![]()

1 Introduction

We are faced with hundreds of decisions every day. We chose when to get up this morning, what clothing we would wear, and even whether to read this book. Most of the consequences of the decisions we make throughout our day are relatively trivial or inconsequential. It probably didn’t matter too much if we decided to sleep an extra 15 minutes this morning or if we selected the blue shirt rather than the green one. However, some of the decisions we make can carry substantial consequences. Choosing to get an undergraduate or graduate degree, deciding on a new job or career, or selecting one vendor out of many candidates to be our company’s long-term supplier of a necessary resource are important decisions that are likely to have a significant and meaningful impact on our lives. Learning, understanding, and applying critical thinking and creative problem-solving skills can improve the quality of the decisions that mean the most to us.

Many of our decisions don’t need much thought. Relatively small, routine, or mundane choices generally don’t require us to spend a lot of time or energy because the outcomes associated with these types of decisions probably don’t affect us very much. In other cases, however, we need to spend time to think about our decisions, especially those related to solving problems.

Important decisions can shape our lives, and our decision quality is improved if we critically and creatively analyze the problems facing us by considering new and different options, weighing the evidence objectively, looking at a problem from a different angle that gives us different insights, developing novel solutions that effectively solve our dilemmas, and accurately forecasting the probable impact of our decisions.

To think critically and solve problems creatively, we must first understand how decisions are made and the factors influencing our decision-making processes. Much of what is taught through formal education concerns how decisions should be made. Although an understanding of rational decision making helps to explain decisional processes, behavioral decision theory is concerned with how people actually do make decisions. If we as decision makers are aware of the factors influencing both our interpretation of problems and the methods we use to solve them, then we are better able to see subjective patterns of behavior in our own decision actions and take steps to minimize and avoid their possible negative impact on what we decide. If we are aware of how the mind processes information and how biological, physiological, and psychological factors influence thinking, we are better prepared to address their probable influence on our decisions. And if we are aware of conceptual blocks that hinder our creativity and innovation, then we are better able to overcome their constraining effects and unleash the creative potential in our minds.

Do you have trouble making decisions? If so, you’re not alone. Most of us find decision making difficult, as the list in Table 1.1 demonstrates. This book distills what behavioral science has discovered related to how people, especially those in business, make decisions. Findings presented here are derived from supportive research representing what we currently know about decision making and problem solving. The information presented in the following chapters should enable decision makers to recognize and focus on the truly important decisions that require critical thinking, to analyze options more clearly and creatively, to reduce decisional time and effort, and to improve judgment quality. Awareness and application of the material contained here not only will enable us to improve our own decisions, but also will provide the means for us to understand how and why others decide as they do.

Critical thinking is a process that emphasizes a rational basis for what we believe and provides standards and procedures for analyzing, testing, and evaluating our beliefs (Rudinow & Barry, 1994). Critical thinking skills enable decision makers to define problems within the proper context, to examine evidence objectively, and to analyze the assumptions underlying the evidence and our own beliefs. Critical thinking enables us to understand and deal with the positions of others and to clarify and comprehend our own thoughts as well. When critical thinking is applied, all aspects of the decision process are involved, from defining the problem, identifying and weighing decision criteria, and generating and evaluating alternatives to estimating the consequences that will result from our decisions. However, critical thinking does not mean that we always make the best possible decision, never reach the wrong conclusion, and never make mistakes; it is simply a process we apply that enables us to arrive at superior decisions consistently.

TABLE 1.1 Decision-Making Difficulty

| Type of Decision | Percentage of People Who Have Trouble Making This Type of Decision |

| Making political choices | 76 |

| Buying life insurance | 73 |

| Choosing the best school for their children | 72 |

| Buying a new car | 71 |

| Selecting clothing to wear | 63 |

| Planning how to lose weight | 61 |

| Choosing a doctor | 55 |

| Deciding where to vacation | 52 |

SOURCE: Data are drawn from U.S. News and World Report, February 5, 1990, p. 74.

Creativity results in the production of novel or new ideas (Amabile, 1988). Creativity means doing things differently: being unique, clever, innovative, or original. Creative solutions are those that aren’t limited by self-imposed boundaries, those that consider the full spectrum of options from logical to seemingly illogical, and those that result in the creation of new and improved ways of doing things.

Critical thinking involves determining what we know and why we know it; creativity involves generating, considering, and using new ideas, concepts, and solutions. Applied together, the two strategies enable decision makers to analyze objectively and reason out the situation facing them and to come up with different and potentially unexpected ways of addressing and correcting problems.

This introduction provides some background information and offers an example of the rational decision process: the method generally believed to be used by decision makers and the method our education system teaches us to apply. However, rational decision making rarely occurs in the real world, at least for most of the complex, complicated, and unique problems facing business decision makers. To the extent we are able to meet the assumptions underlying the application of the rational process, our decisions approach optimality, but these ideal circumstances rarely (if ever) occur. Instead, we tend to shortcut the process and latch onto the first potential solution that meets our minimum expectations so we can move on to the next problem facing us in our busy lives.

