![]()

1 Studying Law and Courts

Lee Epstein

In the 1963 case of School District of Abington Township v. Schempp, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment to the Constitution prohibits prayer and Bible-reading exercises in public school. This ruling was immensely controversial. Many public schools throughout the United States—but especially in the South—had historically engaged in some form of prayer in school. The public outcry against Schempp was so great that members of Congress immediately introduced nearly 150 proposals to overturn the decision.

Given the hostile political environment surrounding the Court’s pronouncement, a natural question arises: Did school districts comply with Schempp? In his textbook The Supreme Court, the political scientist Lawrence Baum (1992b, 214) provides one answer when he writes that “[w] ithin three years . . . the frequency of school prayer and Bible readings had declined by about one-half; . . . this decline is noteworthy. But equally striking is the continuation in so many schools of practices that the Supreme Court had declared to be unconstitutional.”

Although Baum’s statement provides useful information about public response to Schempp, it points to an interesting question: How does Baum know that only about one-half of all schools complied with the Court’s rulings? To put the question more generally, from where do the authors of textbooks obtain the facts and figures that populate their works? The answer to these questions is quite simple. Usually textbook writers rely on studies conducted by other researchers working in their field. In making the claim about the effect of the school prayer decisions, for example, Baum cited a study by H. Frank Way, Jr. (1968), who surveyed school districts and found that compliance was occurring in only about half.

From this perspective we can begin to understand the importance of research. The most obvious benefit is the useful information that scholarly studies provide to society. The results of Way’s survey, for instance, highlight the Supreme Court’s lack of power to enforce its decisions; it may be unable to generate compliance with its rulings if we—the people—reject them. Somewhat less obvious, though, is the role played by research and how it influences what instructors teach and what students learn. It was Way’s study of prayer in school that enabled Baum to write about compliance with the Court’s decision. And it is Baum’s textbook, not necessarily Way’s study, that instructors assign to their students to read.

This point—that an intimate link exists between research and teaching—is often obscured in debates that pit one against the other. We have all heard the voices of the commentators who complain that professors spend too much time conducting research and too little teaching students. Without denying the validity of these claims, I would say that at the very least they set up a false and unfair dichotomy. As the Way-Baum connection illustrates, much of what scholars teach and students learn comes from research. The converse is true as well. Students, through their questions, often generate research ideas. My own experience bears this out. While I was teaching a course on defendants’ rights, a student asked me a penetrating question about the death penalty. When I found I could not supply a definitive answer, I asked one of my colleagues the question. He, in turn, suggested that we conduct some research to derive a solution. We did, and a book that I now use in that very class (Epstein and Kobylka 1992) resulted.1

As readers can probably tell, I have strong feelings about the relation between teaching and research, feelings that occasionally run counter to fashionable commentary. The purpose of this book, however, is not to provide an abstract response to those who set teaching against research. Rather, by example it lends support to their interrelatedness. In each chapter, authors raise significant substantive questions and address them through appropriate analytic research strategies. One of the goals of the book is to bring the research process to students and instructors directly, not by the usual route of researcher to textbook writer to student (for example, Way to Baum to student).

A second and related objective is to give students some sense of the mechanics behind conducting research. Undergraduates, in particular, often see their professors furiously typing something into a computer or sifting through various collections in the library. But they have little idea about what they are up to or about the research process.

The contributors to this book provide a window to this process by exploring specific topics related to law and courts. Jeffrey A. Segal, Donald R. Songer, and Charles M. Cameron, for example, consider the relation between lower and upper appellate courts; Richard Pacelle examines the marked change in the Supreme Court’s agenda; and so on. In what follows, I take a more general course. I outline the research process, leaving the details up to the essayists to fill in.

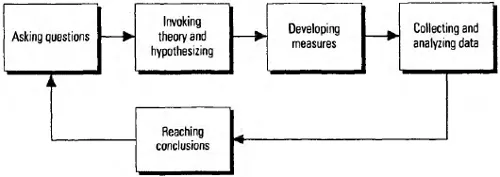

Figure 1-1 The Research Process

Sources: Bernstein and Dyer 1984, 3: Williamson et al., 1982, 7.

