![]()

Part One

Conflict

![]()

Chapter One

The Nature of Conflict

Note: All of the examples from my own practice either are from public, nonconfidential forums or are heavily disguised to protect confidentiality.

We are of two minds about conflict. We say that conflict is natural, inevitable, necessary, and normal, and that the problem is not the existence of conflict but how we handle it. But we are also loath to admit when we are in the midst of conflict. Parents assure their children that the ferocious argument the parents are having is not a conflict, just a “discussion.” Organizations hire facilitators to guide them in strategic planning, goal setting, quality circles, team building, and all manner of training, but they shy away from asking for help with internal conflicts. Somehow, to say we are in conflict is to admit failure and to acknowledge the existence of a situation we consider hopeless.

This ambivalence about conflict is rooted in the same primary challenge conflict interveners face—coming to terms with the nature and function of conflict. How we view conflict affects our attitude toward it and our approach to dealing with it, and there are many ways of viewing it. For example, we may think of conflict as a feeling, a disagreement, a real or perceived incompatibility of interests, a product of inconsistent worldviews, or a set of behaviors. If we are to be effective in handling conflict, we must start with a way to make sense of it and to embrace both its complexity and its essence. We need tools that help us separate out the many complex interactions that make up a conflict, that help us understand the roots of conflict, and that give us a reasonable handle on the forces that motivate the behavior and interaction of all participants, including ourselves.

Whether we are aware of them or not, we all enter conflict with assumptions about its nature. Sometimes these assumptions are helpful to us, but at other times they are blinders that limit our ability to understand what lies behind a conflict and what alternatives may exist for dealing with it. We need frameworks that expand our thinking, challenge our assumptions, and are practical and readily usable. As we develop our capacity to understand conflict in a deeper and more powerful way, we enhance our ability to handle it effectively and in accordance with our most important values about building peace. To simplify the task of handling complex conflicts, we need to complicate our thinking about conflict itself.

A framework for understanding conflict should be an organizing lens that brings a conflict into better focus. There are many different lenses we can use, and each of us will find some more amenable to our own way of thinking than others. Moreover, the lenses presented in this chapter are not equally applicable to all conflicts. Seldom would we apply all of them at the same time to the same situation. Nevertheless, together they provide a set of concepts that can help us understand the nature of conflict and the dynamics of how conflict unfolds.

How We Experience Conflict

Conflict emerges and is experienced along cognitive (perception), emotional (feeling), and behavioral (action) dimensions. We usually describe conflict primarily in behavioral terms, but this can oversimplify the nature of the experience. Taking a three-dimensional perspective can help us understand the complexities of conflict and why a conflict sometimes seems to proceed in contradictory directions.

Conflict as Perception

As a set of perceptions, conflict is our belief or understanding that our own needs, interests, wants, or values are incompatible with someone else’s. There are both objective and subjective elements to this dimension. If I want to develop a tract of land into a shopping center and you want to preserve it as open space, then there is an objective incompatibility in our goals. If I believe that the way you desire to guide our son’s educational development is incompatible with my philosophy of parenting, there is a significant subjective component. If only one of us believes an incompatibility to exist, are we still in conflict? As a practical matter I find it useful to assume that a conflict exists if at least one person thinks that there is a conflict. If I believe that we have incompatible interests and proceed accordingly, I am engaging you in a conflict process whether you share this perception or not. The cognitive dimension is often expressed in the narrative structure that disputants use to describe or explain a conflict. If I put forward a story about an interaction that suggests that you are trying to undercut me or deny me what is rightfully mine, I am both expressing and reinforcing my view about the existence and nature of a conflict. The narratives people use provide both a window into the cognitive dimension and a means of working on the cognitive element of conflict.

Conflict as Feeling

Conflict is also experienced as an emotional reaction to a situation or interaction. We often describe conflict in terms of how we are feeling—angry, upset, scared, hurt, bitter, hopeless, determined, or even excited. Sometimes a conflict does not manifest itself behaviorally but nevertheless generates considerable emotional intensity. As a mediator, I have sometimes seen people behave as if they were in bitter disagreement over profound issues, yet been unable to ascertain exactly where they disagreed. Nonetheless, they were in conflict because they felt they were. As with the cognitive dimension, conflict on the emotional dimension is not always experienced in an equal or analogous way by different parties. Often a conflict exists because one person feels upset, angry, or in some other way in emotional conflict with another, even though those feelings are not reciprocated by or even known to the other person. The behavioral component may be minimal, but the conflict is still very real to the person experiencing the feelings.

