- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Families and Health

About this book

This interdisciplinary text examines five different components of family health--biology, behavior, social-cultural circumstances, the environment, and health care--and the ways they affect the abilities of family members to perform well in their homes, workplaces, and communities. Special awareness is paid to health disparities among individuals, families, groups, regions, and nations. The author discusses how health of individual families influences our local, national, and global communities. Families and Health argues that family health is not a privilege for the few, but a personal, national, and global right and responsibility.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Families and Health by Janet Grochowski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Families and Their Health

When health is absent, wisdom cannot reveal itself, art cannot manifest, strength cannot fight, wealth becomes useless, and intelligence cannot be applied.

Herophilus of Chalcedon (335 BC to 280 BC, in Durant 1966:638)

____________________

This quote from antiquity is as true in the twenty-first century as when first scribed, yet understanding the dimensions and determinants of health, particularly family health, has never been more challenging as our understanding of the complexity of illness increases. American families confront a paradox of their country, spending more on health care than any other nation on the planet, yet on almost every measure of health status, such as infant mortality and adult longevity, the United States ranks below many developed countries. What can be done to remedy this inconsistency? A first step demands recognition that family health is multidimensional and impacts the interactions of family health determinants. This book offers a plausible, pertinent approach to such recognition. The introduction provides working definitions as well as an interactive Family Health Determinants Model (Figure 1.1), which also serves as a framework for the remaining chapters. Included in this chapter is an overview of the status of family health as well as a description of the theoretical foundation in the evolving concept of family health and well-being. Case studies1 are woven into this and following chapters so as to provide human context to this very dynamic process call family health.

Family Health: Definitions and Determinants

Scholars and practitioners from family and medical sciences, as well as many in the general public, recognize the crucial effect of family health and wellness2 on overall family well-being and quality of life. Many of these same scholars and practitioners agree that family health goes beyond absence of disease and dysfunction, and therefore accept a more multidimensional portrait of being healthy and well.3 In this book, the terms health and wellness will be used interchangeably to mean an ability to live life with vitality and meaning regardless of disease and disability.

Applying this multidimensional definition to family health broadens related concepts of family well-being and health-related quality of life. While defining well-being enjoys strong agreement as a “state of being healthy, happy, or prosperous” (Merriam-Webster Online 2012), health-related quality of life is less easily explained or measured. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), health-related quality of life is how individuals or families or both “perceive physical and mental health over time” (Moriarty, Zack, and Kobau 2003:1). With advances in medical science and technology, the issue of health-related quality of life increasingly challenges patients, their families, health care providers, insurers, educators, along with those in government and business. Families increasingly struggle with questions of not only the availability, access, quality, and cost of health care, but also health-related quality of life issues of survivors and their families. “Is it worthwhile to keep a comatose person alive on a respirator?…Traditional indicators like mortality rates and objective clinical parameters are no longer adequate for answering these questions” (Chen, Li, and Kochen 2005:1). A position that “[e]ventually we are going to have to decide if it’s better to keep people alive, connected to machines at a huge cost, with no hope of recovery or to let move onto as nature had intended” challenges families and the medical field (Meyer 2010:1). Who decides when life is worth living? How to aid families physically, intellectually, emotionally, and socially with such life and death decisions and resulting ramifications? Such are questions increasingly facing families in the twenty-first century. Family health, therefore, is a dynamic process. In response, this book incorporates Perri Bomar’s definition of family health as “encompassing a family’s quality of life, the health of each member, family interactions, spirituality, nutrition, coping, environment, recreation and routines, sleep, and sexuality” (2004:11).