An Outline of the Research Process

The social-scientific research process is not a monolith; instead, it reflects the diversity of theoretical and substantive interests of the various disciplines. Consider the contributions to this volume. All the authors are concerned with issues relating to law and courts, but a mere glance at their essays attests to the pluralism of approaches. For example, although the contributions of Harold J. Spaeth and Leslie Friedman Goldstein both concentrate on judicial decision making, they ask very different questions. Spaeth considers how judges decide cases; Goldstein asks how they should decide cases. The subtle but crucial difference in the wording of their questions gives rise to divergent research strategies: Spaeth takes a data-intense approach, and Goldstein takes a more contextual one.

For all the differences, however, patterns exist. Virtually all research on law and courts—and, for that matter, on political and social phenomena more generally—shares some common features. Studies tend to (1) focus on specific research questions, (2) invoke theories to provide initial answers (or predictions), (3) develop ways (or measures) to turn predictions into testable hypotheses, and (4) examine the hypotheses against observable facts to reach some conclusions. Figure 1-1 provides a visual description of this process; below, I consider each of these features, with emphasis on their relation to legal social scientific scholarship.2

Asking the Question

Almost all research starts with a basic question or set of questions to which the scholar wants to learn the answer. In the field of law and courts, questions can be as broad in scope as, What factors generate crime in the United States? to ones more narrowly focused, such as, Does the death penalty serve to deter murder? They can center on aggregates (Why does the Supreme Court vote the way it does?) or individuals (Why does Chief Justice Rehnquist vote the way he does?). And they may be focused on events occurring at a specific point in time (What explains the senators’ votes in the confirmation proceedings for Robert Bork in 1987?) or over time (What explains senators’ votes in confirmation proceedings between 1900 and 1994?).

How do scholars select their research questions? An important factor is interest. Scholars, like all people, are interested in some topics more than others. And since research questions are a way to narrow a topic, it is not too surprising that scholars focus on things that interest them. Suppose I am intrigued by the relationship between international crises and judicial decision making in cases concerning civil liberties. If that is my interest, I might then narrow my question to something along these lines: Are jurists more likely to repress rights and liberties during times of war?

Another, related factor is curiosity. Many things can lead scholars to become curious about particular phenomenon. When my student asked me the question about the death penalty that I could not answer, I became curious—almost insatiably so—about the appropriate response. Curiosity can also emerge from discrepancies between what scholars think they know and what they observe. To return to the issue of war and liberties, I thought I knew the answer to the question posed above: according to research by Jeffrey A. Segal and Harold J. Spaeth (1993), external events, such as wars and international crises, should not influence judicial rulings unless the litigation itself deals with such events. That is because justices base their decisions on the facts of cases in light of their own ideological attitudes and values. They are “single-minded seekers of legal policy” whose ideology dictates their votes. Or, as Segal and Spaeth (1993, 65) put it, “Rehnquist votes the way he does because he is extremely conservative; Marshall voted the way he did because he is extremely liberal.” Thus, this view—what Segal and Spaeth label an attitudinal approach—leaves no room for external events, such as wars, that are not explicitly part of the facts of the case; in general, Rehnquist will take the conservative position and Marshall will take the liberal one, regardless of whether or not a war is occurring.3

Although the logic invoked by Segal and Spaeth seems to make sense, I became troubled by the presence of certain “facts” that do not sit comfortably with their explanation. For one thing, the justices have implied that they, like “all citizens . . . both in and out of uniform, feel the impact of war in greater or lesser measure” (Korematsu v. United States 1944). According to some scholars (for example, Emerson 1970), this kind of statement is suggestive. It implies that the Court thinks of cases—even those unrelated to the war effort—differently during times of war and peace. There is yet another piece of the puzzle that did not add up to me. That is, analysts (for example, Dahl 1957) have long argued that as part of the ruling regime, the Court usually upholds the interests of the majority, a phenomenon that may be even more attenuated during times of crisis or when national security interests are at stake. Under this view, the initiation of crisis conditions jolts the Court into the necessity of being more sensitive to the interests and wishes of the public and other government institutions. The discrepancy between the explanation of Segal and Spaeth and these “facts” only heightened my curiosity; I became genuinely puzzled.