Conflict as Action

Conflict is also understood and experienced as the actions that people take to express their feelings, articulate their perceptions, and get their needs met, particularly when doing so has the potential for interfering with others’ needs. Conflict behavior may involve a direct attempt to make something happen at someone else’s expense. It may be an exercise of power. It may be violent. It may be destructive. Conversely, this behavior may be conciliatory, constructive, and friendly. Whatever its tone, the purpose of conflict behavior is either to express the conflict or to get one’s needs met. Here, too, there is a question about when a conflict “really” exists. If you write letters to the editor, sign petitions, and consult lawyers to stop my shopping center and I don’t even know you exist, are we in conflict? Can you be in conflict with me if I am not in conflict with you? Theory aside, I think the practical answer to both of these questions is yes.

In describing or understanding conflict, most of us gravitate first to the behavioral dimension. If you ask disputants what a conflict is about, they are most likely to talk about what happened or what they want to happen—that is, about behavior. Furthermore, any attempt to reach an agreement will naturally focus on behavior because that is the arena in which agreements operate. We can say we agree to try to feel differently or to think differently about something—and such statements are often built into agreements—but they are generally more aspirational than operational. What we can agree about is behavior: action or inaction. When we focus on arriving at outcomes it is natural for us to emphasize this dimension at the expense of the others, but in doing so we may easily overlook critical components of the conflict and the work necessary to address its cognitive and emotional elements.

Obviously the nature of a conflict on one dimension greatly affects how it plays out and is experienced on the other two dimensions. If I believe you are trying to hurt me in some way, I am likely to feel as though I am in conflict with you, and I am apt to engage in conflict behaviors. None of these dimensions is static. People move in and out of conflict, and the strength or character of conflict along each dimension can change rapidly and frequently. And even though each of the three dimensions affects the others, a change in the level of conflict on one dimension does not necessarily cause a similar change on the other dimensions. Sometimes an increase on one dimension is associated with a decrease on another. For example, the emotional component of conflict occasionally decreases as people increase their awareness of the existence of the dispute and their understanding of its nature. This is one reason why conflict can seem so confusing and unpredictable.

What about a situation in which no conflict perceptions, emotions, or behaviors are present but in which a tremendous potential for conflict exists? Perhaps you are unaware of my desire to build a shopping center, and I am unaware of your plans for open space. Are we in conflict? We may soon be, but I believe that until conflict is experienced on one of the three dimensions it is more productive to think in terms of potential conflict than actual conflict. The potential for conflict almost always exists among individuals or institutions that interact. Unless people want to think of themselves as constantly in conflict with everyone in their lives, it is more useful to view conflict as existing only when it clearly manifests itself along one of the three dimensions.

As well as individuals, can social systems—families, organizations, countries, and communities—be in conflict, particularly along the emotional or cognitive dimensions? Although there are some significant dangers to attributing personal characteristics or motivational structures to systems, practically speaking, systems often experience conflict along all three dimensions. We tend to use different terms, such as culture, ethos, organizational values or family values, public opinion, or popular beliefs, to characterize the greater complexity and different nature of the emotional and cognitive dimensions in social systems, but we intuitively recognize that group conflict has cognitive and emotional as well as behavioral dimensions. Is there an emotional and a perceptual aspect to the conflict between Iran and the United States or between Israel and Palestine? Of course, and we cannot understand the nature of these conflicts if we do not deal with these aspects. This does not mean that every individual member of each country shares the same feelings or perceptions, or even that a majority do. It means instead that the conflict evokes certain reactions and attitudes from a significant number of people in each society. Similarly, when we look at conflicts between union and management, environmental groups and industry associations, progressives and conservatives, it is important to understand the attitudes, feelings, values, and beliefs that these groups have concerning each other if we are to understand what is occurring.

