Responsible Innovation

Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Responsible Innovation

Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society

About this book

Science and innovation have the power to transform our lives and the world we live in - for better or worse – in ways that often transcend borders and generations: from the innovation of complex financial products that played such an important role in the recent financial crisis to current proposals to intentionally engineer our Earth's climate. The promise of science and innovation brings with it ethical dilemmas and impacts which are often uncertain and unpredictable: it is often only once these have emerged that we feel able to control them. How do we undertake science and innovation responsibly under such conditions, towards not only socially acceptable, but socially desirable goals and in a way that is democratic, equitable and sustainable? Responsible innovation challenges us all to think about our responsibilities for the future, as scientists, innovators and citizens, and to act upon these.

This book begins with a description of the current landscape of innovation and in subsequent chapters offers perspectives on the emerging concept of responsible innovation and its historical foundations, including key elements of a responsible innovation approach and examples of practical implementation.

Written in a constructive and accessible way, Responsible Innovation includes chapters on:

- Innovation and its management in the 21st century

- A vision and framework for responsible innovation

- Concepts of future-oriented responsibility as an underpinning philosophy

- Values – sensitive design

- Key themes of anticipation, reflection, deliberation and responsiveness

- Multi – level governance and regulation

- Perspectives on responsible innovation in finance, ICT, geoengineering and nanotechnology

Essentially multidisciplinary in nature, this landmark text combines research from the fields of science and technology studies, philosophy, innovation governance, business studies and beyond to address the question, "How do we ensure the responsible emergence of science and innovation in society?"

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Innovation in the Twenty-First Century

1.1 Introduction

- Where can we innovate?

- How can we innovate?

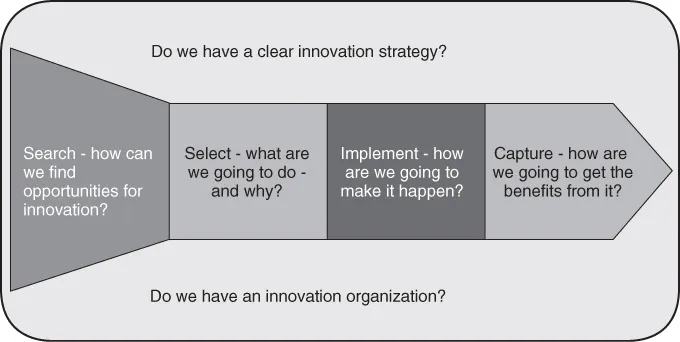

1.2 How Can We Innovate?—Innovation as a Process

1.3 Where Could We Innovate?—Innovation Strategy

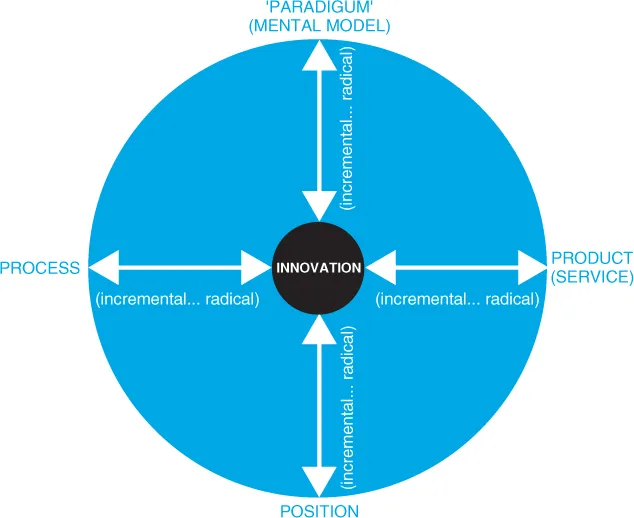

- “product innovation”—changes in the things (products/services) which an organization offers;

- “process innovation”—changes in the ways in which products and services are created and delivered;

- “position innovation”—changes in the context in which the products/services are introduced;

- “paradigm innovation”—changes in the underlying mental models which frame what the organization does.

| Innovation type | Incremental—do what we do but better | Radical—do something different |

| Product—what we offer the world | Windows 7® and Windows 8® replacing Vista® and XP®—essentially improving on an existing software idea | New to the world software—for example, the first speech recognition program |

| New versions of established car models—for example, the VW Golf essentially improving on established car design | Toyota Prius—bringing a new concept—hybrid engines. Tesla—high performance electric car. | |

| Improved performance incandescent light bulbs | LED-based lighting, using completely different and more energy efficient principles | |

| CDs replacing vinyl records—essentially improving on the storage technology | Spotify® and other music streaming services—changing the pattern from owning your own collection to renting a vast library of music | |

| Process—how we create and deliver that offering | Improved fixed line telephone services | Skype® and similar systems |

| Extended range of stock broking services | On-line share trading | |

| Improved auction house operations | eBay® | |

| Improved factory operations efficiency through upgraded equipment | Toyota Production System® and other “lean” approaches | |

| Improved range of banking services delivered at branch banks | Online banking and now mobile banking in Kenya, Philippines—using phones as an alternative to banking systems | |

| Improved retailing logistics | On line shopping | |

| Position—where we target that offering and the story we tell about it | Häagen-Daz® changing the target market for ice cream, from children to consenting adults | Addressing underserved markets—for example, the Tata Nano aimed at the emerging but relatively poor Indian market with cars priced around $2000 |

| Airlines segmenting service offering for different passenger groups—Virgin Upper Class, BA Premium Economy, and so on | Low cost airlines opening up air travel to those previously unable to afford it—create new markets and also disrupt existing ones | |

| Dell® and others segmenting and customizing computer configuration for individual users | Variations on the “One laptop per child” project—for example, Indian government $20 computer for schools | |

| On line support for traditional higher education courses | University of Phoenix and others, building large education b... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Foreword: Why Responsible Innovation?

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- Chapter 1: Innovation in the Twenty-First Century

- Chapter 2: A Framework for Responsible Innovation

- Chapter 3: A Vision of Responsible Research and Innovation

- Chapter 4: Value Sensitive Design and Responsible Innovation

- Chapter 5: Responsible Innovation—Opening Up Dialogue and Debate

- Chapter 6: “Daddy, Can I Have a Puddle Gator?”: Creativity, Anticipation, and Responsible Innovation

- Chapter 7: What Is “Responsible” about Responsible Innovation? Understanding the Ethical Issues

- Chapter 8: Adaptive Governance for Responsible Innovation

- Chapter 9: Responsible Innovation: Multi-Level Dynamics and Soft Intervention Practices

- Chapter 10: Responsible Innovation in Finance: Directions and Implications

- Chapter 11: Responsible Research and Innovation in Information and Communication Technology: Identifying and Engaging with the Ethical Implications of ICTs

- Chapter 12: Deliberation and Responsible Innovation: a Geoengineering Case Study

- Chapter 13: Visions, Hype, and Expectations: a Place for Responsibility

- Building Capacity for Responsible Innovation

- Name Index

- Subject Index