The SAGE Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences

- 528 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The SAGE Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences

About this book

Click ?Additional Materials? for downloadable samples

"The 24 chapters in this Handbook span a wide range of topics, presenting the latest quantitative developments in scaling theory, measurement, categorical data analysis, multilevel models, latent variable models, and foundational issues. Each chapter reviews the historical context for the topic and then describes current work, including illustrative examples where appropriate. The level of presentation throughout the book is detailed enough to convey genuine understanding without overwhelming the reader with technical material. Ample references are given for readers who wish to pursue topics in more detail. The book will appeal to both researchers who wish to update their knowledge of specific quantitative methods, and students who wish to have an integrated survey of state-of- the-art quantitative methods."

—Roger E. Millsap, Arizona State University

"This handbook discusses important methodological tools and topics in quantitative methodology in easy to understand language. It is an exhaustive review of past and recent advances in each topic combined with a detailed discussion of examples and graphical illustrations. It will be an essential reference for social science researchers as an introduction to methods and quantitative concepts of great use."

—Irini Moustaki, London School of Economics, U.K.

"David Kaplan and SAGE Publications are to be congratulated on the development of a new handbook on quantitative methods for the social sciences. The Handbook is more than a set of methodologies, it is a journey. This methodological journey allows the reader to experience scaling, tests and measurement, and statistical methodologies applied to categorical, multilevel, and latent variables. The journey concludes with a number of philosophical issues of interest to researchers in the social sciences. The new Handbook is a must purchase."

—Neil H. Timm, University of Pittsburgh

The SAGE Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences is the definitive reference for teachers, students, and researchers of quantitative methods in the social sciences, as it provides a comprehensive overview of the major techniques used in the field. The contributors, top methodologists and researchers, have written about their areas of expertise in ways that convey the utility of their respective techniques, but, where appropriate, they also offer a fair critique of these techniques. Relevance to real-world problems in the social sciences is an essential ingredient of each chapter and makes this an invaluable resource.

The handbook is divided into six sections:

• Scaling

• Testing and Measurement

• Models for Categorical Data

• Models for Multilevel Data

• Models for Latent Variables

• Foundational Issues

These sections, comprising twenty-four chapters, address topics in scaling and measurement, advances in statistical modeling methodologies, and broad philosophical themes and foundational issues that transcend many of the quantitative methodologies covered in the book.

The Handbook is indispensable to the teaching, study, and research of quantitative methods and will enable readers to develop a level of understanding of statistical techniques commensurate with the most recent, state-of-the-art, theoretical developments in the field. It provides the foundations for quantitative research, with cutting-edge insights on the effectiveness of each method, depending on the data and distinct research situation.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Section VI

FOUNDATIONAL ISSUES

Chapter 20

PROBABILISTIC MODELING WITH BAYESIAN NETWORKS

20.1. INTRODUCTION

20.2. PHILOSOPHICAL BACKGROUND

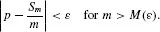

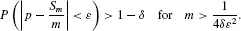

20.2.1. The Relative Frequency Approach to Probability

20.2.1.1. Relative Frequencies

20.2.1.2. Sampling

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- SECTION I SCALING

- SECTION II TESTING AND MEASUREMENT

- SECTION III MODELS FOR CATEGORICAL DATA

- SECTION IV MODELS FOR MULTILEVEL DATA

- SECTION V MODELS FOR LATENT VARIABLES

- SECTION VI FOUNDATIONAL ISSUES

- Name Index

- Subject Index

- About the Editor

- About the Contributors