- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Seismic Vulnerability of Structures

About this book

This book is focused on the seismic vulnerability assessment methods, applied to existing buildings, describing several behaviors and new approaches for assessment on a large scale (urban area).

It is clear that the majority of urban centers are composed of old buildings, designed according to concepts and rules that are inadequate to the seismic context. How to assess the vulnerability of existing buildings is an essential step to improve the management of seismic risk and its prevention policy. After some key reminders, this book describes seismic vulnerability methods applied to a large number of structures (buildings and bridges) in moderate (France, Switzerland) and strong seismic prone regions (Italy, Greece).

Information

Chapter 1

Seismic Vulnerability of Existing Buildings: Observational and Mechanical Approaches for Application in Urban Areas

1.1. Introduction

Past and recent earthquakes have shown the high level of seismic vulnerability of old and historic down-town areas: the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake is one of the latest dramatic examples, in which several historical centers (such as – besides L’Aquila – Onna, Castelnuovo and Villa Sant’Angelo) were severely affected, with heavy damage extended across whole built-up areas and the collapse of large portions (sometimes even in their totality) of many urban blocks. This follows the relevance of providing reliable vulnerability and risk analyses from the economic, cultural and human safety points of view.

As known, vulnerability represents the intrinsic predisposition of the building to be affected and suffer damage as a result of the occurrence of an event of a given severity. The main aims of a vulnerability analysis on a large scale – such as that of a town – are (1) to be aware of the impact of an earthquake to groups of buildings in the area; (2) to plan preventive interventions for the seismic risk mitigation; and (3) to help the management of the emergency after a major earthquake.

The main steps of a vulnerability analysis may be summarized as follows:

1) acquisition and examination of the data available in the area of interest, identification of building classes and definition of the related vulnerability models;

2) for each class, the definition of building parameters which models are based on; according to the data available, the parameters set can be single or differentiated for a micro-area;

3) partition of the territory into a number of zones, each characterized by a uniform hazard; disaggregation of the exposure data into different classes homogeneous for vulnerability;

4) for each building class and micro-area, evaluation of the performance point, fragility curves and damage probabilities (taking into account – less or more accurately – the uncertainties involved).

Vulnerability models are the tools to establish a correlation between a hazard and structural damage. As a function of the model adopted, a hazard may be represented in terms of the macroseismic intensity, peak ground acceleration (PGA) or the response spectrum. Structural damage is usually classified into various levels depending on the seriousness and extent in buildings; thus, building performance levels (PL) (i.e. immediate occupancy, damage control, safety to life and collapse prevention) may be associated with selected damage levels, on the basis of the consequences related to the advisability of post-earthquake occupancy, the risk to the safety of life or the ability of the building to resume its normal function. The structural damage is the cause of many other losses expected after an earthquake. Economic losses and consequences to buildings (unfit for use and collapsed buildings) and inhabitants (homelessness and casualties) can be estimated after physical damage has been determined. To this end, many statistical correlation laws, translating structural damage into percentage of losses, are proposed in the literature.

On a large scale, since usually the available data are not sufficient to define detailed models, vulnerability models cannot be applied building-by-building: thus, the vulnerability assessment has to refer to a building stock characterized by homogeneous behavior. In this sense, the evaluation assumes a statistical meaning that is consistent to the purposes of a risk analysis, that is to evaluate the probability having certain consequences on the examined area.

Several methods for the vulnerability assessment have been developed and proposed in recent years, which are implemented with the different kind of data (from poor statistical data about the building type and the number of floor to data specifically surveyed for seismic vulnerability assessment). They are based on various approaches, which may be basically classified according to the following two classes: the macroseismic (or observational) and the mechanical models.

Macroseismic models are derived and, consequently, calibrated from damage assessment data, collected after earthquakes in areas that suffered different intensities. Considering a set of buildings with a homogeneous behavior, damage is described by damage probability matrices (DPM); DPM traditionally are associated with a discrete number of building classes. Thus, the lack of information relative to damage grades for all levels of intensity, at a given geographical location or region characterized by a given building stock type, may lead to incomplete matrices; usually to complete the matrices for non-populated levels of damage and intensity binomial coefficients are used. In order to pass from discrete to continuous vulnerability evaluation, as proposed as an example in Giovinazzi and Lagomarsino [GIO 04], proper fragility curves may be introduced to correlate the intensity to the mean damage grade µD (a continuous parameter, 0 < μD < 5), and a histogram of damage grades is evaluated by a proper discrete probabilistic distribution (binomial). The fragility curve is defined by two parameters, the vulnerability index and a ductility index, which should be evaluated from the information about the building.

