![]()

Chapter 1

Corrosion of Materials

Corrosion comes from Latin word “corrodere.” Plato talked about corrosion first in his lifetime (B.C. 427–347), defining rust as a component similar to soil separated from the metal. Almost 2000 years later, Georgius Agricola gave a similar definition of rust in his book entitled Mineralogy, stating that rust is a secretion of metal and can be protected via a coating of tar. The corrosion process is mentioned again in 1667 in a French-German translation, and in 1836 in another translation done by Sir Humphrey Davy from French to English, where cathodic protection of metallic iron in seawater is mentioned. Around the same time, Michael Faraday developed the formulas defining generation of an electrical current due to electrochemical reactions.

To one degree or another, most materials experience some type of interaction with a large number of diverse environments. Often, such interactions impair a material’s usefulness as a result of the deterioration of its mechanical properties, e.g., ductility, strength, other physical properties, and appearance. Deteriorative mechanisms are different for three material types, which are ceramics, polymers, and metals. Ceramic materials are relatively resistant to deterioration, which usually occurs at elevated temperatures or in extreme environments; that process is also frequently called “corrosion.” In the case of polymers, mechanisms and consequences differ from those for metals and ceramics, and the term “degradation” is most frequently used. Polymers may dissolve when exposed to liquid solvent, or they may absorb the solvent and swell. Additionally, electromagnetic radiation, e.g., primarily ultraviolet and heat, may cause alterations in their molecular structures. Finally, in metals, there is actual material loss, either by dissolution or corrosion, or by the formation of a film or nonmetallic scales by oxidation; this process is entitled “corrosion” as well.

1.1 Deterioration or Corrosion of Ceramic Materials

Ceramic materials, which are sort of intermediate compounds between metallic and nonmetallic elements, may be thought of as having already been corroded. Thus, they are exceedingly immune to corrosion by almost all environments, especially at room temperature, which is why they are frequently utilized. Glass is often used to contain liquids for this reason.

Corrosion of ceramic materials generally involves simple chemical dissolution, in contrast to the electrochemical processes found in metals. Refractory ceramics must not only withstand high temperatures and provide thermal insulation, but in many instances, must also resist high temperature attack by molten metals, salts, slags, and glasses. Some of the more useful new technology schemes for converting energy from one form to another require relatively high temperatures, corrosive atmospheres, and pressures above the ambient. Ceramic materials are much better suited to withstand most of these environments for reasonable time periods than are metals.

1.2 Degradation or Deterioration of Polymers

Polymeric materials deteriorate by noncorrosive processes. Upon exposure to liquids, they may experience degradation by swelling or dissolution. With swelling, solute molecules actually fit into the molecular structure. Scission, or the severance of molecular chain bonds, may be induced by radiation, chemical reactions, or heat. This results in a reduction of molecular weight and a deterioration of the physical and chemical properties of the polymer.

Polymeric materials also experience deterioration by means of environmental interactions. However, an undesirable interaction is specified as degradation, rather than corrosion, because the processes are basically dissimilar. Whereas most metallic corrosion reactions are electrochemical, by contrast, polymeric degradation is physiochemical; that is, it involves physical as well as chemical phenomena. Furthermore, a wide variety of reactions and adverse consequences are possible for polymer degradation. Covalent bond rupture, as a result of heat energy, chemical reactions, and radiation is also possible, ordinarily with an attendant reduction in mechanical integrity. It should also be mentioned that because of the chemical complexity of polymers, their degradation mechanisms are not well understood.

Polyethylene (PE), for instance, suffers an impairment of its mechanical properties by becoming brittle when exposed to high temperatures in an oxygen atmosphere. In another example, the utility of polyvinylchloride (PVC) may be limited because it is colored when exposed to high temperatures, even though such environments do not affect its mechanical characteristics.

1.3 Corrosion or Deterioration of Metals

Among the three types of materials that deteriorate, “corrosion” is usually referred to the destructive and unintentional attack of a metal, which is an electrochemical process and ordinarily begins at the surface. The corrosion of a metal or an alloy can be determined either by direct determination of change in weight in a given environment or via changes in physical, electrical, or electrochemical properties with time.