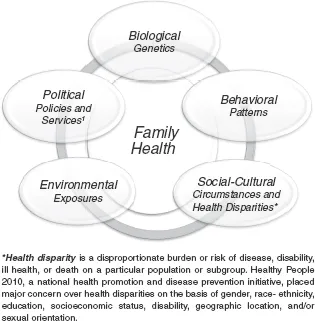

Along with a multidimensional appreciation for family health, there are five interactive determinants that significantly impact health. These interconnected determinants include biological realities (genetics), behavioral patterns, social–cultural circumstances, environmental exposures, and political decisions (health care policy and services). Figure 1.1 provides a model to aid in understanding the dynamic interactive nature of these determinants and their impacts on family health. This model is based on Healthy People 2010 and 2020 concepts, the work from the Board of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention and Institute of Medicine (2002), J. Michael McGinnis, Pamela Williams-Russo, and James Knickman’s (2002) determinants of health, David Kindig’s (2007) Expanded Population Health Model, and Janet Grochowski’s (2010) Family Health Determinants Model.

Figure 1.1 Family Health Determinants Model

Sources: Adapted by author from Grochowski, Janet R. 2010. Families and Health. “Figure 1.1 Family Health Determinants Model.” New York: Allyn and Bacon.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2000:35. “Determinants of Health.” HealthyPeople 2010 Report. Retrieved May 3, 2008 (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hpdata2010/hp2010_final_review.pdf)

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. 2004:28–44. Children’s Health, The Nation’s Wealth. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kindig, David A. 2007. “An Expanded Population Health Model.” Page 4 in ALTARUM Policy Roundtable Report.

The Family Health Determinants Model illustrates some of the complexities involved in family health issues not only due to the interactions among determinants, but also in terms of health equity as revealed in the social–cultural circumstances determinant of Figure 1.1. Health disparities among individuals, families, groups, regions, and nations are glaringly evident in basic local, national, and global health findings (e.g., mortality, morbidity, incidence, or prevalence rates of a disease or illness). Dennis Raphael (2006) argues that such data avoids the causes for such disparities, which he identifies as health inequalities. Health disparities or health inequalities, therefore, are disproportionate burdens or risks of disease, disability, ill health, or death on a particular population or subgroup. Healthy People 2020, a national health promotion and disease prevention initiative, placed major concern over health disparities on the basis of gender, age, race–ethnicity, education, socioeconomic status, disability, geographic location, and sexual orientation.

The health of individual members and their families is determined by these determinants “acting not in isolation but by our experience where domains [determinants] interconnect” (McGinnis, Williams-Russo, and Knickman 2002:83). Genetic predispositions are influenced by behavioral patterns or environmental exposures or both. Families’ behavior patterns and environmental exposures are affected by their social–cultural circumstances and access to quality health care. “Our genetic predispositions affect the health care we need, and our social [cultural] circumstances [environmental exposure and behaviors] affect the health care we receive [or do not receive]” (McGinnis et al. 2002:83). Families, medical and social scientists as well as practitioners need to appreciate these dynamic interactions in the family health process. The following story about Tyra and her family provides an opportunity to identify these determinants and the impacts of interactions on this family’s health and well-being.

