- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Agenda-Setting

About this book

What is the biggest social problem in the news today? Who makes issues newsworthy and important? Why do some issues receive more attention than others? Social issues that are widely recognized in the media?s agenda often demand attention on the public agenda and in turn, slide up the policy agenda, creating policy changes. James W. Dearing and Everett M. Rogers?s research on social issues that hit the top of the media agenda--the war on drugs, drunk driving, the Exxon Valdez, AIDS, and the Ethiopian famine--provides important theoretical and practical insight into the agenda-setting process and its role in effecting social change. This reader-friendly volume introduces students to an important area of communication research and offers them direction for further inquiry. Researchers and professionals in political and mass communication, media studies, research methods, and marketing will appreciate this volume?s insightful approach to agenda-setting and policy. "Agenda-Setting is a very useful introduction to the topic as well as a through review of the stream of research. . . . This book introduces a number of ideas that are useful in public relations strategic planning such as the concept of an issue life cycle. A lag/lead analysis of issue development is discussed that would also prove useful to campaign planners. The concept of framing is introduced as a technique that brings meaning to an issue." --Public Relations Review "Authors James W. Dearing and Everett M. Rogers explain the importance of the agenda-setting hypothesis in mass communication research and suggest how research can be advanced in the future. . . . In the book?s most impressive character, the authors raise 12 research issues to advance agenda-setting, including the need for more international, comparative approaches. A very complete list of references and a separate list of suggested readings are helpful to scholars. Highly recommended for all serious collections in journalism, mass media, mass communication, political science, and public policy research." R. A. Logan in Choice

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

SAGE Publications, IncYear

1996Print ISBN

9780761905639, 9780761905622eBook ISBN

9781506320304COMMUNICATION CONCEPTS 6

AGENDA-SETTING

JAMES W. DEARING

EVERETT M. ROGERS

EVERETT M. ROGERS

1. What Is Agenda-Setting?

The press may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about.

Bernard Cohen (1963, p. 13)

The definition of the alternatives is the supreme instrument of power.

E. E. Schattschneider (1960, p. 68)

Every social system must have an agenda if it is to prioritize the problems facing it, so that it can decide where to start work. Such prioritization is necessary for a community and for a society. The purpose of this book is to help readers understand the agenda-setting process, its conceptual distinctions, and how to carry out agenda-setting research.

Agenda-Setting as a Political Process

What is agenda-setting? The agenda-setting process is an ongoing competition among issue proponents to gain the attention of media professionals, the public, and policy elites. Agenda-setting offers an explanation of why information about certain issues, and not other issues, is available to the public in a democracy; how public opinion is shaped; and why certain issues are addressed through policy actions while other issues are not. The study of agenda-setting is the study of social change and of social stability.

What is an agenda, and how is one formed? An agenda is a set of issues that are communicated in a hierarchy of importance at a point in time. Political scientists Roger Cobb and Charles Elder (1972/1983) defined an agenda in political terms as “a general set of political controversies that will be viewed at any point in time as falling within the range of legitimate concerns meriting the attention of the polity” (p. 14). Although we conceptualize an agenda as existing at a point in time, clearly agendas are the result of a dynamic interplay. As different issues rise and fall in importance over time, agendas provide snapshots of this fluidity.

Cobb and Elder (1972/1983) defined an issue as “a conflict between two or more identifiable groups over procedural or substantive matters relating to the distribution of positions or resources” (p. 32). That is, an issue is whatever is in contention (Lang & Lang, 1981). This two-sided nature of an issue is important in understanding why and how an issue climbs up an agenda. The potentially conflictual nature of an issue helps make it newsworthy as proponents and opponents of the issue battle it out in the shared “public arena,” which, in modern society, is the mass media. The issues actually studied by agenda-setting scholars and reported in this volume, however, display the two-sided nature claimed by Cobb and Elder (1972/1983) only to a certain degree. For example, the abortion and gun-control issues seem to be definitely two-sided and conflictual. Certain other issues, such as the environment or drug abuse, seem to be more one-sided in that no one takes a public stand in favor of pollution or greater use of drugs. Even for these issues, however, issue opponents do exist who actively campaign for less attention and funding being given to an issue such as cancer prevention so that greater resources can be given to another issue that they are promoting on the national agenda. Yet there is another important aspect of an issue in addition to conflict. There are many social problems that never become issues even though proponents and opponents exist. Problems require exposure—coverage in the mass media—before they can be considered “public” issues.

