![]()

1

State of the Art – Nanomechanics

Amrita Saritha, Sant Kumar Malhotra, Sabu Thomas, Kuruvilla Joseph, Koichi Goda, and Meyyarappallil Sadasivan Sreekala

1.1 Introduction

Nanomechanics, a branch of nanoscience, focuses on the fundamental mechanical properties of physical systems at the nanometer scale. It has emerged on the crossroads of classical mechanics, solid-state physics, statistical mechanics, materials science, and quantum chemistry. Moreover, it provides a scientific foundation for nanotechnology. Often, it is looked upon as a branch of nanotechnology, that is, an applied area with a focus on the mechanical properties of engineered nanostructures and nanosystems that include nanoparticles, nanopowders, nanowires, nanorods, nanoribbons, nanotubes, including carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs), nanoshells, nanomembranes, nanocoatings, nanocomposites, and so on.

Nanotechnology can be broadly defined as “The creation, processing, characterization, and utilization of materials, devices, and systems with dimensions on the order of 0.1–100 nm, exhibiting novel and significantly enhanced physical, chemical, and biological properties, functions, phenomena, and processes due to their nanoscale size” [1]. Nanobiotechnology, nanosystems, nanoelectronics, and nanostructured materials, especially nanocomposites, are of current interest in nanotechnology. Polymer nanocomposites have gained attention as a means of improving polymer properties and extending their utility by using molecular or nanoscale reinforcements rather than conventional particulate fillers. The transition from microparticles to nanoparticles yields dramatic changes in physical properties.

Recently, the advances in synthesis techniques and the ability to characterize materials on atomic scale have led to a growing interest in nanosized materials. The invention of nylon 6/clay nanocomposites by the Toyota Research Group of Japan heralded a new chapter in the field of polymer composites. Polymer nanocomposites combine these two concepts, that is, composites and nanosized materials. Polymer nanocomposites are materials containing inorganic components that have dimensions in nanometers. In this chapter, the discussion is restricted to polymer nanocomposites made by dispersing two-dimensional layered nanoclays as well as nanoparticles into polymer matrices. In contrast to the traditional fillers, nanofillers are found to be effective even at as low as 5 wt% loading. Nanosized clays have dramatically higher surface area compared to their macrosized counterparts such as china clay or talc. This allows them to interact effectively with the polymer matrix even at lower concentrations. As a result, polymer–nanoclay composites show significantly higher modulus, thermal stability, and barrier properties without much increase in the specific gravity and sometimes retaining the optical clarity to a great extent. As a result, the composites made by mixing layered nanoclays in polymer matrices are attracting increasing attention commercially. Thus, the understanding of the links between the microstructure, the flow properties of the melt, and the solid-state properties is critical for the successful development of polymer–nanoclay composite products.

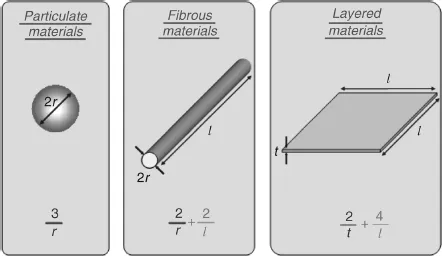

Nevertheless, these promising materials exhibit behavior different from conventional composite materials with microscale structure due to the small size of the structural unit and high surface area/volume ratio. Nanoscale science and technology research is progressing with the use of a combination of atomic scale characterization and detailed modeling [2]. In the early 1990s, Toyota Central Research Laboratories in Japan reported work on a nylon 6 nanocomposite [3], for which a very small amount of nanofiller loading resulted in a pronounced improvement in thermal and mechanical properties. Common particle geometries and their respective surface area/volume ratios are shown in Figure 1.1. For the fiber and the layered material, the surface area/volume ratio is dominated, especially for nanomaterials, by the first term in the equation. The second term (2/l and 4/l) has a very small influence (and is often omitted) compared to the first term. Therefore, logically, a change in particle diameter, layer thickness, or fibrous material diameter from the micrometer to nanometer range will affect the surface area/volume ratio by three orders of magnitude [4]. Typical nanomaterials currently under investigation include nanoparticles, nanotubes, nanofibers, fullerenes, and nanowires. In general, these materials are classified by their geometries; broadly, the three classes are particle, layered, and fibrous materials [4, 5]. Carbon black, silica nanoparticles, and polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes (POSS) can be classified as nanoparticle reinforcing agents while nanofibers and carbon nanotubes are examples of fibrous materials [5]. When the filler has a nanometer thickness and a high aspect ratio (30–1000) plate-like structure, it is classified as a layered nanomaterial (such as an organosilicate) [6]. The change of length scales from meters (finished woven composite parts), micrometers (fiber diameter), and submicrometers (fiber/matrix interphase) to nanometers (nanotube diameter) presents tremendous opportunities for innovative approaches in the processing, characterization, and analysis/modeling of this new generation of composite materials. As scientists and engineers seek to make practical materials and devices from nanostructures, a thorough understanding of the material behavior across length scales from the atomistic to macroscopic levels is required. Knowledge of how the nanoscale structure influences the bulk properties will enable design of the nanostructure to create multifunctional composites.

