![]()

1

Organizing Workplace Relationships

Mark arrived at the office at 8:00 a.m. and immediately went to the kitchen to get a cup of coffee. Janet was also getting a cup of coffee, so the two of them discussed the meeting scheduled for later that afternoon and how they felt about the proposal on the meeting’s agenda regarding expense reimbursement procedures. Both agreed that the new process would be really time-consuming and planned to argue against it. Tim walked in the kitchen just as Mark and Janet were finishing their conversation. Mark quickly left the room—he and Tim had had a pretty big argument a few days earlier, and Mark felt uncomfortable around Tim ever since. Mark then went to his office and looked at his calendar for the day. First up was a meeting with two other salespeople, Jenny and Pete, to discuss ideas about how to pitch the company’s latest product. He was looking forward to this meeting and hoping they could come up with some creative ideas. After that, Mark would meet with his supervisor for his semiannual performance evaluation. He was hoping for no surprises in that meeting. Then lunch with a new client, so he had to make sure he wasn’t late. He wanted to make sure that relationship got off on the right foot. That was just the first half of a typically busy day of work for Mark.

Consider Mark’s morning and the typical daily activities in a typical organization, including directing, collaborating, information gathering, information sharing, rewarding, punishing, conflict, resolution of conflict, controlling, feedback, persuasion, presenting, interviewing, reporting, gossiping, debating, supporting, selling, buying, ordering, managing, leading, and following. All of these activities occur in the context of interpersonal relationships. In fact, virtually all organizational activities occur in the context of relationships, even in “virtual” organizations among “virtual” coworkers who operate in different physical locales. Relationships are the essence of living systems and the basis of organization (Wheatley, 1994, 2001). It is through relationships that systems maintain balance (Katz & Kahn, 1978), chaos becomes order, and fragmentation is made whole (Wheatley, 2001). Accordingly, as Wheatley (2001) noted, scholars should focus attention on “how a workplace organizes its relationships; not its tasks, functions, and hierarchies, but the patterns of relationships and the capacities available to form them” (p. 39).

Relationships in the workplace are particularly important and consequential interpersonal relationships. An individual with a full-time job, for example, is likely to spend as much, if not more, of his or her time interacting with coworkers than with friends and family. Even when we’re not at work, we spend much of our time talking and thinking about work. We are largely defined by what we do for a living and with whom we work. Not surprisingly then, in many ways, our workplace relationships define who we are (Sluss & Ashforth, 2007).

In contrast to “acquaintances” or people who have limited contact with one another, an interpersonal relationship is characterized by repeated, patterned interaction over time (Sias, Krone, & Jablin, 2002). Unlike acquaintanceships, relationships are enduring, although some endure longer than others. Interpersonal relationships are also characterized by a feeling of connection beyond that experienced in an acquaintanceship. Again, relationships vary in the extent of this connection, but generally speaking, the closer the relationship, the stronger and more emotional the connection.

The term workplace relationship generally refers to all interpersonal relationships in which individuals engage as they perform their jobs, including supervisor–subordinate relationships, peer coworker relationships, workplace friendships, romantic relationships, and customer relationships. These relationships have been studied by a variety of scholars in a variety of disciplines. As a result, we know a great deal about workplace relationships and their role in organizational processes and individuals’ lives.

Our study of workplace relationships has been limited, however. As the following chapters will demonstrate, the bulk of research on workplace relationships has been guided by a postpositivist perspective that conceptualizes workplace relationships in a specific way and centers on identifying relationships among variables with the goal of predicting effectiveness in specific contexts. Certainly this work is of great value, providing an enormous amount of knowledge about workplace relationships and their roles in organizational processes.

