- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This tenth anniversary revised edition of the authoritative text on Christianity's first thousand years of history features a new preface, additional color images, and an updated bibliography. The essential general survey of medieval European Christendom, Brown's vivid prose charts the compelling and tumultuous rise of an institution that came to wield enormous religious and secular power.

- Clear and vivid history of Christianity's rise and its pivotal role in the making of Europe

- Written by the celebrated Princeton scholar who originated of the field of study known as 'late antiquity'

- Includes a fully updated bibliography and index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Rise of Western Christendom by Peter Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Empire and Aftermath

A.D. 200–500

1

“The Laws of Countries”: Prologue and Overview

One World, Two Empires

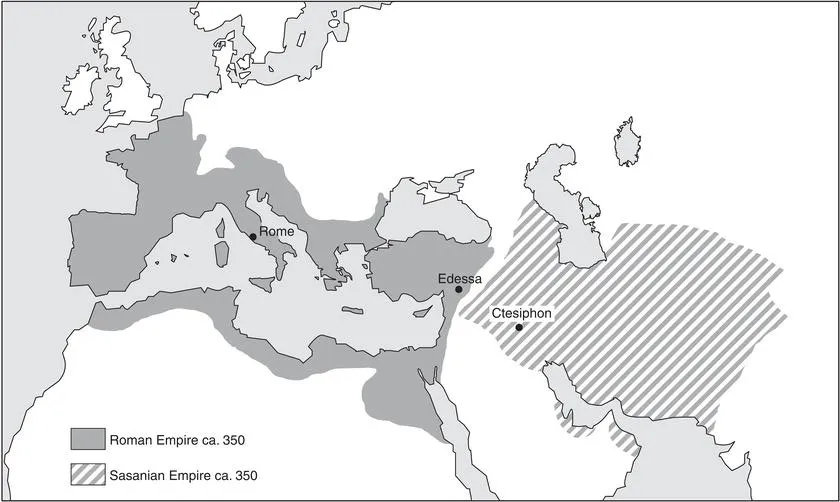

To ensure that we see the history of western Europe in its true perspective, we should begin our account in a city far away from modern Europe. Edessa (modern Urfa) now lies in the southeastern corner of Turkey, near the Syrian border. In the year A.D. 200, also, it was a frontier town, positioned between the Roman and the Persian empires. It lay at the center of a very ancient world, to which western Europe seemed peripheral and very distant.

Edessa was situated at the top of the Fertile Crescent, the band of settled land which stretched, in a great arch, to join Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean coast. It lay in a landscape already settled for millennia. Tels – the hill-like ruins of ancient cities dating back to the third millennium B.C. – dot the plain around it. Abraham was believed to have resided in Harran, a city a little to the south of Edessa, and to have passed through Edessa, as he made his way westward from Ur of the Chaldees in Mesopotamia, to seek his Promised Land on the Mediterranean side of the Fertile Crescent.

To the west of Edessa, an easy journey of 15 days led to Antioch and to the eastern Mediterranean, the sea which formed the heart of the Roman empire. To the southeast, another journey of 15 days led to the heart of Mesopotamia, where the Tigris and the Euphrates came closest. This was a zone of intensive cultivation which had supported the capitals of many empires. Here Ctesiphon was founded, in around A.D. 240. Its ruins now lie a little to the south of modern Baghdad. Ctesiphon was the Mesopotamian capital of the Sasanian dynasty, a family from southwest Iran, who took over control of the Persian empire in A.D. 224. The Sasanian empire joined the rich lands around Ctesiphon to the Iranian plateau. Beyond the Iranian plateau lay the trading cities of Central Asia and, yet further to the east, the chain of oases that led the traveller, over the perilous distances of the Silk Route, to the legendary empire of China.

Map 1 The world ca.350: the Roman and Sasanian empires

CHRISTIANITY AND EMPIRE ca. 200–ca. 450

| Bardaisan 154–ca.224 224 Rise of Sasanian Empire Mani 216–277 | |

| 257 Edict against Christians | |

| Cyprian, bishop of Carthage 248–258 | |

| 284–305 Diocletian 303 Great Persecution | |

| 306–337 Constantine 312 Battle of Milvian Bridge 324 Foundation of Constantinople 325 Council of Nicaea | |

| Anthony 250–356 Arius 250–336 Athanasius of Alexandria 296–373 | |

| 337–361 Constantius II | |

| Martin of Tours 335–397 Ambrose of Milan 339–397 Melania the Elder 342–411 Paulinus of Nola 355–431 | |

| 378 Battle of Adrianople 379–395 Theodosius I 390 Massacre of Thessalonica | |

| Augustine of Hippo 354–430 writes Confessions 397/400 | |

| 406 Barbarian invasion of Gaul 410 Sack of Rome | |

| writes City of God 413+ Pelagian Controversy 413+ | |

| 408–450 Theodosius II as Eastern emperor | |

| 438 issues Theodosian Code | |

| 434–453 Empire of Attila the Hun |

In the early third century, Edessa was the capital of the independent kingdom of Osrhoene. Bardaisan (154–222) was a nobleman and learned figure at the royal court. He represented the complex strands of a culture which drew on both the East and the West. Greek visitors admired his skills as a Parthian (Persian) archer. But, as a philosopher, he was entirely Greek. When a faithful disciple wrote a treatise summarizing Bardaisan’s views on the relation between determinism and free will, he began it with a Platonic dialogue between two Edessene friends, Shemashgram and Awida. Yet the dialogue was not written in Greek but in Syriac, a language which was soon to become a major literary language in the Christian churches of the Middle East.

