![]()

A

Adjectives

Adjectives are words that denote properties of objects, such as size (big), shape (round), color (red), texture (rough), material (wooden), state (sleeping), and aesthetic qualities (beautiful), among many others. As a grammatical category in English, adjectives modify nouns, appearing in either a prenominal position (before the noun, such as What an adorable baby!) or in predicative position, often after a copular verb (as in, Your baby is adorable!). Their surface-level distribution is linked to their position in the syntactic structure and their semantic representation, and therefore distinguishes them from quantificational terms, such as some and every, and number words, such as two, which have a partially overlapping distribution. Adjectives are among the first words produced by young children. Moreover, a range of adjectives appears frequently in child-directed speech, providing children with information about semantic differences within the category of adjectives.

For example, gradable adjectives such as big are likely to appear in comparative constructions (X is bigger than Y) and are modified by adverbs such as very, indicating that size depends on a standard of comparison. Although number words and quantifiers also appear prenominally, neither can appear with the comparative morpheme –er or be preceded by the intensifier very. By contrast, these words can appear in partitive constructions (X of the Y), whereas adjectives cannot. Kristen Syrett and colleagues have shown that preschoolers are able recruit these distributional characteristics when learning new words. Even some gradable adjectives differ with respect to the adverbs allowed to modify them as well as inferences based on their appearance in a comparative construction. For example, while it is acceptable to say that something is completely full or clean, it is not permissible to describe something as completely tall or big. Saying that x is fuller or bigger than y does not entail that either x or y is full or big, but saying that x is bumpier or dirtier than y requires x to be bumpy or dirty and may presuppose that y is as well. Work by Kristen Syrett and Jeffrey Lidz shows that 2-year-olds are aware of restrictions on adverbial modification and can recruit this information when classifying novel adjectives.

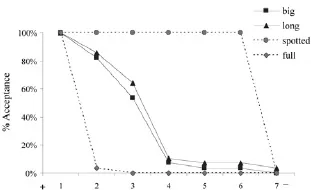

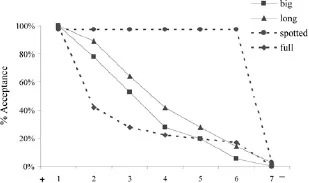

Gradable adjectives come in multiple varieties. Kristen Syrett, Christopher Kennedy, and Jeffrey Lidz have demonstrated that 3- to 5-year-olds (like adults) differentiate among these adjectives with respect to the role of the context in setting the standard of comparison. With adjectives like big, children readily shift the standard of comparison with the context, while they do not with full or spotted. For example, no matter how big or long two items are, as long as the size of one exceeds the other, it is the big or long one; that’s not so with full or spotted. Likewise, the cutoff for what counts as big or long in a series of objects is approximately the midpoint, whereas what counts as full or spotted depends on whether or not the maximal or minimal standard has been met, respectively. (See Figures 1 and 2.) Other work has shown that preschoolers take into account real-world knowledge, the range of comparison, and object kind when setting the standards. Susan Gelman and Karen Ebeling have also shown that preschoolers can move between different types of standards, for example, a normative standard (what counts as big for objects of a particular kind), a perceptual standard (what counts as big in the context at hand), and a functional standard (what is too big for the present purposes).

Preschoolers also appear to be aware that the syntactic position of an adjective and its prosodic prominence can carry implications about the speaker’s intentions. For example, the daxy one is likely to be interpreted as a contrast between an object that is daxy and another object of the same kind that is not daxy, while the one that is daxy is likely to be interpreted as picking out an object that simply has the property of being daxy. By age 5, children are not only aware of these contrasts but treat gradable adjectives like big differently from color terms. A request for a BIG dax is more likely to launch a search for a within-kind contrast object than a request for a YELLOW dax or a dax that is yellow or big. This finding is consistent with the input children receive. Although color terms can be gradable, they are typically not treated as such in child-directed speech. Parents are likely to ask their children, “What color is this?” but instead, “Where or which is the big one?” or “Which one is bigger?” Many children take years to master color terms but, in the interim, seem to be aware of which adjectives refer to color, often supplying an incorrect color term in response to a question about color.