Thus, we define an issue as a social problem, often conflictual, that has received mass media coverage. Issues have value because they can be used to political advantage (Ansolabehere & Iyengar, 1994). Although conflict is often what makes a social problem a public issue, as in the case of abortion, valence issues only have one legitimate side, such as drug abuse or child abuse (Baumgartner & Jones, 1993; Nelson, 1984). No one is publicly in favor of child abuse. For valence issues, proponents battle over how to solve the agreed-upon social problem and not whether a social problem exists.

The perspective of Cobb and Elder (1972/1983) and Lang and Lang (1981) that an issue is two-sided and involves conflict reminds us that agenda-setting is inherently a political process. At stake is the relative attention given by the media, the public, and policymakers to some issues and not to others (Hilgartner & Bosk, 1988). We can think of issues as “rising or falling” on the agenda or “competing with one another” for attention. Issue proponents, individuals or groups of people who advocate for attention to be given to an issue, help determine the position of an issue on the agenda, sometimes at the cost of another issue or issues. Agenda-setting can be a “zero-sum game” because space and time on the media agenda are scarce resources (Zhu, 1992a). But sometimes, a hot issue does not supplant coverage of other issues, especially related issues (Hertog, Finnegan, & Kahn, 1994).

An issue proponent might be a newsperson covering a famine in an African nation who shoots a spectacular 3½-minute news story in a refugee camp that is broadcast on U.S. evening television news. Because of the investment of time, effort, and firsthand experience, the reporter becomes a proponent of the famine as an important issue worthy of news attention and public concern. Attention to an issue, whether by media personnel, members of the public, or policymakers, represents power by some individuals or organizations to influence the decision process. The reporter covering the famine may have been influenced to shoot the story from a certain perspective because of discussions with a foreign government official who was frustrated with his or her country’s lack of response to the famine. The visual power of the video footage, in turn, may influence an editor’s decision about the relative importance of the famine news story in relation to other possible news stories. The news, when broadcast, influences millions of people in a variety of ways. Thousands of television viewers call an 800 telephone number to donate money and food. Some viewers work to change U.S. foreign policy about disaster relief to the African nation. A Senate staff member drafts legislation in the name of her boss. Hundreds of newspaper editors and other media gatekeepers decide that the famine deserves prominent news coverage. Several newspaper readers write letters to the editor to protest U.S. government food aid in the face of poverty in America. Thus, the famine becomes a two-sided issue. Within a few weeks, the very real but little-known famine problem is transformed into the “famine issue” and climbs to the top of the media agenda in the United States. The reporter gets a promotion.

The famine may continue to attract attention or it may not, depending on (a) competition from other issues, each of which has its proponents, and (b) the ability of proponents of the famine issue to generate new information about the famine so as to maintain its newsworthiness. So, whether we study television producers, interest group activists, or actions by U.S. senators, the process of influence, competition, and negotiation as carried out by issue proponents is a dynamic driving the agenda-setting process. Most communication scholars have not conceptualized agenda-setting as a political process. A better understanding of the agenda-setting process lies at the intersection of mass communication research and political science. Agenda-setting can directly affect policy.

The issue of cigarette smoking is a dramatic example of the agenda-setting process. Prior to 1970, smoking was a major social problem in America, with millions of people dying of cancer. It was not, however, an important public issue. Then, over the next 25 years, 30 million Americans quit smoking! How did this problem become an issue? The antismoking issue got on public agendas (for instance, citizens groups lobbied for legislation to force the airline industry to ban smoking on all flights), on media agendas (fewer characters, both heroes and villains, now smoke in prime-time television shows), and on policy agendas (the city of Los Angeles pioneered in banning all smoking in restaurants, a policy that spread to other cities). The social norm against smoking became accepted as a result of media advocacy, the strategic use of the mass media for advancing a public policy initiative (Wallack, 1990). Issues previously perceived to be the problems of individuals (“I don’t like it when people smoke while I am eating”) are redefined as a public problem requiring governmental remediation (“Restaurants should be required to offer nonsmoking sections”). Successful media advocacy essentially puts a specific problem, framed in a certain way, on the media agenda. Exposure through the mass media allows a social problem to be transformed into a public issue.