Bardaisan, furthermore, was a Christian, at a time when Christianity was still a forbidden religion within the Roman empire. He interpreted his faith in broad, geographical terms. The point that he wished to make was that, wherever they lived, human beings were free to choose their own way of life. They were not determined by the influence of the stars. Each region had its own customs, and Christians showed the extent of the freedom of the will by ignoring even these customs, and by seeking, rather, to live under “the laws of the Messiah” – of Christ. “In whatever place they find themselves, the local laws cannot force them to give up the law of the Messiah.”

Bardaisan’s treatise was appropriately named The Book of the Laws of Countries. It scanned the entire Eurasian landmass from China to the north Atlantic. It described the local customs of each society – the caste-dominated society of northern India, the splendidly caparisoned horses and fluttering silk robes of the Kushan lords of Bokhara and Samarkand, the Zoroastrians of the Iranian plateau, the Arabs of Petra and of the deserts of Mesopotamia. It even turned to the remote west, to observe the impenitent polyandry of the Britons. Naturally, it included the Romans, whom no power of the stars had ever been able to stop “from always conquering new territories.”1

Any book on the role of Christianity in the formation of western Europe must begin with the sweep of Bardaisan’s vision. This book studies the emergence of one form of Christendom only among the many divergent Christianities which came to stretch along the immense arc delineated in Bardaisan’s treatise. We should always remember that the “Making of Europe” involved a set of events which took place on the far, northwestern tip of that arc. Throughout the entire period covered by this book, as we shall see, Christians were active over the entire stretch of “places and climates” which made up the ancient world of the Mediterranean and western Asia. Christianity was far from being a “Western” religion. It had originated in Palestine and, in the period between A.D. 200 and 600, it became a major religion of Asia. By the year 700 Christian communities were scattered throughout the known world, from Ireland to Central Asia. Archaeologists have discovered fragments of Christian texts which speak of basic Christian activities pursued in the same manner from the Atlantic to the edge of China. Both in County Antrim, in Northern Ireland, and in Panjikent, east of Samarkand, fragmentary copybooks from around A.D. 700 – wax on wood for Ireland, broken potsherds for Central Asia – contain lines copied from the Psalms of David. In both milieux, something very similar was happening. Schoolboys, whose native languages were Irish in Antrim and Soghdian in Panjikent, tried to make their own, by this laborious method, the Latin and the Syriac versions, respectively, of what had become a truly international, sacred text – the “Holy Scriptures” of the Christians.2

Less innocent actions also betray the workings of a common Christian mentality. As we shall see, the combination of missionary zeal with a sense of cultural superiority, backed by the use of force, became a striking feature of early medieval Christian Europe. But it was not unique to that region. In around 723, Saint Boniface felled the sacred oak at Geismar and wrote back to England for yet more splendid copies of the Bible to display to his potential converts. They should be “written in letters of gold … that a reverence for the Holy Scriptures may be impressed on the carnal minds of the heathen.”3

At much the same time, Christian Nestorian missionaries from Mesopotamia were waging their own war on the great sacred trees of the mountain slopes that rose above the Caspian. They laid low with their axes “the chief of the forest,” the great sacred tree which had been worshipped by pagans. Like Boniface, the Nestorian bishop Mar Shubhhal-Isho’ knew how to impress the heathen: he

made his entrance there with exceeding splendor, for barbarian nations need to see a little worldly pomp and show to attract them to make them draw nigh willingly to Christianity.4

Even further to the east, in an inscription set up in around A.D. 820 at Karabalghasun, on the High Orkhon river, the Uighur ruler of an empire formed between China and Inner Mongolia, recorded how his predecessor, Bogu Qaghan, had introduced new teachers into his kingdom in A.D. 762. These were Manichaeans. As bearers of a missionary faith of Christian origin, the Manichaean missionaries in Inner Asia shared with the Nestorians a similar brusque attitude toward the conversion of the heathen. The message of the inscription is as clear and as sharp as that which Charlemagne had adopted, between 772 and 785, when he burned the great temple of the gods at Irminsul and outlawed paganism in Saxony. Bogu Qaghan said:

We regret that you were without knowledge, and that you called the evil spirits “gods.” The former carved and painted images of the gods you should burn, and you should cast far from you all prayers to spirits and to demons.5

It goes without saying that these events had no direct or immediate repercussions upon each other. Yet they do bear a distinct family resemblance. They show traces of a common Christian idiom, based upon shared traditions. They remind us of the sheer scale of the backdrop against which the emergence of a specifically western Christendom took place.