Part I of this text lays the foundation for understanding the many internal factors that influence our decisions. As living beings, we have a host of biological, emotional, and psychological processes that (often without our knowledge) affect how we make decisions, and the chapters in this section analyze how these elements alter and distort our thinking ability. Part II focuses on understanding how we know what we know. The chapters in this section explore the elements of critical thinking: our attitude and belief infrastructure, which sets in motion our interpretation of what we hear, considering the source of information presented to us, weighing alternative explanations for what we are told, and testing the facts as we understand them. Part III deals with thinking creatively. In these chapters, a framework for creativity is offered, the stages of creativity are presented, and creativity-enhancing techniques are discussed.

Many of the decisions we make and the problems we face don’t require much in the way of critical thinking or creativity. Applying rational decision techniques or intuition can most likely solve our everyday routine, repetitive, and minor problems. Using rules of thumb or general guidelines can speed up the decision process, and the results are generally “good enough” for the current situation—thinking critically and solving problems creatively take time and effort, and we should apply these scarce resources where they are most needed. As decisions become more important and problems become more difficult, the energy required by critical thinking skills and creative problem solving can improve the quality of our thought processes and increase the likelihood of uncovering optimal solutions.

If not all decisions require us to be critical in our thinking and creative in our problem solving, how are we to know when to apply these skills? To understand when the use of critical thinking skills and creative problem-solving techniques will be most beneficial, we need to know something about the type of decision to be made, and we need to understand how decisions should be made under perfect conditions. If we subjected every decision we made to what is known as the rational decision process, we would end up with the best, most optimal solution all the time. Of course, this would also mean that we would make very few decisions and that we would spend most of our time attempting to solve problems and very little time actually implementing solutions. Under ideal conditions (in other words, not in the real world), problem solving should model the following steps.

THE RATIONAL DECISION PROCESS

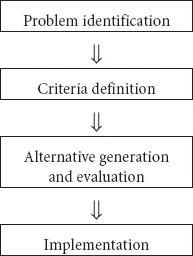

If decision makers had access to all the relevant information they needed, had enough time and energy to reach the best possible solution, and were unimpeded by “being human,” they would always use the rational decision process. All of us strive to make the best decisions we can, but we are usually limited by certain constraints. Sometimes, we don’t have enough information or enough time, or we just aren’t sure what we need to do to develop an optimal answer. We would like to make the most reasonable, logical, and objective decision possible, but we are seldom able to arrive at an optimal solution. Most of the time, to the extent possible, we try to be as rational as we can by using what economists term the rational decision-making process, a problem-solving approach that involves the following sequence of events: problem identification, criteria definition, alternative generation and evaluation, and implementation (see Figure 1.1).

Problem identification. To come up with a rational solution, decision makers must first recognize that a problem exists. This sounds obvious, but research has demonstrated that problem definition is not as straightforward as it would seem. Is a 5% sales decrease a problem? What about a 2% decline? Is a 20% increase a problem if our company has limited production capacity? Rarely are the situations we confront clearly labeled as problem or nonproblem. In addition, people can distort, ignore, omit, and discount information to such an extent that they often deny they are faced with a problem (Cowan, 1986). Managers with a morale problem in their department may convince themselves that the situation isn’t quite as bad as some believe, or even that the symptoms they witness are related to something else entirely and no problem exists. Cultural factors have also been found to influence the extent to which individuals perceive a situation as a problem. For example, an American manager might define a notice from a prime supplier that necessary construction materials will be 3 months late as a problem, whereas a more situation-accepting Asian manager might not call the identical situation a problem because Asian cultures are more likely to believe that the outcome is simply fate or God’s will (Adler, 1997).

Figure 1.1. The Rational Decision Process

Criteria definition. Most problems are multidimensional, and decision makers must determine what factors should be considered to resolve the problem they are facing. Perfectly rational decision makers would identify all the relevant criteria that might influence the decision process. The range of possible objectives for a specific problem might include price, quality, features, dependability, reputation, and so on. If certain criteria are not identified as relevant, then they have no impact on the subsequent decision process. Once the important criteria are found, the decision maker needs to recognize that not all of the factors are equally important to problem resolution. For example, people are often willing to sacrifice higher quality to gain a lower price. A difficulty many problem solvers face is that they fail to take into account an important criterion when considering their options, or they allow irrelevant criteria to influence their judgment. Although we might initially think service availability is unimportant when we make our decision to purchase office computers, we may later discover that on-site maintenance is critical after an employee experiences a computer breakdown. Or we may have identified all the important decision criteria correctly, but then we allow irrelevant factors such as persuasive sales pressure or emotiona...