![]()

1

We Know What to Do, So Why Do We Fail?

The problem is not that we do not know enough—it is that we do not do what we already know.

—Schmoker (2005, p. 148)

At seven in the morning, school district superintendents, directors of instruction, professors of educational leadership, and other educational leaders have gathered on the campus of San Diego State University (SDSU) in San Diego, California. The purpose for the meeting is to brainstorm ways that the Educational Leadership Department at SDSU can assist school districts in their efforts to improve student learning. The room is buzzing with friendly exchanges.

A weary-eyed professor at the far end of the table offers a conversation starter: “Much research points to the promise of increased student learning when school leaders and teachers work together as a professional learning community, sharing the vision and collaborating for such important functions as data analysis, lesson study, and curriculum alignment.”

At this point, one noticeably uncomfortable younger superintendent asks pointedly, “Well, if we know what needs to be done to get good results, why can’t we do it?” Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert Sutton (2000), in their study of successful private sector companies, described this divide between knowing what needs to be done and doing it as one of the “great mysteries in organizational management: why knowledge of what needs to be done frequently fails to result in action or behavior consistent with that knowledge” (p. 4).

Responses to the superintendent’s question from the school leaders in the room immediately focus on the usual barriers to success: the changing student population, inadequate teacher preparation, English language learner difficulties, lack of parent involvement, bureaucratic requirements, union stalemates, insufficient fiscal resources, and unreasonable pressures of the No Child Left Behind Act.

Most in the group nod their heads in agreement with one superintendent who interjects, “But there are schools out there where student achievement is improving in spite of the barriers we are all talking about.” He asks pointedly, “How are they able to get past those barriers?”

THE “GOOD TO GREAT” RESEARCH PROJECT

This pivotal question prompted us to seriously rethink just how some schools are able to succeed in the face of seemingly impossible barriers. The research of Jim Collins, reported in his bestselling book Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap … and Others Don’t (2001), led us to look to the school leader for answers to the puzzle. Collins was asking the same question we are asking—but he was asking the question in the corporate world. His research team of 21 graduate students from the University of Colorado Graduate School of Business spent five years exploring this question. Their research zeroed in on how good companies become great companies, and how they then stay that way. The great companies of the Collins’ study faced all the same constraints of similar companies, yet made gains and sustained those gains, while the other companies made few or no gains, and were unable to sustain any gains they did make. The researchers found that the key to these companies’ success was their CEOs. They also found that the CEOs of the successful companies exhibited certain specific powerful characteristics and behaviors. Moreover, these characteristics and behaviors were absent in the leaders of the less-successful companies in the study.

As faculty in the Educational Leadership Department at SDSU, we realized that the results of Collins’ research about private sector leadership might hold pieces to the puzzle about what constitutes effective school leadership and why some schools blossom and others don’t.

At the time, our interest in successful school leadership was being put to a practical test at SDSU, where we were working to redesign educational administration preparation programs to better prepare principals for twenty-first-century school leadership. Suppose our preparation programs were missing the point?

Collins and his research team addressed precisely the question we wanted to explore in public school leadership. In their study, successful leaders were identified by exploring the characteristics of good companies that transitioned to great companies. Eleven companies were studied that made the leap from good results to great results, and then sustained those results. To select these companies, financial analysis was necessary to find companies that showed a pattern of “good” performance punctuated by a transition point, after which these companies shifted to “great” performance. Naturally, the profit-oriented business performance was defined in terms of corporate profit.

The Level 5 Executive

The study looked at what the great companies had in common that distinguished them from a group of similar comparison companies. Factors were found that were common to all great companies but that did not always exist among the comparison companies. A central element of the research findings was the presence of what Collins (2001) termed a “Level 5 Executive” (p. 20). The Level 5 Executive is at the top of a five-level hierarchy of leadership ability that Collins and his research team developed when they identified shared capabilities of the CEOs of all of the Good to Great companies in their research.

We were fascinated to learn that Collins’ researchers were not specifically looking for leadership as a necessary ingredient for company success. Nevertheless, the information supporting the distinct role of specific leadership characteristics was overwhelming and convincing. Collins’ research team debated extensively how to describe the most effective leaders and finally settled on the label “Level 5 Executive” to avoid making them sound weak or meek. These executives did not necessarily move in sequence from Level 1 to Level 5, but the evolution of the Level 5 Executive is cumulative, with these executives embodying the characteristics of all five levels of the hierarchy. Level 5 Executives build enduring greatness through a paradoxical blend of personal humility and professional will.

The insights into leadership found by the Collins study were both surprising and, in some cases, contrary to conventional wisdom. They suggest a different paradigm for leadership training—one that we suspect has implications for producing successful school leaders.

The Level 5 School Executive

Thus, we set out to determine whether the Collins (2001) research could apply to school leaders. Are there identifiable characteristics of successful school principals that can be correlated with long-term educational success? Could the absence of the leadership characteristics Collins found in his study be the reason many school leaders fail to accomplish what they set out to accomplish? Can the characteristics of great executives be taught and learned as part of an administrator preparation program?

To answer these questions, we studied great school principals using a semistructured qualitative interview technique. We replicated the interview questions in Collins’ research of successful private sector companies with modifications for public school leadership, then we interviewed a group of principals whose schools moved from good to great in student achievement and stayed there over a period of time. In keeping with Collins’ research protocol, we also studied principals selected as a comparison group. The schools of these comparison principals were good, but did not move to great and stay there. The purpose of our interviews was to examine the leadership characteristics and behaviors of highly successful principals and the comparison principals as reflected in their responses. (Note: The protocol used in our study for selection of participants and interview questions may be found in Resources A, B, and C.)