When children learn a new adjective, they need to know whether to extend the label and corresponding property to a new referent. Taxonomic level—that is, what kind of conceptual category something belongs to—plays an important role. A series of experiments by Sandra Waxman and her colleagues has shown that when 3-year-olds are shown a spotted green elephant labeled by a novel adjective such as blickish contrasted with another elephant that is solid green and described as not blickish, they are likely to interpret the adjective as spotted. They do not do so when shown a contrasting object from another basic-level category (such as solid green rabbit) or when the adjective is not present. However, when shown objects from across basic-level categories that share the same property and that are labeled with a common adjective, 3-year-olds willingly extend the property to yet another basic-level category. The adjective seems to serve as an invitation for the child to perform a comparison and notice commonalities among category members. Such comparisons are most effective when children are shown multiple exemplars and when presented with familiar objects.

Within the grammatical category of adjectives, there are those that express stage-level properties (like thirsty) and those that express more stable traits or individual-level properties (like friendly or gentle). Across experiments, children routinely confer a privileged status to the basic-level category (for example, dog) and subordinate level (beagle) rather than to the superordinate-level category (animal). For example, when shown an animal labeled with one of these adjectives, 4-year-olds are willing to extend the property to another animal when the property is a stable trait and when the animal is a member of the same basic-level category.

Figure 1 Adults

Figure 2 Children

Yes/no judgments reported in Syrett et al. (2006), rendered by adults (Figure 1) and children (Figure 2), along a 7-point scale of objects ranging from high to low degree of the property indicated to the right. Participants saw cubes (big), rods (long), disks ranging from very spotted to one with no spots (spotted), and small containers ranging from full to empty (full).

There are a number of challenges facing the young word learner acquiring adjectives. Children must recruit real-world knowledge to know whether the adjective–noun combination yields a true statement. They must also learn the ordering between adjectives and nouns in their language. To become efficient language processors, they need to recognize that it may not be necessary to hold off assigning interpretation until they hear the modified noun. They must learn that many adjectives are linked to a contrasting antonym in their polarity (big/small). Finally, they must learn that, in languages such as Spanish or French, morphosyntax requires that the determiner, noun, and adjective all agree in gender (une robe bleue, “a blue dress”), that the noun may be dropped (el rojo, “the red one”), and that different interpretations arise from the verb combining with the adjective (estar v. ser alto, to be “high up” v. “tall”). Despite the fact that it may take children years to incorporate these linguistic constraints, many adult-like semantic features of adjectives appear to be in place by age 5, perhaps even earlier.

Kristen Syrett

Rutgers University

See Also: Child-Directed Speech (Features of); Color Cognition and Language Development; Early Word Learning; Grammatical Categories; Quantifiers; Semantic Development; Syntactic Bootstrapping; Word Learning Strategies.

Further Readings

Ebeling, K. S. and S. A. Gelman. “Children’s Use of Context in Interpreting Big and Little.” Child Development, v.65 (1994).

Graham, S., C. Cameron, and A. Welder. “Preschoolers’ Extension of Familiar Adjectives.” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, v.91 (2005).

Nadig, A., J. Sedivy, A. Joshi, and H. Bortfeld. “The Development of Discourse Constraints on the Interpretation of Adjectives.” In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development, B. Beachley, A. Brown, and F. Conlin, eds. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press, 2003.

Smith, L. B., N. Cooney, and C. McCord. “What Is High? The Development of Reference Points for High and Low.” Child Development, v.57 (1986).

Syrett, K., E. Bradley, C. Kennedy, and J. Lidz. “Shifting Standards: Children’s Understanding of Gradable Adjectives.” In Proceedings of the Inaugural Conference on Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition: North America, Honolulu, HI, Vol. 2, K. Ud Deen, J. Nomura, B. Schulz, and B. D. Schwartz, eds. University of Connecticut Occasional Papers in Linguistics, v.4 (2006).

Syrett, K., C. Kennedy, and J. Lidz. “Meaning and Context in Children’s Understanding of Gradable Adjectives.” Journal of Semantics, v.27 (2010).

Syrett, K. and J. Lidz. “30-Month-Olds Use the Distribution and Meaning of Adverbs to Interpret Novel Adjectives.” Language Learning and Development, v.6 (2010).

Syrett, K., J. Musolino, and R. Gelman. “How Can Syntax Support Number Word Acquisition?” Language Learning and Development, v.8 (2012).

Waxman, S. R. and R. S. Klibanoff. “The Role of Comparison in the Extension of Novel Adjectives.” Developmental Psychology, v.36 (2000).

Adolescent Language Development and Use

Many years ago, it was widely believed that language development was virtually complete by the time a child reached 5 or 6 years of age and that further growth in language beyond those years consisted mainly of refinements in the use of grammar and the addition of school-related vocabulary words. In the 1970s, however, researchers in the United States began publishing studies of language development in older children and adolescents, reporting that substantial growth occurred well beyond the preschool years in areas such as the use of complex syntax in spoken and written language.

