eBook - ePub

Scaffold Hopping in Medicinal Chemistry

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Scaffold Hopping in Medicinal Chemistry

About this book

This first systematic treatment of the concept and practice of scaffold hopping shows the tricks of the trade and provides invaluable guidance for the reader's own projects.

The first section serves as an introduction to the topic by describing the concept of scaffolds, their discovery, diversity and representation, and their importance for finding new chemical entities. The following part describes the most common tools and methods for scaffold hopping, whether topological, shape-based or structure-based. Methods such as CATS, Feature Trees, Feature Point Pharmacophores (FEPOPS), and SkelGen are discussed among many others. The final part contains three fully documented real-world examples of successful drug development projects by scaffold hopping that illustrate the benefits of the approach for medicinal chemistry.

While most of the case studies are taken from medicinal chemistry, chemical and structural biologists will also benefit greatly from the insights presented here.

The first section serves as an introduction to the topic by describing the concept of scaffolds, their discovery, diversity and representation, and their importance for finding new chemical entities. The following part describes the most common tools and methods for scaffold hopping, whether topological, shape-based or structure-based. Methods such as CATS, Feature Trees, Feature Point Pharmacophores (FEPOPS), and SkelGen are discussed among many others. The final part contains three fully documented real-world examples of successful drug development projects by scaffold hopping that illustrate the benefits of the approach for medicinal chemistry.

While most of the case studies are taken from medicinal chemistry, chemical and structural biologists will also benefit greatly from the insights presented here.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Scaffold Hopping in Medicinal Chemistry by Nathan Brown, Raimund Mannhold,Hugo Kubinyi,Gerd Folkers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pharmacology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Scaffolds: Identification, Representation Diversity, and Navigation

1

Identifying and Representing Scaffolds

1.1 Introduction

Drug discovery and design is an inherently multiobjective optimization process. Many different properties require optimization to develop a drug that satisfies the key objectives of safety and efficacy. Scaffolds and scaffold hopping, the subject of this book, are an attempt to identify appropriate molecular scaffolds to replace those that have already been identified [1,2]. Scaffold hopping has also been referred to as lead hopping, leapfrogging, chemotype switching, and scaffold searching in the literature [3–6]. Scaffold hopping is an approach to modulating important properties that may contravene what makes a successful drug: safety and efficacy. Therefore, due consideration of alternative scaffolds should be considered throughout a drug discovery program, but it is perhaps more easily explored earlier in the process. Scaffold hopping is a subset of bioisosteric replacement that focuses explicitly on identifying and replacing appropriate central cores that function similarly in some properties while optimizing other properties. While bioisosteric replacement is not considered to a significant degree in this book, a sister volume has recently been published [7], many of the approaches discussed in this book are also applicable to bioisosteric replacement.

Some properties that can be modulated by judicious replacement of scaffolds are binding affinity, lipophilicity, polarity, toxicity, and issues around intellectual property rights. Binding affinity can sometimes be improved by introducing a more rigid scaffold. This is due to the conformation being preorganized for favorable interactions. One example of this was shown recently in a stearoyl-CoA desaturase inhibitor [8]. An increase in lipophilicity can lead to an increase in cellular permeability. The replacement of a benzimidazole scaffold with the more lipophilic indole moiety was recently presented as a scaffold replacement in an inhibitor targeting N5SB polymerase for the treatment against the hepatitis C virus [9]. Conversely, replacing a more lipophilic core with the one that is more polar can improve the solubility of a compound. The same two scaffolds as before were used, but this time the objective was to improve solubililty, so the indole was replaced for the benzimidazole [10]. Sometimes, the central core of a lead molecule can have pathological conditions in toxicity that needs to be addressed to decrease the chances of attrition in drug development. One COX-2 inhibitor series consisted of a central scaffold of diarylimidazothiazole, which can be metabolized to thiophene S-oxide leading to toxic effects. However, this scaffold can be replaced with diarylthiazolotriazole to mitigate such concerns [11,12]. Finally, although not a property of the molecules under consideration per se, it is often important to move away from an identified scaffold that exhibits favorable properties due to the scaffold having already been patented. The definition of Markush structures will be discussed later in this chapter and more extensively in Chapter 2.