Case 1.1 Tyra: Influences on Family Health

As an energetic 42-year-old, Tyra thought she was in good health. Well, perhaps she could lose a few pounds, but she worried more about her husband Gabe’s high blood pressure and their twin daughters’ asthma than about her own health. She knew she should stop smoking, eat better, and get some exercise, but there never seemed to be enough time. Gabe and she both worked full-time at low-paying jobs with neither position providing adequate health care coverage, so regular adult health checkups simply didn’t happen. Tyra knew she had high blood pressure and a family history of stroke, but again like most adults, she thought of heart disease and stroke as male health issues. The air quality of the neighborhood they lived in exasperated their daughters’ asthma and caused the girls to stay inside rather than play outdoors. This environmental exposure added to the strain of the girls’ chronic illness plus fears over losing the children’s Medicaid coverage heightened Tyra’s stress level to where she often couldn’t sleep through the night. The stress on both Gabe and Tyra also wounded their marriage and intimacy as they fought more and communicated less. Neither Tyra, nor anyone else in her family, thought she might have a serious health condition, so when the event happened it was sudden and without warning. Tyra returned from work just as Gabe was leaving for his job. She felt dizzy and a terrible headache pounded as she climbed the stairs to their drab apartment. Fumbling with her keys, panic gripped her as she realized her left side was numb. Falling like a rag doll, she hit the dirty floor, dropping a bag of groceries and breaking a jar of spaghetti sauce she had picked up for dinner. Hearing breaking glass, Gabe raced into the hallway and found Tyra crumpled on the floor, unable to speak or move her left side. The next-door neighbor peeked out into hallway and called 911 as Gabe carried Tyra into their apartment. Unfortunately for Tyra and her family, the ambulance was delayed in responding and the hospital Tyra was taken to did not have a primary stroke center, so while they were able to save Tyra’s life, they could not minimize the extent of damage caused by the stroke. After treatment in the intensive care unit, Tyra stayed in the hospital a few days before being discharged. Tyra was fortunate to have survived since each year twice as many women die from stroke than breast cancer. Yet, African Americans ages 20 to 44 years are 2.4 times as likely to have a stroke and twice as likely to die from a stroke as non-Hispanic whites (National Stroke Association 2012). Tyra lived, but suffered from severe stroke-related disabilities that forced her to quit her job and begin physical therapy in hopes of regaining her speech and improve movement of her left side. Her inadequate health insurance only covered a fraction of the cost of the needed physical therapy and provided very limited coverage for mental health needs. Family health, however, is more encompassing than physical illness and disability. While the physical trauma subsided, the psychological and social issues intensified as Tyra and her family struggled with the anxiety over the loss of income, adjustments to shifting household and parenting roles, Tyra’s growing depression over her disability, plus trying to deal with the increasing stress of staggering medical bills.

All five determinants (see Figure 1.1) significantly impacted Tyra’s family health and well-being. Consider Tyra’s genetic predisposition to stroke and how that may have been impacted by her behavior patterns. Their daughters’ asthma may have been influenced by inside (e.g., poor ventilation, secondhand smoke) and outside (air pollution) environmental exposures. Considering Tyra’s and Gabe’s family health histories of high blood pressure and stroke, they both should have had access to regular preventative health care, yet several social–cultural determinants (e.g., socioeconomic status, geographic location) served as barriers to the health care they needed. While this family had strengths, such as a loving relationship and some health coverage, the challenges posed by interactions among the five determinants negatively swayed the quality of this family’s health and well-being. Chapters 2 through 6 will examine each of these five determinants, with Chapter 4 focusing on the impacts of health disparities. Serving as a foundation for these later chapters, the following sections offer a glimpse at the status of family health in the United States as well as a brief review of the theoretical foundation of this multidimensional, interactive process called family health. One of the first steps in understanding this dynamic process is measuring the health status of American families.

The Status of American Families’ Health

Life expectancy and infant mortality are fundamental measures of health. In 2010, Americans experienced their highest life expectancy measure at 78.7 years. Yet, this increase lacked equity as sex and black and white race disparity gaps continued, with white females living almost a decade longer than black males: white females (81.3 years), black females (78.0 years), white males (76.5 years), and black males (71.8 years). Life expectancy among Hispanic females (83.8 years) is the highest while Hispanic males (78.8 years) lived longer than their white and black male peers (Murphy, Xu, and Kochanek 2012:30–40). On a global scale, this increase in the American overall life expectancy (78.7 years) was still meager when compared with other developed nations. When comparing 35 developed nations that comprise the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), American families fell near the bottom with 26 nations ranking higher in longer life expectancy at birth (OECD 2012b). Another measure of a nation’s health is its infant mortality rate (deaths per 1,000 live births). Among OECD nations, 30 of 34 had lower infant mortality rates than the United States (OECD 2012a). Even when compared to the larger world community of 231 countries, the U.S. Central ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Series Preface: Contemporary Family Perspectives

- Author Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Chapter 1 Introduction: Families and Their Health

- Chapter 2 Biology and Family Health: Epigenetics and Beyond

- Chapter 3 Behavior Patterns: Families’ Health Choices

- Chapter 4 Social Determinants and Family Health

- Chapter 5 Environmental Exposures and Global Family Health

- Chapter 6 Health Care and Families

- Final Summary Comments

- References

- Index