Wang et al. synthesized poly(styrene–maleic anhydride) (PSMA)/TiO2 nanocomposites via the hydrolysis and condensation reactions of multicomponent sol since the PSMA has functional groups that can anchor TiO2 and prevent it from aggregating [7]. Polystyrene or polycarbonate rutile nanocomposites have been synthesized by Nussbaumer et al. [8]. Singh et al. [9] studied the variation in fracture toughness of polyester resin due to the addition of aluminum particles of 20, 3.5, and 100 nm diameter. Results indicate an initial enhancement in fracture toughness followed by decrease at higher particle volume fraction. This phenomenon is attributed to the agglomeration of nanoparticles at higher particle volume content. Lopez et al. [10] examined the elastic modulus and strength of vinyl ester composites after the addition of 1, 2, and 3 wt% of alumina particles of 40 nm, 1 μm, and 3 μm size. For all particle sizes, the composite modulus increases monotonically with particle weight fraction. However, the strengths of composites are all below the strength of neat resin due to nonuniform particle size distribution and particle aggregation. The mechanical behavior of alumina-reinforced poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) composites was studied by Ash et al. [11].

1.2 Nanoplatelet-Reinforced Composites

In the case of layered silicates, the filler is present in the form of sheets one to a few nanometer thick and hundreds to thousands nanometer long. In general, the organically modified silicate nanolayers are referred to as “nanoclays” or “organosilicates” [12]. It is important to know that the physical mixture of a polymer and layered silicate may not form nanocomposites [13]. Pristine-layered silicates usually contain hydrated Na+ or K+ ions [13]. To render layered silicates miscible with other polymer matrices, it is required to convert the normally hydrophilic silicate surface into an organophilic one, which can be carried out by ion-exchange reactions with cationic surfactants [13]. Sodium montmorillonite (Na-MMT, Nax(Al2−xMgx)(Si4O10)(OH)2·mH2O)-type layered silicate clays are available as micron-sized tactoids, which consist of several hundred individual plate-like structures with dimensions of 1 μm × 1 μm × 1 nm. These are held together by electrostatic forces (the gap in between two adjacent particles is 0.3 nm). The MMT particles, which are not separated, are often referred to as tactoids. The most difficult task is to break down the tactoids to the scale of individual particles in the dispersion process to form true nanocomposites, which has been a critical issue in current research [14,15–24]. Natural flake graphite (NFG) is also composed of layered nanosheets [25], where carbon atoms positioned on the NFG layer are tightened by covalent bonds, while those positioned in adjacent planes are bound by much weaker van der Waals forces. The weak interplanar forces allow for certain atoms, molecules, and ions to intercalate into the interplanar spaces of the graphite. The interplanar spacing is thus increased [25]. As it does not bear any net charge, intercalation of graphite cannot be carried out by ion-exchange reactions in the galleries like layered silicates [25]. The original graphite flakes with a thickness of 0.4–60 mm may expand up to 2–20 000 mm in length [26]. These sheets/layers get separated down to 1 nm thickness, forming high aspect ratio (200–1500) and high modulus (~1 TPa) graphite nanosheets. Furthermore, when dispersed in the matrix, the nanosheet exposes an enormous interface surface area (2630 m2/g) and plays a key role in the improvement of both the physical and mechanical properties of the resultant nanocomposite [27]. The various preparative techniques for this type of nanocomposites are discussed below.

1.3 Exfoliation–Adsorption

This technique is based on a solvent system in which the polymer or prepolymer is soluble and the silicate layers are swellable. The layered silicates, owing to the weak forces that stack the layers together, can be easily dispersed in an adequate solvent such as water, acetone, chloroform, or toluene. When the polymer and the layered silicate are mixed, the polymer chains intercalate and displace the solvent within the interlayer of the silicate. The solvent is evaporated and the intercalated structure remains. For the overall process, in which polymer is exchanged with the previously intercalated solvent in the gallery, a negative variation in Gibbs free energy is required. The driving force for polymer intercalation into layered silicate from solution is the entropy gained by desorption of solvent molecules, which compensates for the decreased entropy of the intercalated chains. This method is good for the intercalation of polymers with little or no polarity into layered structures and facilitates production of thin films with polymer-oriented clay intercalated layers. The major disadvantage of this technique is the nonavailability of compatible polymer–clay systems. Moreover, this method involves the copious use of organic solvents, which is environmentally unfriendly and economically prohibitive. Biomedical poly(urethane–urea) (PUU)/MMT (MMT modified with dimethyl ditallow ammonium cation) nanocomposites were prepared by adding OMLS (organically modified layered silicate) suspended in toluene dropwise to the solution of PUU in N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAC). The mixture was then stirred overnight at room temperature, the solution was degassed, and the films were cast on round glass Petri dishes. The films were air dried for 24 h, and subsequently dried under vacuum at 50 °C for 24 h. Wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) analysis indicated the formation of intercalated nanocomposites [28]. The effects of heat and pressure on microstructures of isobutylene–isoprene rubber/clay nanocomposites prepared by solution intercalation (S-IIRCNs) were investigated [29]. A comparison of the WAXD patterns of untreated S-IIRCN and nanocomposites prepared by melt intercalation (M-IIRCN) reveals that the basal spacing of the intercalated structures in untreated M...