issuer. If an issue is underwritten and there are not enough buyers for all the bonds being issued, the underwriter assumes the risk of holding the bonds in inventory until they are eventually sold. Both principal and interest are paid to the investors by the issuer, usually through a bank acting as paying agent, on a fixed schedule.

The secondary market consists of the trading and other activity in securities after they have been sold as new issues. This market also supports the primary market by providing liquidity to investors who are more likely to buy a security if they know they can sell that security at a fair market price prior to its stated maturity. Most municipal bond dealers have trading departments that make secondary markets in outstanding bond issues.

THE ISSUERS

According to the 2007 U.S. Economic Census, there were more than 89,500 units of state and local governments. The Census categorizes governmental units as states, counties, municipalities, towns and townships, school districts, and special districts. Municipal bonds are issued by state and local governmental units, either directly under their own names or through a special authority. An authority is a separate state or local governmental issuer expressly created to issue bonds or to run an enterprise, or both. Authorities such as those for transportation or power can issue bonds on their own behalf. Other authorities can issue bonds for the benefit of other, qualified, nongovernmental parties, such as not-for-profit hospitals, private colleges, and certain private companies.

Municipal bonds are authorized and issued pursuant to express state and local laws, which impose restrictions on the size and financial structure of the debt. Moreover, each new issue usually requires the approval of the governing body of the issuer, sometimes through an ordinance or resolution. Bonds are generally sold to provide funds for capital improvement projects—for the bricks and mortar that make up the public infrastructure. With few exceptions, bonds are not sold to finance the normal, everyday operating expenses of government, such as employees’ salaries and benefits. States and local governmental units—such as counties, municipalities (which include cities), and school districts—issue bonds for roads, parks, courthouses, and schools. These securities are usually general obligation bonds (GOs) for which the full faith, credit, and taxing power of the issuer is pledged to and obliged to be used for the repayment of the bonds. Depending on the governmental issuer, approval by voter referendum is frequently required for the issuance of GOs. The public purpose projects funded by GOs provide benefits for the common good and so are repaid by taxes on everyone who is subject to taxes in that governmental unit. There are times when it is not feasible or possible to provide a general obligation pledge, so other forms of tax-backed or tax-supported bonds have been developed to provide a financing structure. Tax-backed bonds are discussed in greater depth throughout the book.

State and local governments also sell securities for which specific revenues, not governments’ full faith, credit, and taxing power, are the source of repayment. These obligations are known as revenue bonds. The issuer can be the government itself or a separate authority. Revenue bonds are issued for the construction of facilities and plants that provide electric power, water, wastewater treatment, and resource recovery and transportation, among others. Revenues and user fees that can be pledged to the bonds include electric rates and charges, water and sewage usage fees, waste disposal and tipping fees, and tolls and landing fees.

Table 1.2 shows the average issuance in each of eight broad categories of state and local governmental issuers in the 10-year period from 2000 through 2009 as a percentage of the total new-issue market by dollar volume. State authorities, including housing, economic development, transportation, and other state-level authorities, were the largest category of issuers, followed by similar bodies created at the local or regional level. Cities, towns, and villages were the largest government issuers, followed by states and counties or parishes.

Table 1.2 Issuers of Long-Term Municipal Bonds, 2000 to 2009

Note: Average annual issuance as a percent of dollar volume.

Source: Thomson Reuters.

| State authority | 31.8 |

| Local authority | 18.3 |

| District | 16.0 |

| City, town, or village | 13.3 |

| State governments | 10.3 |

| County/parish | 6.3 |

| College or university | 2.5 |

| Direct issuer | 1.1 |

| Total | 100.0 |

Table 1.3 Major Uses of Municipal Debt, 1989 and 2009

Source: Thomson Reuters.

| General purpose/public improvement | 24.5 | 31.4 |

| Education | 15.6 | 22.3 |

| Transportation | 8.8 | 12.0 |

| Health care | 12.5 | 11.2 |

| Water, sewer, and gas | 12.6 | 10.2 |

| Other | 8.2 | 4.9 |

| Public power | 6.7 | 3.9 |

| Housing | 9.2 | 2.5 |

| Pollution control | 1.9 | 1.5 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Although municipal bonds are issued for thousands of unique projects, they can be classified in a few broad categories, which may change over time. Table 1.3 lists the purposes for which bonds were issued in 1989 compared t...