Since those early days, researchers from around the world have continued to study later language development with intensity, reporting that substantial changes occur not only in syntax and vocabulary but also in the areas of figurative language, verbal reasoning, and pragmatics—the social use of language. This article will highlight some of the key aspects of spoken and written language that develop during adolescence, encompassing the years between 12 and 18. It should be noted that changes that occur during these years are gradual, and that growth is most apparent when individuals from widely separated age groups (e.g., 12 versus 15 years) are compared in research studies. It should also be noted that an adolescent’s performance on measures of later language development is impacted by a variety of external factors, including educational opportunities, socioeconomic status, and family influences, and that teens whose schools, neighborhoods, and parents support academic achievement are likely to demonstrate more advanced spoken and written language skills than their less fortunate peers. It also must be mentioned that growth in language in all areas continues beyond adolescence and into adulthood.

Syntax

Adolescence is sometimes viewed as a stage in human development when communication is marked by a predominance of sarcasm and single-word utterances, particularly in response to adults’ questions. Although simplified communication does occur in adolescents, typically, developing teens also demonstrate a remarkable ability to express themselves in ways that are complex yet clear, precise, and efficient. The secret to revealing this hidden linguistic competence is to engage adolescents in tasks that call upon their knowledge and enthusiasm for topics studied in school or encountered beyond the classroom during free-time activities. For example, when adolescents are prompted to speak or write in the narrative, expository, or persuasive genres, they are likely to use sentences that are longer and contain a greater number of subordinate clauses than when they are engaging in typical conversations. For example, the following passage was produced by a 17-year-old girl during a narrative writing task:

As I was walking down the street with my friend Sadie, we came upon a house that has always been rumored to be haunted.

It was quite large and looked to have once been painted bright colors.

But years of neglect and disuse had turned it a brown color and left it peeling.

There were the usual trespassing signs posted.

But most everyone ignored those.

Adding to the home’s mystique was the fact that none of the neighboring houses had been able to keep their occupants for very long.

The syntactic complexity of this passage is far greater than what one might expect to find in the narrative writing of a typical 10-year-old child or even in the daily conversational speech of the same adolescent girl. The first sentence, for example, which is 24 words long, contains one main clause and three different types of subordinate clauses (adverbial, relative, and infinitive) embedded within it. The sentence also employs both active and passive voice constructions. The final sentence also contains four types of clauses (one main and three subordinate) and is 24 words long. Furthermore, just in this short passage, the author has employed some rather sophisticated vocabulary words. These include a metalinguistic (rumored) and a metacognitive (ignored) verb, five abstract nouns (neglect, disuse, mystique, fact, occupants), and four derived adjectives (haunted, trespassing, posted, neighboring), illustrating the overlap between later syntactic and lexical development, a phenomenon known as the syntax-lexicon interface.

A similar level of syntactic complexity can be seen in the following passage of expository discourse produced by a 15-year-old boy who was asked to describe the goal of chess:

When you are playing chess, you are trying to capture your opponent’s pieces.

And often a way to do this is to gradually push them back across the board with an advancing wall of pawns or other pieces, to sort of trap them into a smaller space and to gradually pick off all the outlying pieces until eventually the king is trapped.

The second sentence, which is 49 words long, reflects a sophisticated level of knowledge of the game of chess. And yet, despite its length, the sentence expresses the speaker’s knowledge in a way that is clear, precise, and efficient through the use of one main clause, five subordinate clauses, and an apt selection of literate words and phrases (e.g., advancing wall of pawns).

A high level of syntactic complexity can also be observed when adolescents are engaged in persuasive discourse tasks, as in the following excerpt from a 16-year-old girl who was writing about the controversial topic of training animals to perform in circuses:

I believe animals should only be trained and put in a circus if they have no possible way of living a life of their own in the wild.

If an elephant is born and its mother dies and the baby gets hurt and then someone brings it in, then that animal could be trained.

Even though people may lose their jobs, we as a world are losing our wild animals.

We can’t spare animals just to train them for our entertainment.

I think it is wrong to have these animals in the circus. Humans can find other ways of amusing themselves.

The first two sentences of this passage are particularly dense with information. In the first sentence, which contains 28 words, the author expresses her views in a forthright manner through the use of one main clause and four subordinate clauses. The second sentence with its 26 words is syntactically even more com...