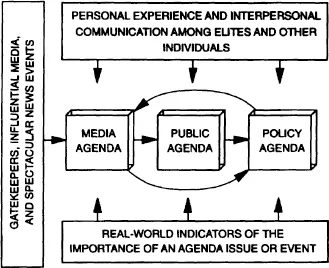

Figure 1.1. Three Main Components of the Agenda-Setting Process: The Media Agenda, Public Agenda, and Policy Agenda

SOURCE: Rogers and Dearing (1988).

Media personalities and organizations engage in issue advocacy. For example, will the aggressive overseas marketing by U.S. cigarette manufacturers (that has led to more young smokers in Third World countries) become a public issue in the United States? Purposive attempts at agenda-setting by media personalities and organizations are often unsuccessful. Members of the U.S. media audience frequently reject the media’s agenda of important issues. People “co-construct” what they see, read, and hear from the media with information drawn from their own lives (Neuman, Just, & Crigler, 1992) to create a meaning for some issue.

The Media Agenda, Public Agenda, and Policy Agenda

The agenda-setting process is composed of the media agenda, the public agenda, and the policy agenda, and the interrelationships among these three elements (Figure 1.1). A research tradition exists for each of these three types of agendas. The first research tradition is called media agenda-setting because its main dependent variable is the importance of an issue on the mass media agenda. The second research tradition is called public agenda-setting because its main dependent variable is the importance of a set of issues on the public agenda. The third research tradition is called policy agenda-setting because the distinctive aspect of this scholarly tradition is its concern with policy actions regarding an issue, in part as a response to the media agenda and the public agenda.

So, the agenda-setting process is an ongoing competition among the proponents of a set of issues to gain the attention of media professionals, the public, and policy elites. But agenda-setting was not originally conceptualized in this way.

The Chapel Hill Study1

The term agenda-setting first appeared in an influential article by Maxwell E. McCombs and Donald L. Shaw in 1972. These scholars at the University of North Carolina studied the role of the mass media in the 1968 presidential campaign in the university town of Chapel Hill, North Carolina. For their study, they selected 100 undecided voters because these voters were “presumably those most open or susceptible to campaign information.” These respondents were personally interviewed in a 3-week period during September and October 1968, just prior to the election. The voters’ public agenda of campaign issues was measured by aggregating their responses to a survey question: “What are you most concerned about these, days? That is, regardless of what politicians say, what are the two or three main things that you think the government should concentrate on doing something about?” (McCombs & Shaw, 1972). Five main campaign issues (foreign policy, law and order, fiscal policy, public welfare, and civil rights) were mentioned most frequently by the 100 undecided voters, thus measuring the public agenda.

The media agenda was measured by counting the number of news articles, editorials, and broadcast stories in the nine mass media that served Chapel Hill. McCombs and Shaw found an almost perfect correlation between the rank order of (a) the five issues on the media agenda (measured by their content analysis of the media coverage of the election campaign) and (b) the same five issues on the public agenda (measured by their survey of the 100 undecided voters). For instance, foreign policy was ranked as the most important issue by the public, and this issue was given the most attention by the media in the period leading up to the election.

McCombs and Shaw concluded from their analysis that the mass media “set” the agenda for the public.2 Presumably, the public agenda was important in the presidential election because it determined who one voted for, although McCombs and Shaw did not investigate any behavioral consequence of the public agenda.

What was the special contribution of the Chapel Hill study of agenda-setting? The methodologies for measuring the two conceptual variables were not new: Both (a) content analysis of mass media messages and (b) surveys of public opinion about an issue were by then common in mass communication research. McCombs and Shaw’s linking of the two methodologies to test public agenda-setting was not a new contribution either. Twenty years earlier, F. James Davis (1952) had combined content analysis, survey research, and “real-world” indicators in testing the public agenda-setting hypothesis (although Davis had not called the process “agenda-setting”). A real-world indicator is a variable that measures more or less objectively the degree of severity or risk of a social problem. McCombs and Shaw’s contribution was in clearly laying out the agenda-setting hypothesis, in calling the media-public agenda relationship “...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1. What Is Agenda-Setting?

- 2. Media Agenda Studies

- 3. Public Agenda Studies: The Hierarchy Approach

- 4. Public Agenda Studies: Longitudinal Approaches

- 5. Policy Agenda Studies

- 6. Studying the Agenda-Setting Process

- References

- Suggested Readings

- Author Index

- Subject Index

- About the Authors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Agenda-Setting by James W. Dearing,Everett Rogers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.