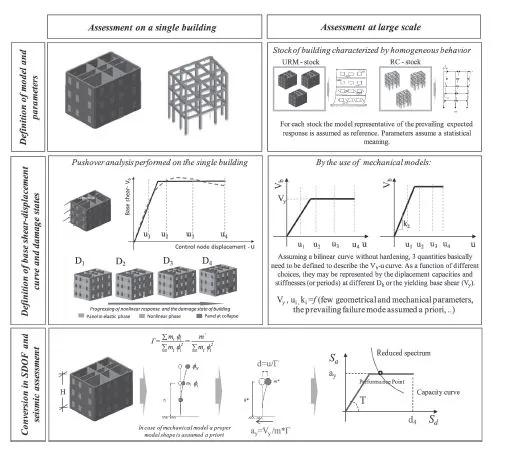

Mechanical models describe the structural response by means of a force–displacement curve, called capacity curve, representative of the equivalent inelastic single degree of freedom (SDOF) system; this curve provides essential information in terms of stiffness, overall strength and ultimate displacement capacity. In the case of vulnerability assessment at large scale, this curve aims to idealize the response of an entire stock of structures with homogeneous behavior. Assuming a bilinear form without hardening, three quantities basically need to be defined; different choices, as clarified in the following sections, may be adopted in selecting the independent and derived entities. This curve idealizes the response which could be achievable by subjecting the structure, idealized through an adequate model, to a static horizontal load pattern of increasing amplitude, aimed at describing the equivalent seismic forces: thus, it establishes a relationship between the demand and the structural capacity. Each point of this curve is associated with an exact pattern and level of damage (Figure 1.1). The expected damage assessment is provided by comparing the “capacity curve” with the “seismic demand”, in the form of a response spectrum (resulting from codes recommendations or more sophisticated hazard analyses). This approach is coherent with the current trend of nonlinear static procedures for the evaluation of the seismic performance of masonry buildings (e.g. the capacity spectrum method and the N2 Method). Finally, by defining proper damage levels (corresponding to predefined displacement values) on the capacity curve it is possible to evaluate the distribution of damage levels (and thus a mean damage index). The application to the large scale requires that these models are based on a limited number of geometrical and mechanical parameters. This need implies that mechanical models have to be in some way “simplified”; moreover, their application to the assessment of existing buildings, often designed following empirical rules of art (especially in the case of masonry constructions), may be in some cases conventional when the principles and rules of the design approach inspire the formulation of these models. An alternative for the definition of these curves could be by referring to detailed numerical analyses provided on prototype buildings, for which an accurate geometrical and mechanical characterization is available; however, the extrapolation of the results obtained on a single building to the entire corresponding stock may be quite conventional, with the drawback of not being able to exactly quantify the response variability associated with the uncertainties of parameters. Unlike the case of macroseismic models, which are calibrated on the basis of an earthquake damage survey, the validation of the mechanical models represents an issue much more complex since this direct comparison is not available. A possible alternative is to compare the results of the mechanical models to those provided by the macroseismic models; this comparison requires the introduction of suitable correlation laws between the parameters of the hazard (i.e. PGA and intensity).

Figure 1.1. Force–displacement curve obtained in case of pushover analysis performed on a single structure or by a mechanical model applied at large scale

A cross-validation of two approaches is proposed in Lagomarsino and Giovinazzi [LAG 06b].

Once the model adopted as the reference is defined, the first step of the above-mentioned methodology consists of processing the available data in order to aggregate them for homogeneous behavior classes and defining proper values for the model parameters (representative of each building class). Usually the following factors are considered: structural material (masonry and reinforced concrete, RC); structural system (i.e. pilotis; RC frame building, with or without infilled panels efficiently connected; masonry buildings with RC beams coupled to spandrel elements or with weak spandrels); number of stories; and age. In particular, the age is important for the choice of codes to assume as the reference in order to define the...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Contents

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Seismic Vulnerability of Existing Buildings: Observational and Mechanical Approaches for Application in Urban Areas

- Chapter 2: Mechanical Methods: Fragility Curves and Pushover Analysis

- Chapter 3: Seismic Vulnerability and Loss Assessment for Buildings in Greece

- Chapter 4: Experimental Method: Contribution of Ambient Vibration Recordings to the Vulnerability Assessment

- Chapter 5: Numerical Model: Simplified Strategies for Vulnerability Seismic Assessment of Existing Structures

- Chapter 6: Approach Based on the Risk Used in Switzerland

- Chapter 7: Preliminary Evaluation of the Seismic Vulnerability of Existing Bridges

- List of Authors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Seismic Vulnerability of Structures by Philippe Gueguen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Mechanical Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.