![]()

CHAPTER 1

Major Aims of This Book

David P. Farrington &

Rolf Loeber The main aim of this book is to review knowledge about serious and/or violent juvenile (SVJ) offenders. These are a group of offenders who pose a great challenge to juvenile justice policy, and who are responsible for a disproportionate fraction of all crime. Given population trends, the number of teens in the 14 to 17 age group is anticipated to increase by 20%. If the rate of teen homicide and violence remains at current levels, this will mean a substantial increase shortly in the volume of juvenile violence at the beginning of the next century (Fox, 1996).

This book, the main report of the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) Study Group on Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders, addresses serious and violent juvenile delinquency. The volume aims to integrate knowledge about risk and protective factors and about the development of juvenile offending careers with knowledge about prevention and intervention programs, including interventions in the juvenile justice system, so that conclusions from one area can inform the other. Much of our knowledge about risk/protective factors and prevention/intervention programs does not apply specifically to SVJ offenders, so the Study Group commissioned specific new analyses that are included in various chapters.

There have been several recent major reports on violence: from the National Academy of Sciences Panel on Violence (Reiss & Roth, 1993), the American Psychological Association Commission on Violence and Youth (Eron, Gentry, & Schlegel, 1994), Harvard Law School (Ethiel, 1996), the Council on Crime in America (Bell & Bennett, 1996), and the University of Maryland Report to the U.S. Congress (Sherman et al., 1997). All of these reports are extremely valuable. Some of the reports cover topics that this volume does not attempt to cover: biobehavioral influences on violence, for example, in the National Academy of Sciences volume (Reiss, Miczek, & Roth, 1994), and the influence of labor markets and places in the University of Maryland Report to the U.S. Congress (Sherman et al., 1997). Also, the present volume does not claim to address larger societal and structural influences on violence (e.g., welfare legislation) or female violence, because of the relative paucity of studies. None of the above studies, however, covers the same ground as this volume, which systematically links risk and protective factors of violence to a wide range of interventions, ranging from early childhood to adulthood, from preventive approaches to aftercare approaches for known violent youth, and from approaches in the home and school to approaches in the juvenile justice system. Thus, the main aim of the present volume is to be more comprehensive in some ways than past works, but also more selective by focusing on serious and violent offenders. As a result, the present volume, by means of the results of expert reviews and newly commissioned meta-analyses, points to many options for advancing knowledge and improving interventions.

The main focus of this book is on serious violent and serious nonviolent juvenile offenders. Serious violent offenses include homicide, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, and kidnapping. Serious nonviolent offenses include burglary, motor vehicle theft, theft over $100, arson, drug trafficking, and extortion (see Chapter 2 for more details of these definitions). This book aims to establish the overlap between serious violent juvenile offenders and serious nonviolent juvenile offenders.

The Study Group initially intended to focus on serious and/or violent and/or chronic juvenile offenders. Unfortunately, it proved difficult to find a satisfactory definition of chronic (frequent and/or persistent) offending that was equally applicable to court referrals, arrests, and self-reported offending. For example, a criterion of committing three or more serious violent offenses as a juvenile would identify hardly any chronic offenders in court records (Snyder, this volume) but a large number in self-reports (Elliott, 1994). Nevertheless, although chronic offenders are not one of the major concerns of this book, efforts will be made to establish the overlap between SVJ offenders and chronic offenders (defined in various ways), especially in the Appendix by Snyder. Similarly, efforts will be made to specify what proportion of serious violent and serious nonviolent offenses are committed by chronic offenders (defined in various ways).

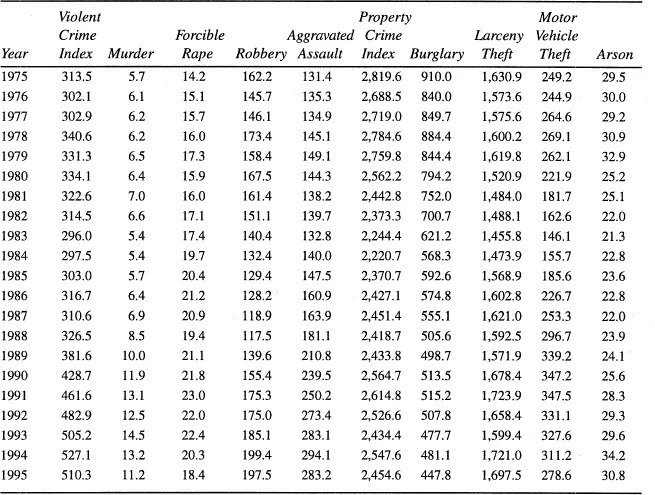

Snyder, Sickmund, and Poe-Yamagata (1996) and Snyder and Sickmund (1995) have summarized recent trends in juvenile arrest rates for index offenses. Table 1.1 shows the numbers in detail. Arrests for index violence offenses increased by a remarkable 61% between 1988 and 1994, but arrests for index property offenses stayed virtually constant, increasing by only 5% over the same time period. The juvenile arrest rate for homicide increased by 90% between 1987 and 1991 but has since remained tolerably constant. The juvenile arrest rate for robbery increased by 70% between 1988 and 1994, and the aggravated assault rate increased by a similar 62%. The forcible rape rate has stayed tolerably constant over this time period.

