![]()

EXECUTIVE FORUM

The Discipline of Virtual Teams

BY JON R. KATZENBACH AND DOUGLAS K. SMITH

“I have discovered another impact of the virtual team,” exclaimed a project coordinator of the “Gaia Project” (a disguised name). “It keeps me up all hours of the day and night!” In just over a year, the roughly three dozen people associated with the Gaia Project collaborated to set a time-to-market record for designing a new subsystem demanded by main players in the evolving global automotive markets. The effort spanned more than a dozen time zones, half a dozen languages, and four continents. Most, but not all, came from the same company, and there were a score or more specific functional, managerial, or other specialties. Different cultures, countries, and languages; different companies, work sites, and skill-sets; plus different processes and hierarchical levels—all collaborated within the integrating construct of a commonly shared goal.

Sound familiar? Well, if not, welcome to the world of virtual teaming—a phenomenon sweeping the global workplace as fast as the tentacles of the Internet are encircling your office, home, car, and cell phone. Like it or not, you are interconnected, and that means you can work with any person from any enterprise in any place at any time on any challenge. The list of opportunities fueling the demand for such collaboration includes partnering, joint ventures, strategic alliances, outsourcing, customer and supplier relationship management, plus hundreds of less exotic corporate interactions. Whether your organization has 10,000 people or just 10, you will face the challenge of working virtually with people down the hall, around the corner, as well as across continents and oceans. As a result, your work group will need to develop new and different rules of engagement—including when and how to interrupt one another’s dinners!

Virtual teaming was little more than a novelty phrase in the early 1990s when The Wisdom of Teams was first published. Our purpose in writing that book was to challenge conventional wisdom that teaming was merely about engendering a feeling of togetherness, teamwork, and empowerment. Instead, Wisdom argues that team performance requires adherence to a simple set of disciplined behaviors that we call “team basics.” When applied to appropriate performance challenges, that discipline produces results that are clearly superior to what small groups can obtain operating in a traditional hierarchy under a command-and-control discipline. Millions of people have since acted on the key messages in Wisdom:

- A compelling and commonly held performance challenge is what creates teams, not the desire to be a team.

- Teaming demands a six-part discipline whereby a small number of people with complementary skills commit to hold themselves mutually accountable to a common purpose, a set of common goals, and a commonly agreed-upon way of working together.

- Unlike hierarchy, team leadership is more about building mutual accountability and performance focus than making decisions and delegating tasks.

- If your small group can achieve its performance goals through the sum of individual assignments and achievements, then you should not use a team approach. Traditional hierarchy and a single-leader discipline is a more efficient way to meet your goals. But if your group’s performance objective requires people to deliver work and results jointly, with multiple leadership inputs, then you are well advised to use the team discipline.

Our latest book, The Discipline of Teams, argues that virtual work groups that seek team performance must master two different disciplines: “single leader” and “team.” Paradoxically, each discipline becomes both easier and harder to apply because of group work technology, also called groupware. While groupware includes some old friends like phone and fax, it is increasingly characterized by new acquaintances, for example, threaded discussions (the ability to order verbal interchanges by topic, person, date, and time) and “simulchats” (a melding of teleconferencing and computer chat room technology). But proficiency in groupware is not the critical factor in virtual team performance. In fact, it is clearly secondary to the basics of team discipline. If the people in your group get this wrong, they will e-mail themselves straight into a nonperformance booby trap: relying on technology to elevate performance when the real problem is undisciplined behavior.

Two Disciplines, Not One

Team performance, be it virtual or not, is primarily about discipline—leader, peer, and self-imposed. So start by recognizing that your group must master two disciplines, not just one. Each demands more than applying the mere fundamentals of effective group behavior that most of us have been trained in for years now. For example, what really mattered to the Gaia Project was not technological proficiency. It was how the members differentiated between two critical situations: individual tasks and goals that members could achieve under clear single-leader direction, and critical collective work that demanded real-time collaboration, multiple leadership, and the disciplined behavior of a real team. These options have little to do with technology, although both can certainly be enabled by groupware.

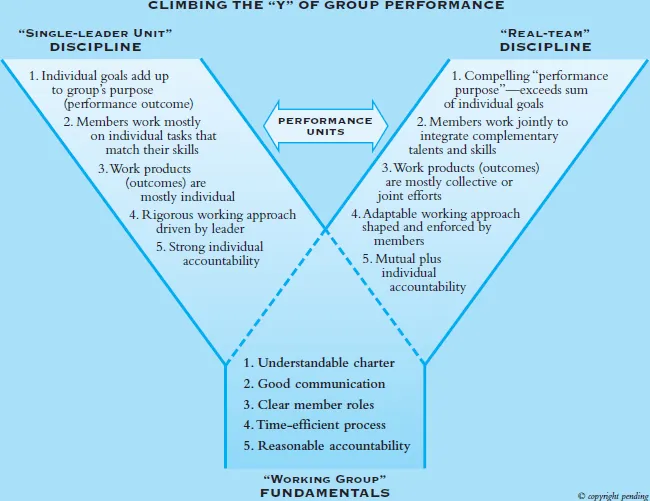

The “Y” chart shown in the figure was developed by Katzenbach Partners LLC to clarify the differences between effective groups and true performance units.