Given the different outcomes that lead to what can be called a scaffold hop, one can surmise that there must be different definitions of what constitutes a scaffold hop and indeed the definition of a scaffold itself. This chapter particularly focuses on identifying and representing scaffolds in drug discovery. Markush structures will be introduced as a representation of scaffolds for inclusion in patents to protect intellectual rights around a particular defined core, which will also be discussed in Chapter 2. Objective and invariant representations of scaffolds are essential for diversity analyses of scaffolds and understanding the scaffold coverage and diversity of our screening libraries. Some of the more popular objective and invariant scaffold identification methods will be introduced later in this chapter. The applications of these approaches will be discussed in more detail later in this book, with particular reference to the coverage of scaffolds in medicinal chemistry space.

1.2 History of Scaffold Representations

Probably the first description, which is still in common use today, is the Markush structure introduced by Eugene A. Markush from the Pharma-Chemical Corporation in a patent granted in 1924 [13]. Markush defined a generic structure in prose that allowed for his patent to cover an entire family of pyrazolone dye molecules:

I have discovered that the diazo compound of unsulphonated amidobenzol (aniline) or its homologues (such as toluidine, xylidine, etc.) in all their isomeric forms such as their ortho, meta and para compounds, or in their mixtures or halogen substitutes, may be coupled with halogen substituted pyrazolones (such as dichlor-sulpho-phenyl-carboxlic-acid pyrazolone) to produce dyes which are exceptionally fast to light, which will dye wool and silk from an acidulated bath.

More specifically, Markush's claims were as follows:

1. The process for the manufacture of dyes which comprises coupling with a halogen-substituted pyrazolone, a diazotized unsulphonated material selected from the group consisting of aniline, homologues of aniline and halogen substitution products of aniline.

2. The process for the manufacture of dyes which comprises coupling with a halogen-substituted pyrazolone, a diazotized unsulphonated material selected from the group consisting of aniline, homologues of aniline and halogen substitution products of aniline.

3. The process for the manufacture of dyes which comprises coupling dichlor-substituted pyrazolone, a diazotized unsulphonated material selected from the group consisting of aniline, homologues of aniline and halogen substitution products of aniline.

Interestingly, the careful reader will note that claims 1 and 2 in Markush's patent are exactly the same. It is not known why this would have been the case, but it may be speculated that it was a simple clerical error with Markush originally intending to make a small change in the second claim as can be seen in the third claim. Therefore, Markush's patent may not have been as extensive since it is possible one of his claims did not appear in the final patent.

Markush successfully defended his use of generic structure definitions at the US Supreme Court, defining a scaffold together with defined lists of substituents on that scaffold. Extending the chemistry space combinatorially from this simple schema can lead to many compounds being covered by a single patent. However, there remains a burden on the patent holders that although it may not be necessary to synthesize every exemplar from the enumerated set of compounds, each of the compounds must be synthetically feasible to someone skilled in the art. A patent may not be defendable if any of the compounds protected by a Markush claim cannot subsequently be synthesized.