In nature, most metals are found in a chemically combined state known as an ore. All of the metals (except noble metals such as gold, platinum, and silver) exist in nature in the form of their oxides, hydroxides, carbonates, silicates, sulfides, sulfates, etc., which are thermodynamically more stable low-energy states. The metals are extracted from these ores after supplying a large amount of energy, obtaining pure metals in their elemental forms. Thermodynamically, as a result of this metallurgical process, metals attain higher energy levels, their entropies are reduced, and they become relatively more unstable, which is the driving force behind corrosion. It is a natural tendency to go back to their oxidized states of lower energies, to their combined states, by recombining with the elements present in the environment, resulting in a net decrease in free energy.

Since the main theme of the book is cathodic protection, which is a preventive measure against corrosion of metals, the remainder of the chapter will focus on the associated corrosion processes of widely used metals before going into details of cathodic protection. One shall have an idea about the corrosion process so that a more comprehensive understanding of cathodic protection process is possible.

Therefore, first, commonly used metals will be reviewed in terms of their corrosion tendencies, beginning with iron and steel, which are the most commonly used structural metals, and thus the most commonly protected ones with cathodic protection.

1.3.1 Iron, Steel and Stainless Steels

Iron and steel makes up 90% of all of the metals produced on earth, with most of it being low carbon steel. Low carbon steel is the most convenient metal to be used for machinery and equipment production, due to its mechanical properties and low cost. An example is the pressurized containers made of carbon steel that has 0.1% to 0.35% carbon. Carbon steel costs one-third as much as lead and zinc, one-sixth as much as aluminum and copper, and one-twentieth as much as nickel alloys. However, the biggest disadvantage of carbon steel is its low resistance to corrosion.

The most common mineral of iron in nature is hematite (Fe2O3), which is reacted with coke dust in high temperature ovens to obtain metallic iron. 1 ton of coke dust is used to produce 1 ton of iron. The naturally occurring reverse reaction, which is corrosion of iron back to its mineral form, also consists of similar products to hematite such as iron oxides and hydroxides. Energy released during the corrosion reaction is the driving factor for the reaction to be a spontaneous reaction; however, in some cases, even if the free Gibbs energy of the reaction is negative, due to a very slow reaction rate, corrosion can be considered as a negligible reaction, such as in the cases of passivation and formation of naturally protective oxide films.

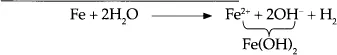

The anodic reactions during the corrosion of iron under different conditions are the same, and it is clearly the oxidation of iron producing Fe2+ cations and electrons. However, the cathodic reaction depends on the conditions to which iron is exposed. For example, when no or little oxygen is present, like the iron pipes buried in soil, reduction of H+ and water occurs, leading to the evolution of hydrogen gas and hydroxide ions. Since iron (II) hydroxide is less soluble, it is deposited on the metal surface and inhibits further oxidation of iron to some extent.

Thus, corrosion of iron in the absence of oxygen is slow. The product, iron (II) hydroxide, is further oxidized to magnetic iron oxide or magnetite that is Fe3O4, which is a mixed oxide of Fe2O3 and FeO. Therefore, an iron object buried in soil corrodes due to the formation of black magnetite on its surface.

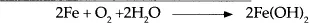

If oxygen and water are present, the cathodic reactions of corrosion are different. In this case, the corrosion occurs about 100 times faster than in the absence of oxygen. The reactions involved are:

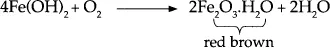

As oxygen is freely available, the product, iron (II) hydroxide, further reacts with oxygen to give red-brown iron (II) oxide:

The red brown rust is the most familiar form of rust, since it is commonly visible on iron objects, cars, and sometimes in tap water. The process of rusting is increased due to chlorides carried by winds from the sea, since chloride can diffuse into metal oxide coatings and form metal chlorides, which are more soluble than oxides or hydroxides. The metal chloride so formed leaches back to the surface, and thus opens a path for further attack of iron by oxygen and water.

Presence of pollutants i...