The principal concern of this book, however, will be to characterize what, eventually, would make the Christendom of western Europe different from that of its many, contemporary variants. In order to do this, let us look briefly at another aspect of Bardaisan’s geographical panorama. The vivid gallery of cultures known to him appeared to stretch from China to Britain along a very narrow band. Bardaisan was oppressed by the immensity of the unruly, underdeveloped world of the “barbarians,” which stretched to the north and south of the civilized world. Grim stretches of sparsely populated land flanked the vivid societies he described.

In the whole regions of the Saracens, in Upper Libya, among the Mauritanians … in Outer Germany, in Upper Sarmatia … in all the countries North of Pontus [the Black Sea], the Caucasus … and in the lands across the Oxus … no one sees sculptors or painters or perfumers or money changers or poets.

The all-important amenities of settled, urban living were not to be found “along the outskirts of the whole world.”6

It was a sobering vision, shared by most of Bardaisan’s Greek and Roman contemporaries. It was eminently appropriate in a man bounded by two great empires – the Roman and the Persian. These two great states controlled, between them, most of the settled land of Europe and western Asia. Both were committed to sustaining the belief, among their subjects, that their costly military endeavors were directed toward defending the civilized world against barbarism. In the words of a late sixth-century diplomatic manifesto, sent by the Persian King of Kings to the Byzantine emperor:

God effected that the whole world should be illuminated from the beginning by two eyes [the Romans and the Persians]. For by these greatest powers the disobedient and bellicose tribes are trampled down and man’s course is continually regulated and guided.7

It is against the backdrop of a vast world patrolled by two great empires, which stretched with little break from Afghanistan to Britain, that we begin our story of the rise and establishment of Christianity in western Europe.

Who are the Barbarians? Nomads and Farmers

The empires which controlled the settled lands invariably presented themselves as defending “civilization” against the “barbarians.” Yet what each empire meant by “barbarian,” and the relations which each established with the “barbarians” on its own frontiers, varied markedly from region to region. Western Europe became what it now is because the relations which the Roman empire established with the “barbarians” along its northern frontiers proved to be quite unusual. Compared with the relations between the ancient empires of the Middle East and the nomads of the Arabian desert and of the steppes of Central Asia, the “barbarians” of the Roman West were hardly “barbarians” at all. For they were farmers, not nomads.

We must always remember that “barbarian” meant many things to Bardaisan and his contemporaries. It could mean nothing more than a “foreigner,” a vaguely troubling, even fascinating, person from a different culture and language-group. By this criterion, Persians were “barbarians.” To Greeks and to an easterner such as Bardaisan, even Romans were “barbarians.” But, for Bardaisan as for most Greeks and Romans, “barbarian” in the strong sense of the word meant, in effect, “nomad.” Nomads were seen as human groups placed at the very bottom of the scale of civilized life. The desert and the sown were held to stand in a state of immemorial and unresolved antipathy, with the desert always threatening, whenever possible, to dominate and destroy the sown.8

In North Africa and the Middle East, of course, there was little truth in this melodramatic stereotype. For millennia, pastoralists and peasants had collaborated, in a humdrum and profitable symbiosis. Nomads were treated as a despised but useful underclass. It was assumed that these wanderers, though often irritating, could never constitute a permanent threat to the great empires of the settled world, much less replace them. Because of a contempt for the desert nomad which reached back, in the Middle East, to Sumerian times, the Arab conquests of the seventh century (the stunning work of former nomads) and the consequent foundation of the Islamic empire took contemporaries largely by surprise. Wholesale invasion and conquest from the hot desert of Arabia had not been expected.

The nomads who had always been feared (and with reason) were, rather, those of the cold north, from the steppelands which stretched from the puszta of Hungary, across the southern Ukraine, to Central and Inner Asia. Here conditions favored the intermittent rise of aggressive and well-organized nomadic empires.9 Herds of fast, sturdy horses bred rapidly and with little cost on the thin grass of the northern steppes. These overabundant creatures, when mounted for war, gave to the nomads the terrifying appearance of a nation in arms, endowed with uncanny mobility. One such confederacy of Huns from Central Asia penetrated the Caucasus into the valleys of Armenia, in the middle of the fourth century:

no one could number the vastness of the cavalry contingents [so] every man was ordered to carry a stone so as to throw it down … so as to form a mound … a fearful sign [left] for the morrow to understand past events. And wherever they passed, they left such markers at every crossroad along their way.10

The sight of such cairns was likely to stick in the memory. Unimpressed by the desert nomads of Arabia and the Sahara, the rulers of the civilized world scanned the nomadic world of the northern steppes with anxious attention.

Yet, terrifying though the nomadic empires of the steppes might be, they were an intermittent phenomenon. Effective nomadism...

Table of contents

- Cover

- The Making of Europe

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- List of Illustrations

- Preface to the Tenth Anniversary Revised Edition

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Introduction

- Part I: Empire and Aftermath A.D. 200–500

- Part II: Divergent Legacies A.D. 500–600

- Part III: The End of Ancient Christianity A.D. 600–750

- Part IV: New Christendoms A.D. 750–1000

- Notes

- Coordinated Chronological Tables

- Bibliography

- Plates

- Index