![]()

1

CLASSICAL STRAIN IMPROVEMENT

Nathan Crook and Hal S. Alper

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Improving complex phenotypes, which are typically multigenic in nature, has been a long-standing goal of the food and biotechnology industry well before the advent of recombinant DNA technology and the genomics revolution. For thousands of years, humans have (whether intentionally or not) placed selective pressure on plants, animals, and microorganisms, resulting in improvements to desired phenotypes. Clear evidence of these efforts can be seen from the dramatic morphological changes to food crops since domestication (1). These improvements have been predominantly achieved through a “classical” approach to strain engineering, whereby phenotypic improvements are made by screening and mutagenesis of strains that use methods naive of genome sequences or the resulting genetic changes. This approach is well suited for strain optimization in industrial microbiology, which commonly exploits complex phenotypes in organisms with poorly defined or monitored genetics. As a recognition of importance, Arnold Demain and Julian Davies begin their Handbook of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology with “Almost all industrial microbiology processes require the initial isolation of cultures from nature, followed by small-scale cultivations and optimization, before large-scale production can become a reality” (2). The classical approach is concerned with the central steps in this process—between isolation and large-scale production. Hence, the methods and techniques utilized in this approach amount to “unit operations,” that is, standard procedures that can be generically applied to any desired strain of interest.

A variety of approaches are used to force genetic (and hence phenotypic) diversity including naturally occurring genetic variation and genetic drift, mutagenesis, mating/sporulation, and/or selective pressures. These methods have garnered large successes across a wide range of host organisms owing mostly to the absence of required sophisticated genomic information or genetic tools (3). Thus, the classical approach can be applied to both model organisms (such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and newly isolated or adapted industrial strains. As a result, the classical approach has seen wide adoption in industrial fermentations due to its proven track record in alcohol and pharmaceutical production. Finally, strains developed in this manner are currently accorded non-genetically modified organism (GMO) status, removing significant barriers to their acceptance by both regulatory agencies and consumers. This chapter will highlight several of the approaches and successes that exemplify the classical approach for improving complex phenotypes of industrial cells as well as indicate its limitations and potential interfaces with emerging technology.

1.1 THE APPROACH DEFINED

The classical approach is characterized by the introduction of random mutations (either forced or natural) to a population of cells followed by screening and/or selection to isolate improved variants. The defining quality of classical strain engineering (as opposed to other evolutionary engineering methods) is genome-wide mutagenesis. This approach utilizes techniques that introduce variation across all regions of the genome, in contrast to other techniques that specifically target the mutations to single genes (or subsequences thereof). To date, this approach has been successful in improving complex phenotypes because of the global nature of classical methodologies (see Box 1.1 in this chapter and case study in Chapter 6). Complex phenotypes such as tolerance to environmental stress, altered morphology, and improved flocculation characteristics are often influenced by the interactions between multiple (often uncharacterized) genes. In contrast, without significant prior understanding, variants generated through mutagenesis of specific genomic subsections are unlikely to gain proper coverage of the genotype. Indeed, as will be discussed later, this approach has continuously yielded improved variants for a wide variety of complex biotechnological applications. The theory and techniques for the two major steps of classical strain improvement (CSI) (mutagenesis and screening) are the focus of this chapter, including practical recommendations for their implementation as well as brief discussion of examples of each method’s industrial application.

BOX 1.1: APPLICATION OF CSI IN SAKE FERMENTATION

The Japanese-brewed sake is produced from rice mash using Aspergillus oryzae to saccharify the rice and strains of sake yeast (genus Saccharomyces cerevisiae) to ferment the sugars to ethanol. The ideal process imposes a number of complex traits on the sake yeast, including high fermentation capacity over the 20- to 25-day process at low temperatures (typically 10°C), high ethanol tolerance (ethanol levels can approach 15–20%), minimal foaming, resistance to contaminating microbes, and the ability to create the correct proportion of flavor components including higher alcohols and esters (82). Many of these traits have been approached using methods of the classical approach including mutagenesis, selection, and cell mating. Specifically, UV and chemical mutagenesis have dominated as a means of retaining GRAS status for this yeast. Moreover, difficulty in sporulation has limited genetic dissection and a more rational approach until recently (83). Natural selection and isolation from hundreds of years of fermentation has resulted in the series of commonly used strains named the Kyokai series, with Kyokai no. 7 and Kyokai no. 9 as the main fermentation strains used industrially. Due to the superior brewing capacity of Kyokai no. 7, many attempts have been made to improve this strain through the classical approach as well as dissect the underlying genetic changes. Recently, it has been demonstrated that the breeding and selection process of this strain resulted in heterozygosity of many alleles responsible for ethanol production and aromatic compound synthesis (84,85) as seen by sporulation analysis. Many attempts have been made to improve the characteristics of Kyokai no. 7. Non-foaming mutants have been isolated from spontaneous clones as well as UV-induced mutants using selection methods such as cell agglutination and froth floatation (86). Improved strains have also been isolated through chemical mutagenesis (e.g., by EMS) to select for improved flavor profiles. In this case, mutant Kyokai no. 7 strains more resistant to cerulenin were thought to produce more ethyl caproate, an important flavor component. This approach was successful in improving this flavor component; however, the complete portfolio of complex phenotypes was not fully assayed (47). Finally, prevention of contaminants has been explored through mating sake yeast strains with strains exhibiting the killer phenotype (56), which would ward off contaminating yeasts. Collectively, these examples of complex phenotype engineering highlight the difficulties of the process, specifically; it is often hard to create all traits at once. The evolution of the sake yeast demonstrates the power of the classical approach. More recent attempts have been made to use the rational or evolutionary approach for this strain; however, Kyokai no. 7 remains the industrial favorite for sake production.

