eBook - ePub

Copper-Catalyzed Asymmetric Synthesis

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Copper-Catalyzed Asymmetric Synthesis

About this book

This book reflects the increasing interest among the chemical synthetic community in the area of asymmetric copper-catalyzed reactions, and introduces readers to the latest, most significant developments in the field.

The contents are organized according to reaction type and cover mechanistic and spectroscopic aspects as well as applications in the synthesis of natural products. A whole chapter is devoted to understanding how primary organometallics interact with copper to provide selective catalysts for allylic substitution and conjugate addition, both of which are treated in separate chapters. Another is devoted to the variety of substrates and experimental protocols, while an entire chapter covers the use on non-carbon nucleophiles. Other chapters deal with less-known reactions, such as carbometallation or the additions to imines and related systems, while the more established reactions cyclopropanation and aziridination as well as the use of copper (II) Lewis acids are warranted their own special chapters. Two further chapters concern the processes involved, as determined by mechanistic studies. Finally, a whole chapter is devoted to the synthetic applications.

This is essential reading for researchers at academic institutions and professionals at pharmaceutical or agrochemical companies.

The contents are organized according to reaction type and cover mechanistic and spectroscopic aspects as well as applications in the synthesis of natural products. A whole chapter is devoted to understanding how primary organometallics interact with copper to provide selective catalysts for allylic substitution and conjugate addition, both of which are treated in separate chapters. Another is devoted to the variety of substrates and experimental protocols, while an entire chapter covers the use on non-carbon nucleophiles. Other chapters deal with less-known reactions, such as carbometallation or the additions to imines and related systems, while the more established reactions cyclopropanation and aziridination as well as the use of copper (II) Lewis acids are warranted their own special chapters. Two further chapters concern the processes involved, as determined by mechanistic studies. Finally, a whole chapter is devoted to the synthetic applications.

This is essential reading for researchers at academic institutions and professionals at pharmaceutical or agrochemical companies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Copper-Catalyzed Asymmetric Synthesis by Alexandre Alexakis, Norbert Krause, Simon Woodward, Alexandre Alexakis,Norbert Krause,Simon Woodward in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias físicas & Química orgánica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Primary Organometallic in Copper-Catalyzed Reactions

1.1 Scope and Introduction

In this chapter, the term primary organometallic will mean both the terminal organometallic (RM) selected for a desired asymmetric transformation and those Cu-species that result once the RM is combined with a suitable copper precursor. A significant advantage in copper-promoted chemistry is the ability to access a very wide library of M[CuXRLn] species (M, main group metal; X, halide or pseudohalide; R, organofunction; L, neutral ligand) by simple variation of the admixed reaction components. Normally, the derived cuprate mixture is under rapid equilibrium such that if one species demonstrates a significant kinetic advantage, highly selective reactions can be realized. The corollary to this position is that deconvoluting the identity of such a single active species from the inevitable “soups” that result from practical preparative procedures can prove highly challenging. In this review, we concentrate on asymmetric catalytic systems developed in the last 10 years, but where necessary, look at evidence from simpler supporting achiral/racemic cuprates. Our aim is to try and present a general overview of bimetallic (chiral) cuprate structure and reactivity. However, given this extremely wide remit, the coverage herein is necessarily a selective subset from the personal perspective of the author. There are a number of past books of general use (either totally or in part) that provide good primers for this area [1]. Additionally, because of its relevance the reader is advised to also consult Chapter 12, which deals with mechanism.

1.2 Terminal Organometallics Sources Available

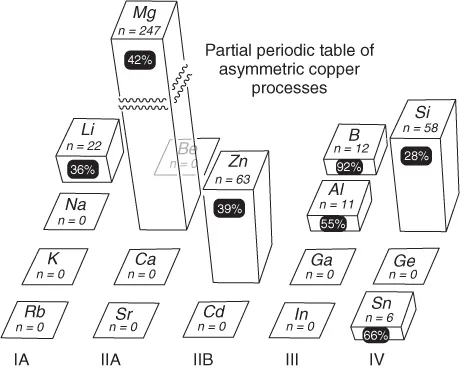

One partial representation of the totality of asymmetric processes promoted by copper and main group organometallic mixtures is given in Figure 1.11; where the height of the bar indicates published activity (n = number of papers, etc.) and the percentage in the black roundel is the fraction published in the last 5 years (2007–2012).

