The world once seemed simple, manufacturers made things and services companies did things for us. Today, more and more manufacturers are competing through a portfolio of integrated products and services. This is a services-led competitive strategy, and the process through which it is achieved is commonly referred to as servitization. Celebrated icons of such strategies in action include Rolls-Royce, Xerox and Alstom, who all offer some form of extended maintenance, repair and overhaul contracts where revenue generation is directly linked to asset availability, reliability and performance.

Servitization is, however, much more than simply adding services to existing products within a few large multinational companies. It’s potentially about viewing the manufacturer as a service provider. A service provider that sets out to improve the processes of their customers through a business model rather than product-based innovation. The manufacturer then exploits its design and production-based competences to give widespread improvements in efficiency and effectiveness to the customer.

Manufacturers have, however, traditionally focused their efforts on product innovation and cost reduction. Companies such as Porsche and Ferrari have been celebrated for bringing new and exciting designs into the market, while companies such as Toyota have been held in awe for their work with Lean production systems. These successes can foster a perception that the only way for manufacturing to underpin competitiveness is through new materials and technologies, faster and more reliable automation, machining with more precision, waste reduction programmes, smoother flow of parts, employee engagement, and closer coupling within the supply chain.

Services offer a third way to compete. This is not an ‘instead of’ or ‘easy option’ for companies that are struggling to succeed. Indeed, delivering some types of advanced services can require a set of technologies and practices that are every bit as demanding as those in production. Neither does this require the manufacturer to abandon its technology strengths; instead these can be developed to help ensure long term competitiveness. Consequently, there is a growing realization that such services hold high-value potential.

Ironically, manufacturers competing on the basis of service provision is not a new phenomenon. In the 1800s, International Harvester used services to help establish their new reaping equipment among farmers in the American Midwest. Similarly, origins of power-by-the-hour lie partially in the practices of Bristol Siddeley in the 1960s. Perhaps what is new is our willingness as a business community to recognize that ‘manufacturing’ is not just about product innovation, process technologies and production. We are abandoning a production-centric paradigm to embrace a broader view of manufacturing.

A few manufacturers have been following this route for some time. To illustrate, over the past 20 years there has been an intense debate in the West about the rights and wrongs of outsourcing and off-shoring to China and India. Many in manufacturing have held out hope that the tide would in some way turn. While some production activities have been relinquished, key manufacturers have been quietly moving forward in their supply chains to take over service activities carried out by their customers. Services have been key to their survival, and as a consequence our language and perceptions are now changing.

Conventional manufacturers can struggle, however, to appreciate the value of services. Managers often seek such a simple explanation of servitization that they fail to appreciate how such a strategy is likely to be of significant benefit. This is often the case with organizational rather than technological innovations. In the early 1980s it was difficult to imagine that ‘Just-in-Time’ would endure, and yet today it’s hard to identify a single manufacturing company that has not been touched by Lean techniques in one way or another.

Servitization is a similar paradigm shift. Success requires managers to hold a different mindset or worldview to their colleagues in production. The challenge is equivalent to persuading a manager skilled in Lean techniques to appreciate the value in craft production. Yet some niche producers excel through their exploitation of such systems (e.g. Holland & Holland in their manufacture of high-value sporting guns). So, how can the value of services be thoroughly introduced and explained to those who are more familiar with a production-centric view of the world? This is the challenge we have taken up in this book.

Our purpose is to guide conventional manufacturers through the concept of servitization. To achieve this we have tackled the topic in four progressive steps. First, we set about illustrating the conditions in the business world that are causing services to become increasingly relevant for manufacturers. Second, we give illustrations and examples of a services-led competitive strategy, and pay particular attention to those ‘advanced’ services that are widely associated with servitization. Third, we paint a picture of what it takes to compete on the basis of advanced services, and delve into the technologies and practices that leading manufacturers have adopted. Finally, we summarize the conditions that favour the take-up of servitization within a manufacturer.

Collectively, these four parts outline a potential organizational transformation. Our goal has been to explain servitization in such a way that mainstream manufactures will, through following this book, be better equipped to fully understand the relevance of this concept to their broader operations.

1.1 Terminology and Scope

The word ‘services’ conjures up a variety of interpretations. The later sections of this book will clarify many of the key terms in detail. Here we give a few critical descriptions that provide a foundation for the following chapter and indicate the general scope of the book – as the following headings indicate.

This book deals with manufacturers

All forms of organizations deliver services. In everyday life we come across many organizations that seem entirely engaged with delivering services alone, such as banks, insurance brokers, local government, schools, and hospitals. Sometimes these companies use product nomenclature (for example, an insurance product or a mortgage product) and have many similarities with conventional production systems. However, we consider these as ‘pure-service providers’ and do not study them further.

This book is written for those businesses that engage in product manufacture. We adopt a broad definition of manufacturing and take it to mean that the company has some authority over the design and production of the products with which it deals. We recognize that this terminology does not rest comfortably with some companies who are advanced in servitization. Xerox, for instance, would describe themselves as a services-led technology company; others might choose to be known as a solutions business or services provider. However, we use the term manufacturing simply to anchor the content of this book, and draw a distinction for these organizations from pure-service providers.

Our intention is to impact all forms of manufacturing. Unfortunately many of the leading examples of servitization are businesses which are large, and produce expensive and technically complex products. Yet such companies are not our exclusive target; many lessons in this book are generally applicable.