Relying on a single theoretical lens and conceptualization of a subject narrows our vision, however, much like using only a zoom lens on a camera limits our view of a photographic subject by focusing on one aspect of that subject. Broadcasters at sporting events typically place cameras at several spots around the field of play, some shooting close-up shots, others from a distance, all filming the action from a variety of angles and perspectives. I was struck by this recently when watching a soccer game on television. Due to technical difficulties, only one of the dozen or so cameras was operational during a 5-minute portion of the game. During that time, the single camera simply followed the ball from one side of the field, up and down the field as the game continued. Consistent with the old saying “You don’t know what you’ve got til it’s gone,” I was struck by the fact that many of the most interesting elements of the game were out of view—defensive positioning, reactions of various defensive and offensive players, their coaches and, of course, the spectators. Although I could watch what would be considered the main part of the game (i.e., where the ball went), ignoring the other elements made for a limited and much less interesting viewing experience. The contrast was striking when the other cameras came back in use. Filming the subject from a variety of angles and perspectives provided a much more complex, full, and informative view. Seeing the field from many different angles, watching the players who were not controlling the ball, seeing the expressions of the coaches and the spectators shed insights into various aspects of the event and, as a result, made for a more rich, interesting, and rewarding experience. This experience highlighted for me the value of multiple perspectives.

The usefulness of multiple theoretical perspectives and “metatheory” has been widely debated in recent years. The debate centers largely on the extent to which a scholar should “choose” or commit to a particular theoretical perspective, or develop an understanding of multiple theoretical perspectives and conduct research on a particular phenomenon, such as workplace relationships, from varying perspectives. In the field of communication, Sheperd, St. John, and Striphas (2006), for example, claim an “unapologetically stubborn suspicion that communication theorists have become a bit too open minded with regard to perspectives on communication” (p. xi). While recognizing various theoretical perspectives, these authors argue that scholars generally experience resonance and commit to a particular theoretical perspective, and rightly so. Craig (1999), on the other hand, highlights the practicality and usefulness of understanding and accepting multiple theoretical perspectives and the insights each perspective can provide on a single phenomenon, such as workplace relationships. While a scholar is not required, nor even strongly encouraged to study a particular phenomenon from multiple perspectives, understanding the assumptions and value of varying perspectives can lead to a group of scholars studying that phenomenon from multiple perspectives and together developing a rich, deep, and complex body of knowledge about that phenomenon.

This orientation toward complementary holism (Albert et al., 1986) acknowledges multiple and interconnected frameworks that together provide a rich and complex context for understanding social reality. It is this orientation that guides this book and my treatment of workplace relationships. While my own research is grounded primarily in postpositivist and social construction theory, I appreciate the insights provided by colleagues who address workplace relationships from other theoretical perspectives. My appreciation is enabled, however, by my ability to understand their work and recognize the fundamentally unique conceptualizations of organizations, communication, and relationships that ground their research. Moreover, I don’t just appreciate work grounded in other perspectives; I actively seek it out as I try to develop rich and more nuanced understandings of workplace relationships. This book is an attempt to encourage other scholars from various disciplines and perspectives to enter into a community of scholars studying workplace relationships from multiple theoretical perspectives.

As mentioned in the preface, one goal of this book is to provide a comprehensive discussion of existing workplace relationship research. Another goal, and the primary purpose of this chapter, is to show how considering workplace relationships from multiple perspectives, each valuable in its own right, can greatly enrich our understanding of workplace relationships and their role in organizational processes. Each perspective provides unique conceptualizations of organizations, communication, and relationships. These conceptualizations drive different research foci, each of which provides important insights. Each perspective draws practitioners’ attention to different elements of an organizational phenomenon or situation. Thus, broadening our theoretical lenses can provide a more thorough and complex understanding of workplace relationship issues and dynamics, and this broadened understanding can enrich both research and practice.

Communication scholars have organized theoretical perspectives and traditions using a variety of organizing systems. Craig (1999, 2007) focuses on seven primary theoretical traditions that subsume virtually all areas of communication. More specific to organizational communication, Deetz (2001) categorized research into four primary perspectives or approaches: postpositivist, interpretive, critical, and postmodern. May and Mumby (2005) broadened Deetz’s system by adding rhetorical, social construction, globalization, and structuration theory. I rely on a synthesis of Deetz (2001) and May and Mumby (2005) for this book, organizing each chapter around postpositivist, social construction, critical, and structuration theories. I chose these theoretical perspectives for a variety of reasons. Space limitations preclude me from discussing all possible theoretical perspectives. I, therefore, chose what I believe are the most widely used and most influential for the organizational communication discipline and potentially most useful for studying workplace relationships.