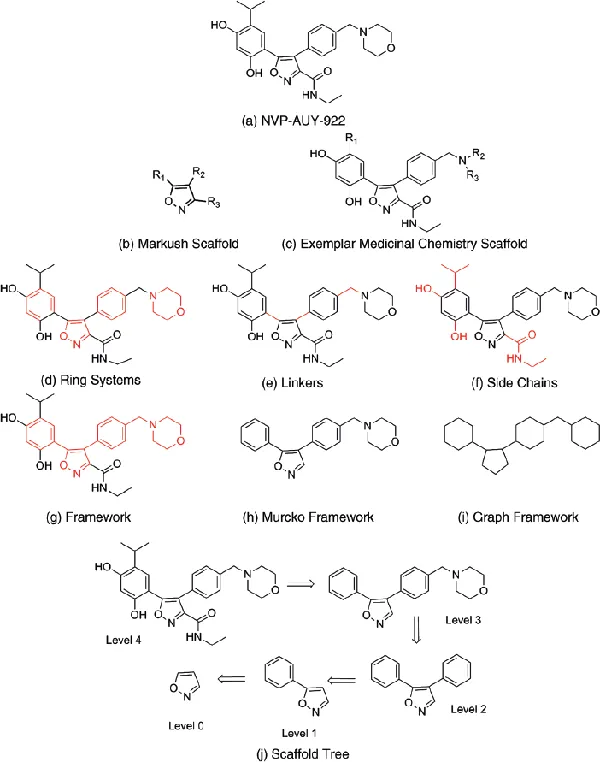

An example of a possible Markush structure for the HSP90 inhibitor, NVP-AUY922 (Figure 1.1a) is given in Figure 1.1b. However, an example of a medicinal chemist may determine as the molecular scaffold is given in Figure 1.1c [14,15].

Figure 1.1 The HSP90 inhibitor NVP-AUY922 depicted using different scaffold representations. (Reproduced from Ref. [20].)

The Markush claim discussed above is clearly a mechanism for extending the protection of a single patent application to a multitude of related and defined compounds. The earliest reference to what we would now call a molecular scaffold definition that this author could identify was in 1969, in an article published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, which provided the following definition [16]:

The ring system is highly rigid, and can act as a scaffold for placing functional groups in set geometric relationships to one another for systematic studies of transannular and multiple functional group effects on physical and chemical properties.

Clearly, this is a simple description of what constitutes a molecular scaffold and is readily understandable to a scientist active in medicinal chemistry and a specific example of a structural scaffold. However, its simple definition belies an inherent challenge in the identification of molecular scaffolds. Quite often, a medicinal chemist can identify what they would refer to as a molecular scaffold. This often involves identification of synthetic handles. The challenge here though is to understand how the scaffold has been determined, but this is a soft problem that is not capable of being reduced to an objective and invariant set of rules for scaffold identification. An expert medicinal chemist will bring to bear a wealth of knowledge from their particular research foci during their career and knowledge of synthetic routes: essentially, their intuition. Given a molecule, there are many ways of fragmenting that molecule that may render the key molecular scaffold of interest for the domain of applicability.

1.3 Functional versus Structural Molecular Scaffolds

Scaffolds can be divided roughly into two particular classes: functional and structural. A functional scaffold can be seen as a scaffold that contains the interacting elements with the target. Once defined, medicinal chemistry design strategies can concentrate on further improving potency while also optimizing selectivity and other properties, such as improving solubility. Conversely, a structural scaffold is one that literally provides the scaffolding of exit vectors in the appropriate geometries to allow key interacting moieties to be introduced to decorate the scaffold.

1.4 Objective and Invariant Scaffold Representations

It is important to be able define objective and invariant scaffold representations of molecules not only to permit rapid calculation of the scaffold representations but to also allow comparisons between the scaffolds of different molecules. Much research continues into objective and invariant scaffold representations, but here we summarize some of the methods that have seen significant utility. These scaffold representations use definitions of structural components of molecules: ring systems (Figure 1.1d), linkers (Figure 1.1e), side chains (Figure 1.1f), and the framework that is a connected set of ring systems and linkers (Figure 1.1g).

1.4.1 Molecular Frameworks

One of the first approaches to generating molecular scaffolds from individual molecules was the molecular framework (often referred to as Murcko frameworks) and graph framework representations [17]. Here, each molecule is treated independently; therefore, the method is objective and invariant.

The molecular framework is generated from an individual molecule by pruning all acyclic substructures that do not connect two cyclic systems (Figure 1.1h). Th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Methods and Principles in Medicinal Chemistry

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- A Personal Foreword

- Part One: Scaffolds: Identification, Representation Diversity, and Navigation

- Part Two: Scaffold-Hopping Methods

- Part Three: Case Studies

- Index