The base of the “Y” describes the elements of effective group work, not performance units. The left branch defines the discipline required to elevate effective groups to single-leader performance units (characterized by speed and efficiency, leadership clarity, and individual accountability). The right branch defines the discipline required to elevate effective groups to real-team performance units (characterized by collective work products, shifting leadership roles, and mutual accountability). The choice of branch depends on the performance situation, as the Gaia Project soon discovered.

The difference between single-leader and team disciplines is straightforward: tasks and goals that are best accomplished by individuals working within a single leader’s direction versus tasks and goals that require close collaboration among two or more people working together in real time with access to multiple leaders. Even the best groupware technology cannot make up for the failure to manage according to this distinction. As this was colorfully put to us in an interview, “Some ‘atomic tasks’ of collaboration cannot be broken down further!” Try to divide such atoms and your project can blow up like a nuclear bomb. Work them collectively and, like the Gaia Project, you can exceed all expectations.

As happens so often in team efforts, the easy part was farming out separate tasks to the individuals with the skills required to complete them. These are the kinds of assignments that move a group up the left-hand branch of the “Y” in the figure, and when people apply the principles of the single-leader discipline, good results follow.

At the same time, as one project member pointed out, “The designs of modules created separately were very good by themselves, but the interfaces were not compatible.” In other words, the different components, no matter how well done, would not integrate themselves. Engineers and designers had to do that by working together along the right-hand branch of the “Y”—where only some of their collective efforts could be enabled by groupware. Like many groups, the Gaia Project discovered the hard way that together does not mean apart, even with the assistance of groupware.

People as far flung as California and India could and did use phone calls, e-mail, videoconferencing, and a variety of collaboration tools customized to work across their networks. They did not succeed, however, until they chose to hold a small number of engineers, designers, and assemblers mutually accountable for integrating the components—a key element in the right-hand branch of the Y. The most critical integrating behaviors required co-located interactions. The members simply needed to work together at the same time in the same room!

Why? Because a small number of people who must deliver a collective piece of work are more likely to succeed when they can be physically together, to see and interpret well beyond what electronic communication can convey. Co-location permits people to respond in real time to ideas, body language, tone, and other nonverbal communications. They can ask each other spontaneous questions. They can challenge ideas on the spot without offending one another.

They can informally explore each other’s hypotheses and test preliminary reactions. Best of all, they can avoid fatal assumptions.

While groupware helps people share words, thoughts, and ideas, it lacks many of the informal essentials of communication and collaboration that only face-to-face interactions can provide. The obstacles experienced by the Gaia Project were typical:

- “We didn’t understand what the software group in Europe were saying in their e-mail. Either their tone or their thoughts. There were actions we thought they should take. But, often, they threw the ball into our court.”

- “Sometimes we received e-mail from people we didn’t even know were on the team.”

- “Phones are good. But sometimes it is hard to understand accents. And with the nine-hour time difference, you have to think very carefully about the questions you are going to ask.”

- “You have to make assumptions frequently. Yet even a slight misunderstanding can cause the project to suffer by many days.”

Once the Gaia Project members realized they needed the team discipline to accomplish collective tasks and goals, they were able to eliminate troublesome barriers and get back on track. One contributor, who was temporarily moved from India to California, said, “There were problems on technical issues slowing the project down—things not possible to solve even by talking on the phone every day. Once I was transferred to San Jose, the project sped up considerably.”

Using the Technology Well

Jackie Moore is the U.K.-based human resource director for American Express Technology (AET). As leader of a virtual-team effort, she quickly learned that although groupware technology can help in getting a small number of people to work virtually, it cannot “do it for you.” In April 1998, when the human resources and development team supporting AET reorganized, shared purpose rather than location determined team membership. Jackie wound up with a team of direct reports scattered throughout the world who had to provide their clients with on-site representation and local support. Their efforts were integrated around a common vision: helping technology experts of American Express partner with business leaders to grow the overall company.

They created a team to meet a clear performance goal: to deliver valuable technical support and client service in a world of virtual work.

Groupware has helped them share information, build rich databases, interact across time zones, and store and access complex work products. They also had to communicate frequently with one another and their clients. The core of their challenge, however, was neither defined nor resolved by the technology. They still had to create trust across different cultures, apply multiple leadership approaches, meld the complementary skills of different members, integrate individual and collective work products, and enforce individual and mutual accountability. These are the basics of team performance, and they demand disciplined behavior. In short, applying the right disciplines, although facilitated by technology, was not superseded by technology.

Performance units like AET still have to inject strong, direct leadersh...