More specifically, postpositivism is largely recognized as the “dominant theoretical frame for studying organizations” (Mumby & May, 2005, p. 4). As seen in the remaining chapters of this book, the postpositivist perspective guides the bulk of workplace relationship research. I include social constructionism because it was the foundational theoretical perspective for the “interpretive turn” taken in organizational research (Mumby & May, 2005). The interpretive turn represented a watershed moment for organizational scholars (Deetz, 2001) in that the move from studying “communication in organizations” to studying “communication as constituting organizations” radically changed how we study communication and organizations (Allen, 2005). Social constructionism also grounds the other two theoretical perspectives covered in this book—critical theory and structuration theory.

Scholars began using critical theory in organizational research primarily in the 1980s as a rejection of the field’s “managerial bias.” Instead, individuals are given primacy and issues of power, politics, control, and marginalization received attention. This was another important paradigmatic shift for the field that warrants inclusion in this volume. Although scholars disagree on whether feminist theory is a distinct theoretical perspective or a subset of critical theory (Ashcraft, 2005), I include it with critical theory because of its roots in that tradition. Finally, structuration theory (which in many ways is rooted in postpositivism, social constructionism, and critical theory) is included because of the theory’s enormous influence on organizational research over the past three decades, and because it combines aspects of the other three perspectives in novel and important ways.

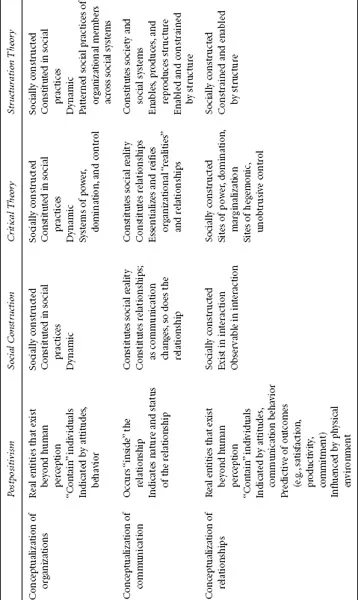

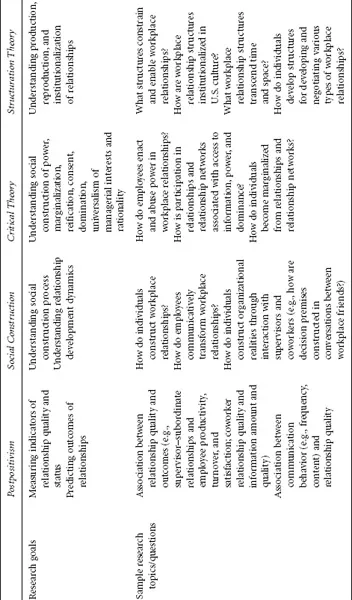

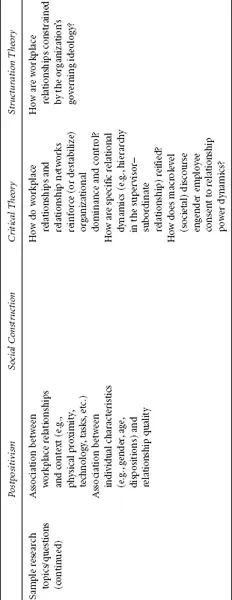

In the following sections, I discuss the primary assumptions of each perspective, how each perspective conceptualizes organizations, communication, and workplace relationships, and the research agendas that are guided by those conceptualizations. Table 1.1 summarizes this discussion.