How we describe a conflict usually reflects how we are experiencing it. The same conflict or concerns can be described using the language of feeling (“I feel angry and hurt”), perception (“I believe you are completely missing the point and do not have a clue about this”), or action (“I want you to do this or I will have to take further action”). Frequently, in observing people in conflict, we can see that one party may be using the language of feeling and the other the language of perception, and this alone can exacerbate a conflict. There are in fact several inventories of conflict styles that focus on this (for example, the Strength Deployment Inventory on the Personal Strengths, USA Web site, “SDI,” n.d.).

How conflict is experienced by one party is closely intertwined with how others experience it. Although one party may be more likely to express and react to the emotional dimension, for example, and another party may be more attuned to the behavioral dimension, their approaches affect each other. For example, if one party describes and experiences a conflict in emotional terms, other parties may gravitate toward this dimension, thereby reinforcing the way the first party experiences the conflict. Or they may be encouraged to take a more cognitive approach by way of reaction. How parties cocreate their experiences of a conflict is an essential part of the conflict story.

By considering conflict along the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions, we can begin to see that it does not proceed along one simple, linear path. When individuals or groups are in conflict, they are dealing with complex and sometimes contradictory dynamics in these different dimensions, and they behave and react accordingly. This accounts for much of what appears to be irrational behavior in conflict. Consider this typical workplace dispute:

This kind of result is not unusual in conflict, and it can cause people to behave in apparently inconsistent ways because on one dimension the conflict has been dealt with, but on another dimension it may actually have gotten worse. Thus the employees in this example may cease their overtly conflictual behavior, but the tension between them may actually increase.

What Causes Conflict?

Conflict has multiple sources, and theories of conflict can be distinguished from one another by which origin they emphasize. Conflict is seen as arising from basic human instincts, from competition for resources and power, from the structure of the societies and institutions people create, from flawed communication, and from the inevitable struggle between classes. Although most of these theories offer valuable insights and perspectives on conflict, they can easily point us in different directions as we seek a constructive means of actually dealing with conflict. What we need is a practical framework that helps us use some of the best insights of different conflict theories.

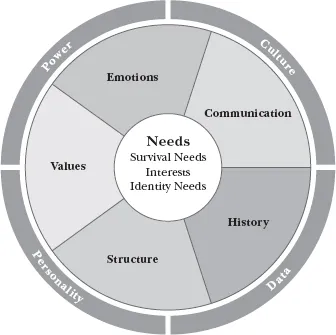

If we can understand and locate the sources of conflict, we can create a map to guide us through the conflict process. When we understand the different forces that motivate conflict behavior, we are better able to create a more nuanced and selective approach to handling conflict. Different sources of conflict produce different challenges for conflict engagement. The wheel of conflict, illustrated in Figure 1.1, is one way of understanding the forces that are at the root of most conflicts. This conceptualization of the sources of conflict arose out of my work as a conflict practitioner and conversations with colleagues at CDR Associates and elsewhere, and it is derivative of the circle of conflict developed by Christopher Moore (2003). Moore’s circle consists of five components: relationship problems, data problems, value differences, structural problems, and interests. This has proven a valuable tool for analyzing the sources of conflict, but I have chosen to rework it to reflect a broader view of human needs and the issues that make it hard for us to directly address these needs.

Human needs are at the core of all conflicts. People engage in conflict either because they have needs that are met by the conflict process itself or because they have needs that they can only attain (or believe they can only attain) by engaging in conflict. I discuss the system of human needs in detail later in this chapter. My point here is that people engage in conflict because of their needs, and conflict cannot be transformed or resolved unless these needs are addressed in some way. We should not understand needs as static and unchanging. We all have a range of needs, but how we experience these is influenced by the context and the unfolding interaction. For example, I might start negotiating to sell a house mostly concerned about money, timing, and certainty, but if the hard work I have done to remodel my home is dismissed as sloppy or in poor taste, then I might suddenly find myself more concerned with issues of identity, pride, and self-image. In this way, the needs we experience are constantly evolving and changing as we interact with others.

Needs are embedded in a constellation of contextual factors that generate and define conflict. To effectiv...