Figure 1.1 Approximate relative use (n) of group II–IV organometallics in copper-promoted asymmetric processes, and percentage increase of activity over 2007–mid 2012 (black roundels)1).

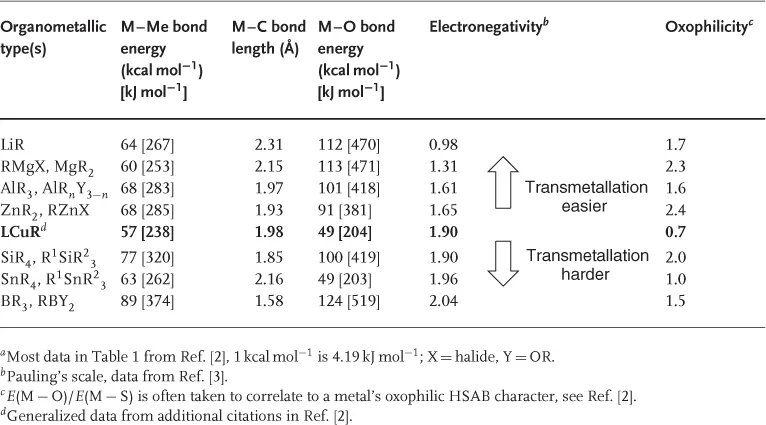

The seven metals identified (Li, Mg, Zn, B, Al, Si, and Sn) form the basis of this overview. It should be noted that (i) the dominance of magnesium is due to numerous simple addition reactions where the resultant stereochemistry is controlled only by a chiral substrate; (ii) asymmetric reactions of the organometallics of the lower periods are still largely unreported; (iii) while all areas have developed, there has been especial interest in some metalloids in recent years (e.g., organoboron reactions); and (iv) the use of silicon organometallics is over reported in Figure 1.1 by the extensive use of silanes as reducing agents. The general properties of the organometallics used in asymmetric copper-promoted reactions are given in Table 1.1, compared with a generalized LCuR fragment. A common feature is their tendency to form strong bonds with oxygen, providing strong thermodynamic driving forces for additions to carbonyl-containing substrates. This tendency can be correlated to their relatively low electronegativities and high oxophilicities (“hardness” defined here as E(M − O)/E(M − S)]. The published Sn–O bond energy, derived from density functional theory (DFT) calculation, is probably somewhat underestimated in this respect. The reactivity of main group organometallics in Table 1.1 is reinforced by their weak M–C bonds. In fact, M–Me values are often upper limits – the bond energies of the higher homologs are frequently lower by 5–10 kcal mol−1 meaning that in mixed R1MMen the methyls can be used as a potential nontransferable groups. Similarly, significant increases in the reactivity of organoelement compounds across the series M(alkyl), M(aryl), and M(allyl) are observed. At least in the allyl case, this is correlated to the M–C bond strength, which is typically >10 kcal mol−1 lower than M–Me.

Table 1.1 Properties of main group organometallics used in asymmetric Cu-promoted processes in order of element electronegativity.a

1.3 Coordination Motifs in Asymmetric Copper Chemistry

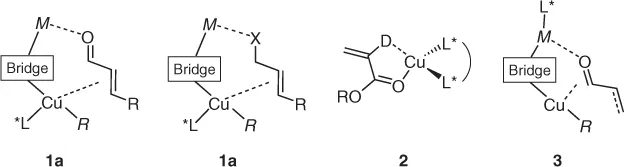

Copper-promoted asymmetric reactions frequently attain high enantioselectivity through reduction in substrate conformational mobility via two-point binding, as in the general copper(I) cuprates 1a,b or by η2-binding at chiral CuII complexes, generalized by 2 (Scheme 1.1). As copper(II) does not form organometallic species, and readily undergoes reduction to CuI in the presence of RM, we concentrate here mainly on the former (overviews of activation by 2 can be found through the work of Rovis and Evans [4]). One other common scenario is use of a chiral Lewis acid fragment linked to a simple heterocuprate via a bridging ligand 3.