Postpositivist Approaches to Workplace Relationships

Postpositivism is rooted in the scientific method. It derives from positivism and developed in response to a variety of criticisms leveled against positivism during the 20th century. Similar to positivism, postpositivism is primarily concerned with the search for causal relationships that enable us to predict and control our environments (K. I. Miller, 2000). Postpositivism departs from positivism in a variety of ways, however. Corman (2005) recently provided an excellent summary of these debates and of postpositivism, and delineated several basic principles of postpositivism that guide theory and research in organizational communication.

According to the postpositivist perspective, the social sciences and the natural sciences, although not isomorphic, are united. That is, social beings occupy and operate in physical space (Corman, 2005). Human beings are physical objects and can be physically observed, much like other aspects of nature such as flora and fauna. This naturalism principle has important implications for research. First, because humans are physical objects, human behavior is observable and, therefore, can be measured and evaluated. Thus, postpositivist research focuses attention on human behavior. Second, as physical objects, individuals’ behaviors affect, and are affected by, the physical world. Consequently, postpositivists are drawn to studies that identify causal linkages between the social and natural world, such as how physical proximity impacts human relationship development (Sias & Cahill, 1998). Third, conceptualizing human beings as physical objects who occupy space in the natural world leads to the conceptualization of organizations as “containers” in which individuals carry out their work (R. C. Smith & Turner, 1995). Thus, while the naturalist principle unites the social and physical world, it also bifurcates the two by placing people (the social world) inside physical locations such as organizations (the physical world).

Table 1.1 Theoretical Perspectives onWorkplace Relationships

Postpositivism takes a realist stance, assuming a social reality exists, although we as human beings cannot actually see it. This principle stands in contrast to the positivism’s antirealist stance that perceptions are what matter. Moreover, despite the fact that reality exists outside our perceptions, we can, and should, study that reality. Transcendental reasoning allows us to believe in the reality of things we cannot directly observe based on observing conditions that indicate the existence of something else (Corman, 2005). For example, although we cannot actually see or directly perceive organizations, we believe they exist because they are indicated in other observable phenomena, specifically observable coordinated human behavior.

Together, the postpositivist principles of naturalism and realism imply that reality exists, but is not directly observable. However, human beings, as occupiers of the natural, real world, are observable. To understand “reality,” we must examine indicators of that reality. Thus, to understand the reality of an organization, we must examine indicators of that reality by observing human behavior. So, for example, we cannot see and directly study an organization’s culture; however, the culture is indicated by employee behaviors and attitudes, which we can observe and assess. Communication is conceptualized, then, as an indication of a reality that otherwise transcends our perceptions. Communication is an observable, measurable act that indicates reality. Accordingly, postpositivist studies of organizational communication typically assess communication to understand and predict something else (e.g., organizational culture).

A postpositivist approach to workplace relationships functions similarly. From this perspective, the workplace relationship is an entity that exists in a reality that transcends our perceptions, but is indicated by observable indicators. Such indicators include individual self-report assessments (e.g., a measure of supervisor–subordinate relationship quality). They also include assessments of communication, such as self-reports of the frequency with which individuals communicate with one another, topics about which they communicate, their satisfaction with their communication with a coworker, and the like. Postpositivist research also can include observations of actual communication that indicate relationship status.

In sum, postpositivist studies of workplace relationships conceptualize relationships as “real” entities that transcend our perception. These entities “contain” the relationship partners who behave in specific and patterned ways in those relationships.

Workplace relationship research guided by postpositivism addresses a number of interesting and important issues. Postpositivist research assesses the nature of workplace relationships by examining observable indicators of the relationship such as communication and attitudinal measures. Accordingly, postpositivist research on workplace relationships examines issues such as how certain communication practices indicate and predict relationship quality, and how relationship quality or quantity predicts observable organizational outcomes such as employee satisfaction, productivity, career advancement, and the like. Postpositivist research also examines links between workplace relationships and the context in which they exist. For example, scholars have studied the impact of workplace characteristics such as proximity, climate, and workload on friendship development (Sias & Cahill, 1998). In addition, following the naturalism principle, scholars have examined the ways employees’ physical attributes, such as biological sex, are associated with their relationships ...