TABLE 1.1 Juvenile Arrest Rates in the United States: 1975-1995 (arrests of 10- to 17-year-olds/100,000 10- to 17-year-olds)

SOURCE: Arrest rates were developed by Howard Snyder at the National Center for Juvenile Justice in 1997 using (a) unpublished, machine-readable, 1975-1995 arrest counts and the arrest sample’s total population statistics from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program, and (b) machine-readable data files of 1975-1995 estimates of the resident population of the United States in single years of age from the U.S. Bureau of the Census.

Similar increases in violence are generally not seen in the Monitoring the Future study, which is the major repeated self-report survey based on national samples (of high school students). For example, the percentage of boys who said that they had “hurt someone badly enough to need bandages or a doctor” in the previous year was 20.1% in 1987 and 20.4% in 1995. However, there was an increase in the small proportion who had done this three or more times (from 2.8% to 6.1%). The percentage of boys who said that they had “used a knife or gun or some other thing (like a club) to get something from a person” was 5.1% in 1987 and 5.4% in 1995 (Maguire & Pastore, 1996, Table 3.48).

OJJDP’s Comprehensive Strategy

The work of the Study Group was inspired by OJJDP’s Comprehensive Strategy for Serious, Violent, and Chronic Juvenile Offenders (Howell, this volume; Wilson & Howell, 1993). This is based on five general principles:

- Strengthen the family in its primary responsibility to instill moral values and provide guidance and support to children.

- Support core social institutions (schools, religious institutions, and community organizations) in their roles of developing capable, mature, and responsible youth.

- Promote delinquency prevention as the most cost-effective approach to dealing with juvenile delinquency. When children engage in “acting out” behavior, such as status offenses, the family and community, in concert with child welfare services, must take primary responsibility for responding with appropriate treatment and support services. Communities must take the lead in designing and building comprehensive prevention approaches that address known risk factors and target youth at risk of delinquency.

- Intervene immediately and effectively when delinquent behavior occurs, to prevent delinquent offenders from becoming chronic offenders or progressively committing more serious and violent crimes. Initial intervention attempts should be centered on the family and other core social institutions.

- Identify and control the small group of serious, violent, and chronic juvenile offenders who have failed to respond to intervention and nonsecure community-based treatment and rehabilitation services offered by the juvenile justice system.

The Comprehensive Strategy recommends prevention efforts targeting five categories of risk factors:

- Individual characteristics such as alienation, rebelliousness, and weak bonding to society

- Family influences such as parental conflict, child abuse, and a family history of problem behavior (criminality, substance abuse, teen pregnancy, school dropout)

- School experiences such as early academic failure and lack of commitment to school

- Peer group influences such as friends who engage in problem behavior (including gangs and violence)

- Neighborhood and community factors such as economic deprivation, high rates of substance abuse and crime, and low neighborhood attachment

The Comprehensive Strategy recommends that communities should identify and understand to what risk factors their children are exposed and should implement prevention programs designed to counteract these risk factors. Communities should also aim to enhance protective factors that promote desirable behavior, health, well-being, and personal success. Recommended prevention programs targeting the five categories of risk factors include the following:

- Youth service programs, adventure training, mentoring, literacy programs, Head Start, recreational programs

- Teen pregnancy prevention, parental skills training, family crisis intervention services, family life education for teens and parents

- Drug and alcohol prevention and education, bullying prevention, violence prevention, alternative schools, truancy reduction, law-related education, afterschool programs for latchkey children

- Gang prevention and intervention, peer counseling and tutoring, community volunteer service

- Community policing, Neighborhood Watch, neighborhood mobilization for community safety, foster grandparents

The Comprehensive Strategy aims to improve the juvenile justice system response to delinquent offenders through a system of graduated sanctions and a continuum of treatment alternatives that include immediate intervention, intermediate sanctions, community-based corrections sanctions including restitution and community service, and secure corrections including community confinement and incarceration in training schools, camps, and ranches.

Graduated-sanctions programs should use risk and needs assessments to determine the appropriate placement for the offender. Risk assessments should be based on the seriousness of the delinquent act, the potential risk for reoffending, and the risk to public safety. Needs assessments will help ensure that different types of problems are taken into account when formulating a case plan, that a baseline for monitoring a juvenile’s progress is established, that periodic reassessments of treatment effectiveness are conducted, and that a systemwide database of treatment needs can be used for the planning and evaluation of programs, policies, and procedures. Together, risk and needs assessments will help to allocate scarce resources more efficiently and effectively.

Aims of the Study Group and This Book

OJJDP’s Comprehensive Strategy, the guide to its implementation (Howell, 1995), and the sourcebook (Howell, Krisberg, Hawkins, & Wilson, 1995) provide an excellent framework for understanding, preventing, and controlling serious and/or violent juvenile (SVJ) offending. However, there is a need for more detailed quantitative analyses of risk and protective factors for SVJ offending; most previous reviews focus on delinquency in general rather than on SVJ offenders. Similarly, there is a need for more detailed quantitative analyses of the effectiveness (and cost-effectiveness) of prevention and intervention programs, again focusing on their effects on SVJ offenders.

This book aims to provide reviews of risk and protective factors and prevention and intervention programs focusing especially on SVJ offenders. It also aims to integrate the two different areas, so that knowledge about risk and protective factors is linked to knowledge about prevention and intervention programs, and vice versa. Ideally, prevention/intervention programs should be based on research on risk/protective factors, and conversely, conclusions about causal effects of risk/protective factors might be drawn from knowledge about the effectiveness of prevention/intervention programs. Attempts will be made to compare SVJ offenders with other offenders as we...