Scheme 1.1 Generalized binding modes for Cu-promoted activation of prochiral substrates where MR is a main group organometallic, X is a halogen, D is a generalized two electron donor, and “bridge” is a generalized anionic ligand. Extension to analogous isoelectronic fragments (e.g., NR for O, etc.) is, of course, possible.

Clearly, in attaining enantioselective transition states for asymmetric reactions, the nature of the bridging ligand (typically a halide or pseudohalide) is at least as important as the identification of an effective chiral ligand (L*) in attaining effective docking of substrates in 1–3.

1.3.1 Classical Cuprate Structure and Accepted Modes of Reaction

1.3.1.1 Conjugate Addition

Owing to their initial discovery, an enormous degree of activity has focused on the structures and reactivity of the Gillman-type homocuprates (LiCuR2) and their heterocuprate analogs (LiRCuX, where X is the halide of pseudohalide [5]). In general, while these systems have provided underlying understanding of the basics of copper(I)/copper(III) organometallic chemistry they have not directly provided reagents that give highly selective catalytic asymmetric methodology. It is instructive to ask, “Why is this the case?” – a question that modern computational DFT understanding of the reaction course can cast light on. In classic conjugate addition, dimeric [LiCuMe2]2 reacts with cyclohexenone via transition state 4 [6], in which the enone-bound copper is formally at the +3 oxidation state (Scheme 1.2). One issue is that coordination of the d8 CuIII center with an additional neutral chiral ligand (e.g., a phosphine) has to compete with excess strong σ-ligands in the solution (e.g., Me−), and also from intramolecular donation from the enolate π-bond (which renders the Cu-center coordinatively saturated). Another issue is associated with the lability of any ([R–Cu–R]Li)n bridge. Although Li–O contacts in organocuprates are essentially covalent, an ionic formulation for 4 has been used here to emphasize the propensity of such units to exchange and associate. Such behavior is nicely demonstrated by the diffusion NMR studies of Gschwind [7], which measure the “size” of cuprates in solution allowing estimations of their identities. These studies show how easily cuprate-based bridges are readily displaced by tetrahydrofuran (THF) (leading to a catastrophic enone inactivation by loss of the Oenone···Li Lewis acid contact) or, alternatively, promotion of multiple species through aggregation of 4 in less polar solvents. This ease of displacement of homocuprate bridging groups by “lithium-liking” pseudohalides (e.g., alkoxide impurities in RLi or derived from halides in CuX precursors) s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Primary Organometallic in Copper-Catalyzed Reactions

- Chapter 2: Copper-Catalyzed Asymmetric Conjugate Addition

- Chapter 3: Copper-Catalyzed Asymmetric Conjugate Addition and Allylic Substitution of Organometallic Reagents to Extended Multiple-Bond Systems

- Chapter 4: Asymmetric Allylic Alkylation

- Chapter 5: Ring Opening of Epoxides and Related Systems

- Chapter 6: Carbon–Boron and Carbon–Silicon Bond Formation

- Chapter 7: CuH in Asymmetric Reductions

- Chapter 8: Asymmetric Cyclopropanation and Aziridination Reactions

- Chapter 9: Copper-Catalyzed Asymmetric Addition Reaction of Imines

- Chapter 10: Carbometallation Reactions

- Chapter 11: Chiral Copper Lewis Acids in Asymmetric Transformations

- Chapter 12: Mechanistic Aspects of Copper-Catalyzed Reactions

- Chapter 13: NMR Spectroscopic Aspects

- Chapter 14: Applications to the Synthesis of Natural Products

- Index