Theorizing about Possible Answers

Once scholars hit upon questions they find interesting or about which they are curious, the next step is to think about possible answers, which can be used to generate predictions or expectations. Where do scholars find these potential answers?

Sometimes they discover them in the scholarly literature; they scrutinize the results of past research and apply them to their problem. That is why most academic publications, including many of the chapters in this book, include reviews of the relevant literature. For example, in thinking about decision making during times of war, I would want to know if any other scholar had attempted to answer precisely the same question. And, in fact, a search I conducted of journals and books turned up several studies directly on point. The System of Freedom of Expression, by Emerson (1970), for one, provides a descriptive analysis of cases decided before and after periods of threat to the nation’s external security. Emerson finds that the Court is more likely to repress rights and liberties when the United States is at war, even in cases unrelated to the particular international crisis.

Emerson’s work provides me with valuable leverage on my specific research problem. And I certainly would mention the study in my literature review. But since social scientists strive to produce general explanations, more often than not they seek broader answers to their research questions. That is why we turn to “theories.” In the context of social science research, theories are sets of “principles” that provide us insight into why actors behave the way they do (see Williamson et al. 1982). Scholars often use these insights to develop crisp expectations about the relations that intrigue them.

By way of illustration, reconsider the object of my interest: the relation between war and judicial decision making. How might I use theory to inform my research? I would start by identifying appropriate theories, those that speak to the issue of political decision making. Then, I would use those theories to generate expectations about the relationship between war and judicial decisions in civil liberties cases. For my research, I would have no trouble in finding such theories, since scholars in political science have paid a good deal of attention to the subject of decision making. We already know about one such theory—the attitudinal approach offered by Segal and Spaeth—and the expectations about the relationship between war and judicial decision making that it would generate (that is, there would be no relation independent of the facts of the case). But there are others. Many rational choice theories of judicial decision making, for example, begin with the same assumption as Segal and Spaeth—that justices are goal-directed, single-minded seekers of legal policy (Eskridge 1991a and 1991b). But, unlike Segal and Spaeth, choice theories of judicial decisions emphasize that these goal-directed actors operate in strategic or independent decision-making context: the justices know that their “fates” depend on the preferences of other actors—such as Congress, the president, and their colleagues—and choices they expect these other actors to make, not just on their own actions (Ordeshook 1992, chap. 1).4 This notion of interdependent choice is important for the following reason. If justices really are single-minded seekers of legal policy, then they necessarily care about the “law,” broadly defined. And if they care about the ultimate state of the law—about generating policy that other institutions will not overturn—then they must act strategically, taking into account the preferences of others and the actions they expect others to take. Occasionally, such calculations will lead them to act in a sophisticated fashion (that is, in a way that does not reflect their sincere or true preferences) so as to avoid the possibility of seeing their most preferred policy rejected by their colleagues in favor of their least preferred one, of Congress replacing their preference with its own, of political noncompliance, and so forth (Murphy 1964; Rodriguez 1994).

If we adopt this rational choice theory, then we would obtain a prediction about the relationship between war and judicial decision making very different from the one generated by Segal and Spaeth. Suppose Justice X were to select among three possible outcomes in an ordinary criminal case, unrelated to any war effort. Further suppose that Justice X preferred outcome 1 to 2 and outcome 2 to 3. In such a case, we would posit that the attitudinal Justice X would always choose outcome 1, regardless of whether or not America was fighting a war, while the strategic Justice X might choose outcome 2 if—depending on the political context (for example, a time of war), the preferences of the political actors involved (for example, Congress), and the actions those actors are expected to take—that would allow her to avoid outcome 3. In other words, while Segal and Spaeth’s attitudinal theory posits that no relation will exist between judicial decisions and wars (unless, of course, the war is part of the case facts), the rational choice view of the Court suggests that a relationship could emerge, depending on the preferences of the key political actors and the actions they are expected to take.

In the pages that follow, students will see how other researchers invoke various theories to guide their research, to help them to formulate expectations about the relations under investigation. In many of these chapters, ho...