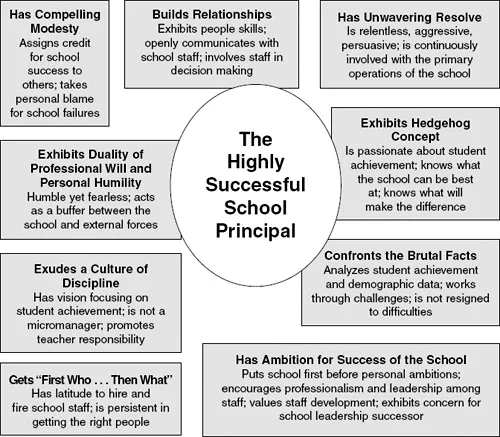

The Ability to Build Relationships

We found that the principals of highly successful schools in our study exhibited the characteristics and behaviors of the Level 5 Executives of Collins’ research with one important difference: all of the highly successful principals also demonstrated a strong ability to build relationships among their faculty. The literature on successful schools, combined with our own research focusing on highly successful principals, has persuaded us that the one most critical piece of the successful school puzzle is the presence of a principal with the critical leadership attribute of building relationships. This quality, along with the characteristics of the Level 5 Executive in Collins’ research, make up our framework for the highly successful school principal as defined in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Framework for the Highly Successful Principal

LEADERSHIP CHARACTERISTICS OF LEVEL 5 EXECUTIVES

In Collins’ private sector research, every one of the great CEOs in the Good to Great companies exhibited certain significant characteristics identifying each of them as a Level 5 Executive.

Duality of Professional Will and Personal Humility

The first of these characteristics was what Collins (2001) termed a “duality of professional will and personal humility” (p. 22). While on the surface the great CEOs in the study seemed quiet and reserved, hidden within each of them was intensity, a dedication to making anything they touched the best it could possibly be. We found this same characteristic among our highly successful principals when we modified Collins’ definition of “personal humility.” In Chapter 3, we expand on the modification of this characteristic as it pertains to our principals—where it was present and where it was not.

Ambition for the Success of the Company

The second leadership characteristic was “ambition for the success of the company rather than for one’s own personal renown” (p. 25). Great private sector leaders want to see the company even more successful in the next generation and are comfortable with the idea that most people won’t even know about the efforts they took to ensure future success. Our star principals displayed ambition for the success of the school that rivals the ambition demonstrated by the successful CEOs of the Collins study. In Chapter 5, we demonstrate what we found among all of the highly successful principals, first through the story of energetic Ms. Aspiration, principal of Mission Elementary School. She was able to fuel her own ambition for the success of the school by nurturing the ambitions of each of the faculty to unite in their individual efforts to raise test scores.

Compelling Modesty

A third characteristic identified by Collins’ research was “compelling modesty” (p. 27). When things go well, leaders with this trait give credit to others; when things go badly, they accept the blame. During the interviews, the Good to Great leaders would talk about the company and the contributions of other executives but would deflect discussion about their own contributions. Prevalent among our highly successful principals was a modesty that on the surface seemed to contradict their ambitions for the success of their school. Mr. Unpretentious of Bay View Elementary, whom we will meet later in this book, serves as a good example of this modesty among our principals. Throughout his interview, he credited the teaching staff for all successes of the school and only when asked about something that was tried but failed did he bring attention to his own contributions—and then only to blame himself for the failure. Conversely, the comparison principals were quick to blame someone other than themselves for failures.

Unwavering Resolve to Do What Must Be Done

It is probably no surprise that the fourth characteristic identified by the researchers was “unwavering resolve” to do what must be done to make the organization successful (p. 30). Leaders with this trait typically are driven with an unshakable need to produce results and to do whatever it takes to make the company great. Ms. Persevere, tireless principal of Mountain High Elementary, is the highly successful principal in Chapter 6 we draw on to demonstrate the unwavering resolve of all of our principals. When teachers are quick to make excuses for not following through with a program or strategy, Ms. Persevere jumps in to do it for them so they have no excuses. Her unwavering resolve to do what needs to be done serves as a model for each of the members of the staff of Mountain High Elementary School.

LEADERSHIP BEHAVIORS OF LEVEL 5 EXECUTIVES

The success of the CEOs of the Good to Great companies is not attributed solely to the presence of the key leadership characteristics we have just described. Kirkpatrick and Locke (1991) found that characteristics by themselves tell only part of the story, since there is much more to being an effective leader than the possession of certain characteristics.

Recent research, using a variety of methods, has made it clear that successful leaders are not like other people. The evidence indicates that there are certain core traits, which contribute to business leaders’ success. … Leaders do not have to be great men or women by being intellectual geniuses or omniscient prophets to succeed, but they do need to have the “right stuff” and this stuff is not equally present in all people. (pp. 49, 59)

Collins’ work expands on the idea of core leadership characteristics working in tandem with leadership behavior. He found a mutual interdependence between the personal characteristics and behaviors of his Level 5 Executive and the remaining findings of his research on companies that transitioned from being good companies to being great companies and sustained this greatness over time. Important leadership behaviors were present in all of the great CEOs; when combi...