Part I

Nailing Forensic Psychology: A Moving Target

In this part . . .

The work done by forensic psychologists covers an increasingly wide range of topics; everything from exploring how to detect deception and malingering all the way through to helping families who have juvenile delinquents in their midst. Other examples are helping witnesses to remember and assessing how dangerous a person really is. These professional contributions occur in many different institutions: law courts, prisons, special secure hospitals for people sent there by the courts, in the community at large and on rare occasions even as part of police investigations. They concern themselves with all sorts of criminals from arsonists to terrorists and crimes starting with every letter of the alphabet in between.

At the heart of what forensic psychologists do is an understanding of criminals, their actions and the causes of their behaviour. This links to many other people who are interested in criminals such as criminologists, lawyers and even doctors and geographers. The difference is that psychologists focus on the person rather than patterns of crime, with that person’s thoughts and emotions rather than physical or sociological processes. To get started, there is a lot of ground to clear about what forensic psychology is and the basis of what forensic psychologists do. In this part, I map out the fundamentals to get you ready for the more detailed stuff later.

Chapter 1

Discovering the Truth about Forensic Psychology

In This Chapter

Figuring out what forensic psychology is and isn’t

Seeing where forensic psychology happens

Understanding how forensic psychologists know what they know

Finding out who forensic psychologists work with

If you think that you know what forensic psychology is, this chapter may well have a few surprises in store. The abundance of police movies, TV series and crime novels give you a great picture of what forensic psychologists do – sometimes wrongly. Yes, police movies and TV series are truly criminal in content, but often only in terms of their inaccuracies and simplifications! Forensic psychology is an ambitious and diverse discipline and in this chapter I take a look at some specifics of the profession to sort out the reality from the fiction.

Whatever activity a forensic psychologist is involved in, he’s arriving at logical conclusions using systematic, scientific procedures. The forensic psychologist’s work is founded as much as possible on objective research, which isn’t always easy to do for reasons I discuss in this chapter.

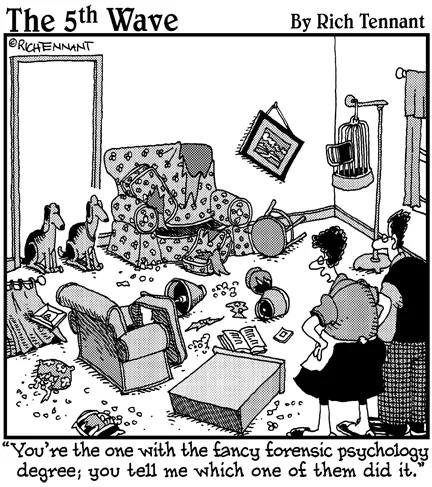

Grasping What Forensic Psychology Is Not

You know the typical crime movie plot, which goes something along the following lines: the detectives in the film are stumped (you’d have no plot if they found the criminal sitting crying at the crime scene). The serial killer has killed again (why are most killers in films serial killers?) and the pressure is on to find him (or more rarely, her). Enter the forensic psychologist, usually grudgingly, just when he’s having enough problems, with drink, his girlfriend, or both. He visits the crime scene and magically knows what the murderer was thinking, why he killed, and how the police can catch him. But the killer refuses to talk, and so the heroic forensic psychologist settles down for an intellectual battle of wits leading to the criminal revealing all. (Along the way of course the forensic psychologist loses custody of his darling daughter, his girlfriend walks out on him again, and he returns to the bottle.)

I’m no scriptwriter, but I’m sure the scene is familiar to you. Well, as this book and this chapter shows, the typical crime storyline has more to do with Conan Doyle’s fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, and all the well-known fictional sleuths following in his footsteps, than with the work of the present-day forensic psychologist.

Often, the best way of understanding the details of a professional activity is to clear the area around the profession and so establish what it’s not. This approach is particularly important for forensic psychology, which shares friendly, neighbourly relationships with many other areas and professions. You’d certainly be forgiven for thinking, for example, that forensic psychology is the same as criminology.

Journalists mistakenly often refer to me as a criminologist, even though I’m no expert on changes in the pattern of crime over the centuries or between different countries, and I know little about the effects of different forms of punishment on the prevalence of crimes or the effectiveness of different crime prevention strategies.

I know only a little about crime as a general area, but have spent my entire career as a forensic psychologist taking a lot of interest in criminals. And yet, as a forensic psychologist, I may criticise general considerations of how to cut crime or treat offenders, but journalists generally have little understanding about what I know about how criminals act and think.

Forensic psychologists don’t:

Study broad trends in criminality.

Examine how the legal system works.

Finding out that forensic psychology isn’t forensics

Forensic psychology isn’t forensics, which is the application of science in legal investigations, such as the chemistry of poisons, the physics of bullets, determining the time of death or how a person was killed. In other words, all the aspects of the Crime Scene Investigation featuring in so many TV crime series.

The examination of the scene of a crime and the exploration of the forensic evidence that can be drawn from the crime is sometimes useful to a forensic psychologist, for example in challenging an offender’s claim in therapy.

Although in some crime fiction the forensic scientist may offer up opinions about the mental state of the offender or similar speculations to keep the storyline moving, this activity is quite different to forensic psychology.

Distinguishing forensic psychology from psychiatry

Psychologists aren’t psychiatrists – doctors treating mental illness and related matters, which some legal systems call ‘diseases of the mind’. Psychiatrists are allowed to prescribe drugs and other forms of medical treatment and specialise in working with people who have problems in relating or their ability to deal effectively with others and the world around them.

To help their patients, psychiatrists may use talking therapies as well as medical interventions. Treatment can include the type of intensive psychotherapy initiated by Sigmund Freud, called psychoanalysis. When they’re not prescribing pills, electric shock therapy, or brain surgery and are treating their mentally ill patients by non-invasive means, psychiatrists are drawing on psychological research.

Although some overlap exists between forensic psychology and forensic psychiatry, most of the topics in this book – such as testimony, measuring aspects of personality and mental state, giving guidance on court procedures, and many aspects of the psychological treatment of offenders – are carried out by forensic psychologists. When psychiatrists are involved in assessment and treatment, I believe that they’re practising forensic psychology. They may not agree, however.

Recognising What Forensic Psychology Is

Psychologists start out studying general psychology, focusing on such things as memory, learning, personality, and social interaction. Psychology students examine which bits of the brain light up when different activities are engaged in and the biological and genetic basis of human experience. Therefore they do study some of the areas that medical students explore, but in far less detail.

After finishing general undergraduate training, psychologists can specialise in a number of different areas of psychology, including occupational, educational, health, or even environmental psychology. Psychologists do further training, if they want to get a professional post in one of these areas. (In Chapter 18, I list the stages in becoming a professional forensic psychologist.)

Psychologists working at providing assessment and therapy with mentally ill people are called clinical psychologists, and their activities overlap with those of psychiatrists. In times past there was quite a turf war going on between clinical psychologists and psychiatrists...