![]()

Chapter 1

Fundamental Logic and the Definition of Engineering Tasks

What there is to learn: For many important engineering tasks computers should provide choices, not answers. The type of engineering task will determine important aspects of computer support. The ‘open-world’ nature of engineering is a difficult challenge.

The success of computer software in engineering rarely depends upon the performance of the hardware and the system-support software. Computer applications have to match engineering needs. Although the principal objective of this book is to introduce fundamental concepts of computing that are relevant to engineering tasks, it is essential to introduce first the fundamental concepts of engineering that are relevant to computing. This is the objective of this first chapter, and key concepts are described in the following sections.

1.1 Three Types of Inference

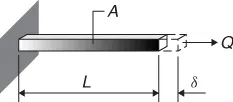

From the perspective of fundamental logic, engineering reasoning is categorized into the following three types of inference: deduction, abduction and induction. The best way to understand inference types is through an example. Consider a bar of length L and area A that is fixed at one end and loaded at the other with a load Q (Figure 1.1).

From fundamental solid mechanics and assuming elastic behaviour, when a load Q is applied to a prismatic bar having a cross-sectional area A, this bar deforms axially (elongates) by an amount δ = QL/AE where E is the Young's modulus of the material. Thus, for a given bar, we have the following items of information:

- two facts: Q and δ

- one causal rule: if Q then δ (a causal rule has the form, if cause then effect)

The difference between deduction, abduction and induction originates from what is given and what is inferred. Deduction begins with one fact Q and the causal rule. With these two items as given information, we infer that a deformation δ occurs. Abduction begins with the effect δ and the causal rule. Starting with these two items, we infer that a load Q is present. Induction begins with the two facts, Q and δ, and then infers the causal rule. Table 1.1 summarizes the important elements of these three types of inference.

Table 1.1 Three types of inference

| Deduction | Cause and rule | Effect |

| Abduction | Effect and rule | Cause |

| Induction | Cause and effect | Rule |

Logically, deduction is the only legal inference type in an open world. The use of abduction and induction requires a closed-world hypothesis. A closed world hypothesis involves the assumption that all facts and all rules are known for a given task. Such hypotheses are typically found at the beginning of mathematical proofs using statements such as ‘for all x …’ and ‘y is an element of …’.

For illustration, refer to the example of the loaded bar. We can state with some confidence that if there is a load Q and when the causal rule, if Q then δ, is known, we can infer that a deformation δ is expected (deduction). However, when we know the rule and only that a deformation δ is observed, we cannot necessarily say in an open world that this deformation was caused by a load Q (abduction). For example, the deformation may have been caused by an increase in temperature. Similarly, just because we observe that there is a load Q and a deformation δ, we cannot necessarily formulate the rule, if Q then δ (induction). Other facts and contextual information may justify the formulation of another rule. Abduction and induction become valid inferences for the example on hand only when we make the closed-world hypothesis that the only relevant items of information are the two facts and one rule.

Scientists and mathematicians frequently restrict themselves to closed worlds in order to identify in a formal manner kernel ideas related to particular phenomena. Also, the closed-world idea is not limited to research. Job definitions in factories, offices and many other places often only require decision-making based on closed, well-defined worlds. However, engineers (as well as other professionals such as doctors and lawyers) are not allowed to operate only in closed worlds. Society expects engineers to identify creative solutions in open worlds. For example, engineers consider social, economic and political aspects of most of their key tasks before reaching decisions. Such aspects are difficult to define formally. Moreover, attempts to specify them explicitly, even partially, are hindered by environments where conditions change frequently.

Therefore, engineers must proceed carefully when they perform abductive and inductive tasks. Since a closed-world hypothesis is not possible for most of these tasks, any supporting software needs to account for this. For example, engineering software that supports abductive tasks has to allow for frequent user interaction in order to accommodate open-world information. Also, providing good choices rather than single answers is more attractive to engineers. Differences in ‘world hypotheses’ provide the basic justification for variations between requirements of traditional computer software, such as those applied to book-keeping, and those applied to certain tasks in engineering. The next section will expand on this theme by providing a classification of engineering tasks according to their type of inference.

1.2 Engineering Tasks

Important engineering tasks are simulation, diagnosis, synthesis and interpretation of information. All of these tasks transform one type of information to another through inference. Some more terminology is needed. In this discussion the word structure refers to information that is commonly represented in drawings, such as dimensions, location, topography and other spatial information, as well as properties of materials and environmental influences such as temperature, humidity and salinity of the air. This category also includes the magnitude, direction and position of all loading that is expected to be applied to the object. The word behaviour is used to include parameters that describe how the structure reacts, such as deformations, stresses, buckling, shrinkage, creep and corrosion.

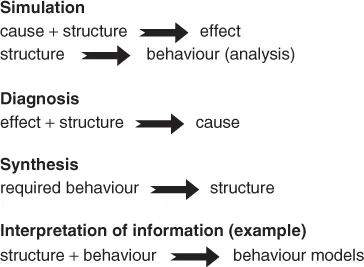

In simulation, causes are applied to particular structures in order to observe effects (or more precisely, behaviour). For example, a factory process is simulated to observe output and other aspects, such as sensitivity to breakdown of a machine. Analysis is a special case of simulation. Analysis is performed when behavioural parameters are required for a given physical configuration in a particular environment (the word structure is used loosely to define this information). For example, bridges are analysed for various loading (such as wind, truck and earthquake) in order to determine behaviour that is expressed in terms of stresses and deflections. These transformations are summarized in Figure 1.2.

Diagnosis can be thought of as the reverse of simulation. For this task, observed effects are considered with the physical configuration and the environment to infer causes. For example, maintenance engineers observe the vibrations of motors in order to identify the most likely causes. Similarly, from an information viewpoint, synthesis is the reverse of analysis, where target behaviour is used to infer a physical configuration within an environment. For example, engineers design building structures to resist many types of loading in such a way that stresses and deflections do not exceed certain values.

Interpretation of information includes a wide range of engineering activities. For example, interpretation of information refers to tasks that infer knowledge from activities such as load tests, commissioning procedures and laboratory experiments. Test results in the form of values of behavioural parameters are combined with known structure to infer models of behaviour. The form of the model may already be known; in such cases, testing is used for model calibration. For example, engineers test aircraft components in laboratories to improve knowledge of strength against fatigue cracking. These results are often used to improve models that predict behaviour of other components. Although such models are usually expressed in terms of formulae, they are transformable into causal rules, as in the example in Figure 1.1.

Each arrow in Figure 1.2 refers to an inference process where the left-hand side is the input, and the right-hand side is the output. Reviewing the definitions for deduction, abduction and induction that are given in Section 1.1, a classification of engineering tasks in terms of inference types becomes possible. Since deduction begins with known causes and causal rules to infer effects, analysis and simulation are examples of deduction. Abduction begins with known effects and causal rules to infer causes; therefore, diagnosis and synthesis are abductive inferences. Interpretation of information begins with know...