Manufacturers servitizing through advanced services

The word service can be used in different ways. For example, service can refer to how well an action is performed (‘that was good service’). Alternatively it can be used to refer to an activity; (e.g., helpdesk, maintenance, training or spare parts provision). Our focus is on the latter use of the word service; activities that a manufacturer can perform to complement the products it produces. All manufacturers offer services to some extent, but some establish market differentiation through these, and so can be thought of as following services-led competitive strategies.

Servitization is a term given to a transformation. It is about manufacturers increasingly offering services integrated with their products. Of these, some manufacturers choose to servitize by offering an extensive portfolio of relatively conventional services. Others move almost entirely into pure services, largely independent of their products, and provide offerings such as general consulting. Others still move to deliver advanced services.

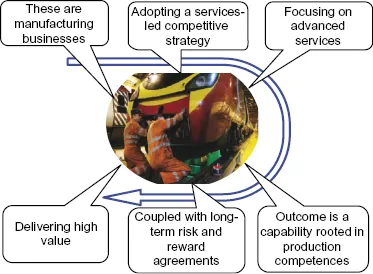

Advanced services are a special case in servitization. Sometimes known as outcome, capability or availability contracts, here the manufacturer delivers services (coupled with incentivized contracting mechanisms) that are critical to their customers’ core business processes. The contracts associated with this type of offering frequently extend over many years, with the manufacturer adopting greater risk by taking responsibility for the performance of its products, and being rewarded through ongoing and more profitable revenue streams. ‘Power-by-the-hour’, as offered by Rolls-Royce, is an iconic example of such a service.

These advanced services can hold high value for manufacturers. They can help strengthen relationships, lock out competitors, grow revenues and profits. As a consequence these are the services on which this book is concerned. Our particular focus is on manufacturers taking bold moves into providing advanced services as summarized in Figure 1.1.

Advanced services are delivered through product–service systems (PSS)

Servitization involves both the innovation of the service offering and also the innovation of the manufacturer’s internal capabilities in operations. This delivery system is just as important as the offering itself. Just as Henry Ford changed the world, not just through the design of his automobile (the Model T), but also his system of mass production that enabled high volumes of products to be produced at a very low price.

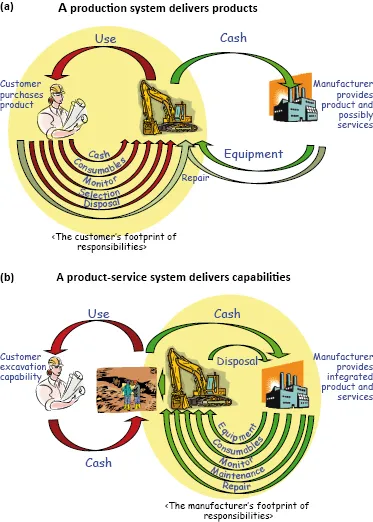

Production systems deliver products; advanced services are delivered by product–service systems. These systems are based on very different interactions with the customer. Figure 1.2 illustrates how each of these systems may appear, based around the example of the provision of excavator equipment.

In the production world the manufacturer produces the equipment (the excavator in Figure 1.2). When this is sold the manufacturer is rewarded financially. Although the customer may only want to use the equipment, to do so it has to first raise finance for its purchase, and then provide the necessary consumables (e.g. fuel, lubrication, tyres). They also have to monitor the equipment’s performance and, should a problem begin to arise, the customer invariably performs some diagnostics before then arranging maintenance and repair. These services may well be carried out by either the customer themselves, the original manufacturer, or an independent repair shop on the customer’s behalf. Eventually the equipment wears and needs replacing. Once again the customer becomes engaged, both in new equipment selection, and the disposal of the old. This is a transactional-based ‘production and consumption’ business model; the responsibilities of ownership lie with the customer, and the revenue stream for the manufacturer is largely based around product sale and spare parts.

Within a PSS, the manufacturer still produces the equipment. However, ownership and the associated responsibilities are not necessarily transferred to the customer; rather the manufacturer sets out to provide a ‘capability’ (an excavation capability in the case of Figure 1.2). Understanding the customer’s requirement, the manufacturer rather than the customer then takes responsibility for equipment selection, consumables, monitoring of performance, and carrying out servicing and disposal. In return the manufacturer receives payment as the customer uses the capability that the equipment provides. This is a ‘value in use’ business model; the responsibilities for equipment performance lie with the manufacturer, who receives revenue as the equipment is used by the customer.

Neither production systems nor product–service systems operate in isolation. Both are supported by an ecosystem of suppliers and partners; but the roles of these differ from one system to another. In particular, the financial partner is a critical enabler that is often overlooked. Try asking how a manufacturer such as Rolls-Royce affords to provide gas turbines typically costing $10,000,000 on a power-by-the-hour contract? How can they afford to ‘own’ the gas turbine on their balance sheet? In this instance partners such as International Leasing and Financing Company (ILFC) can finance the purchase of the turbine and then lease it to the customer (user). This fee then forms part of the customer’s monthly payments on the power-by-the-hour contract. We will explore the role of suppliers later in the book, and pay particular attention to how they enable this financial model.

Product-service systems significantly impact the operations of the manufacturer

This book focuses on the broad operations of the servitized manufacturer. Just as many authors have given their attention to understanding Lean practices and technologies that support production, our goal has been to understand the system that has to be created to deliver advanced services e...