1.2 MUTAGENESIS

A fundamental parameter dictating success in classical strain engineering is the frequency and type of mutation applied to the parent cells. Typically, this rate is determined by the dose and type of mutagen delivered. To test mutagen specificity and rate, it is common to generate an inactive (mutant) form of some easily assayable gene (e.g., LacZ in E. coli) that differs from the wild-type gene by a single base-pair change, and test the frequency of reversion. For example, Cupples et al. generated six variants of LacZ to show that many common mutagens (EMS, NTG, 2-aminopurine, and 5-azacytidine) are in fact quite specific for certain base-pair changes in E. coli (4). Hampsey undertook a similar approach in S. cerevisiae and found similarly that mutagens were highly specific. However, the mutation frequencies and specificities were significantly different from those observed in E. coli (5). Frameshift and deletion frequencies can also be detected through analysis of a cleverly mutated marker (6). Through analyses of reversion frequencies or high-throughput sequencing, a detailed picture of a treatment’s mutagenic profile may be ascertained. This detailed information can be then be used to compute several useful quantities, such as the average number of mutations per genome or the expected number of distinct variants among a mutated population. Knowledge of these frequencies and landscapes are especially useful when designing a selection program, as detection of rare variants (e.g., individuals possessing certain particular mutations and no more) will require many individuals to be screened, whereas more probable patterns of mutagenesis (e.g., if additional silent or neutral mutations are tolerable) will not. At the same time, more focused patterns of mutation inherently limit the search space.

1.2.1 Numerical Considerations in Screen Design

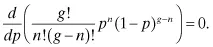

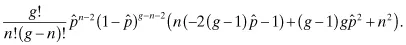

Although in general every possible base substitution will occur at a different frequency (and vary nonuniformly throughout the genome), it is instructive to neglect deletions or insertions and assume all base changes at each site are equiprobable (i.e., occur at the same frequency) to make use of the binomial distribution, to obtain approximate probabilities of any desired mutagenic outcome. If the probability of a single base being mutated to any other base is p, then the probability that a genome of size g has n mutations after mutagenesis is:

By using well-known properties of the binomial distribution, the average number of mutations per genome is gp with variance gp(1 − p). Random genetic drift results in mutation rates of 10−10 to 10−5, while forced mutagenesis can elicit rates upwards of 10−3 as described below, so this will restrict the range of p. It is apparent that if p is too low (that is, less than 1/g), there will be many variants with few or no mutations and a vanishingly small population of highly mutated individuals. Furthermore, the binomial coefficient indicates that libraries with low mutation rate (and thus a high population of slightly mutated individuals) are very likely to be redundant, that is, have many individuals of the same genotype. Thus, it is of interest to know the expected number of distinct variants in a mutant library to guide screen design. Patrick et al. developed a suite of algorithms to compute many quantities of interest for screening a mutant pool derived from a mutagenic procedure of arbitrary specificity, including the expected number of distinct mutants following mutagenesis (7,8). If the library is highly redundant, then screening of the entire mutated population may not be necessary to ensure complete coverage. As diversity increases, however, the required screening fraction will approach unity. Since complex phenotypes are controlled by the action of multiple genes, high mutation rates are often employed, generally resulting in high library diversity and a strong incentive to screen the entire mutated pool.

To choose the correct rate of mutagenesis and screening, it is important to know the rarity of the phenotype of interest. In the worst and most restrictive case, an improved phenotype will be acquired by mutants containing only a certain set of mutations. For example, consider a particular phenotype that only manifests itself when

n-specific mutations are present and no more. In this case, one must determine the mutation rate

which maximizes the fraction of

n-mutant variants in the mutated population (using one of the tools mentioned earlier) and screen until a reasonably high probability of complete coverage is achieved. For a genome of

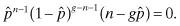

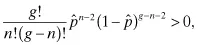

g base pairs, we can take the derivative of the binomial distribution with respect to mutation rate and set it equal to zero:

Eliminating constants and taking the derivative, we have:

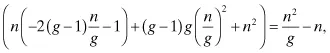

The obvious interesting candidate for a solution is:

Taking the second derivative of the binomial distribution yields:

Because

we can substitute our candidate solution into the remaining portion of the second derivative to determine its sign:

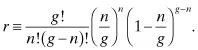

which is clearly negative for g > n. Hence, the likelihood of attaining n mutations in a genome of size g is maximized when the mutation rate is n/g. This maximum likelihood is:

It is generally necessary to screen more than the number of possible mutants to ensure coverage of the diversity. To obtain, on average, F fractional coverage of all n-mutant variants, it will be necessary to solve

for L, where a is the probability of selecting the correct n-mutant variant (1/V in this case, where V is the number of possible n-mutant variants [given by the binomial coefficient]) and L is the library size (7). For a small-sized genome (106 base pairs) and a phenotype requiring two specific mutations (hence at an optimal mutation rate of 2*10−6), L works out to be 5.5*1012...