![]()

1

Political Economy of Aging

A Theoretical Framework

Carroll L. Estes

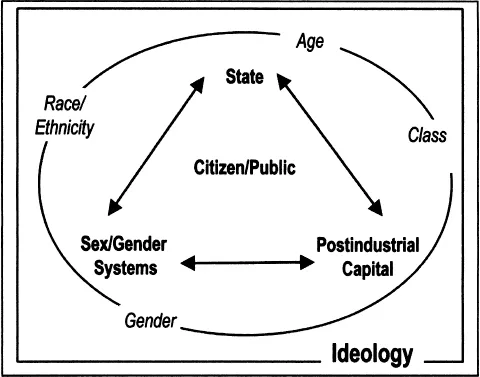

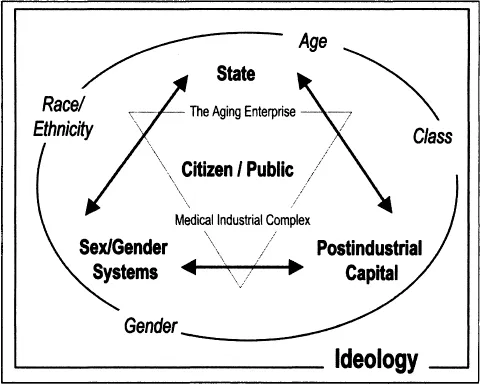

For nearly three decades, application of the political economy perspective has resulted in a more robust understanding of the issues of health and aging by integrating the approaches of economics, political science, sociology, and gerontology, each of which has proven inadequate when employed in isolation. The political economy of aging emphasizes the broad implications of structural forces and processes that contribute to constructions of old age and aging as well as to social policy. It is a systematic view predicated on the assumption that old age can be understood only in the context of social conditions and issues of the larger social order (Estes, 1979; Estes, Gerard, Zones, & Swan, 1984). In addition, the political economy perspective is sensitive to the integral connections between the societal (macrolevel), the organizational and institutional (mesolevel), and the individual (microlevel) dimensions of aging. The framework and approach employed in this volume advance the traditional use of the political economy perspective by refining and expanding prior work done by the author and her colleagues (Estes, 1979, 1999a; Estes, Gerard, Zones, & Swan, 1984). This critical perspective is further informed by new developments in conflict, critical, cultural, and feminist theories (discussed in greater depth in Chapter 2). The theoretical model of the political economy of aging (Figure 1.1) is a multilevel analytical framework that aims to elucidate the socially and structurally produced nature of aging. The conflicting and competitive multidirectional relationships between postindustrial capital, the state, and the sex/gender system create and incorporate new institutional actors, such as “the medical-industrial complex” and “the aging enterprise.” Centered within this model is the public/citizen where the macrolevels and microlevels of analysis are more deeply explored. The power struggles between these institutional forces occur within the context of the “interlocking systems of oppression” (Collins, 1990, 1991) of gender, social class, and racial and ethnic status across the life course (Dressel, Minkler, & Yen, 1999; Street & Quadagno, 1993). Finally, ideology is a key element in defining the issue of aging and determining how policies address aging in society. This chapter explores the unique role that each of these components plays within the theoretical model of social policy and aging. Subsequent chapters explore the complex intersections of these ideas in greater detail.

| Figure 1.1. | Theoretical Political Economy Model: Estes Version |

| Figure 1.2. | Theoretical Model of Social Policy and Aging: Estes Version |

Theoretical Model

The Multilevel Analytical Framework

The analytic levels of the framework are (a) financial and post-industrial capital and its globalization, (b) the state, (c) the sex/gender system, and (d) the public and the citizen (see Figure 1.1). For analytic purpose, the model is expanded to include a fifth level—the medical-industrial complex and the aging enterprise (Estes, 1979), which is a product of the relationship between postindustrial capital, the state, and the sex/gender system (see Figure 1.2). Four of the five levels are adapted and revised from McKinlay (1985). According to conflict theory, discussed in detail in Chapter 2, the actors engage in struggles with one another, and policies result from the extent to which one actor is able to dominate and control the others.

Financial and Postindustrial Capital and Its Globalization

The role of capital in the theoretical model for the political economy of aging is well recognized. One of the most salient contemporary debates about financial and postindustrial capital concerns globalization and the relation of old age policy to the economics and politics of markets and the power of corporate capital around the world. Globalization brings with it the processes of privatization, competition, rationalization, and deregulation as well as the transformation of all sectors of society through technology and the flexibilization and deregulation of work (Castells, 1989; Piven & Cloward, 1997).

William Tabb (1999) depicts the perils of monetary globalization, defined as “cross-border movements” of loans, equities, direct and indirect investments, and currencies. He describes a key process of globalization as the “imperialism of finance” in which there are uncontrolled and extraordinarily rapid movements of capital that may destabilize national economies instantly and that may be likened to Keynes’s classic discussion of the world ruled by a “parliament of banks.” Severe difficulties are inherent in the incapacities of individual nation states to “fix” or “correct” problems that may result from the pressures of financial markets with few controls and little social regulation. When things go wrong, costly bailouts by the state can be expected for financial speculators. Tabb observes that the “logic of [this] financial hegemony” is to “decrease government expenditures and state intervention through privatization and contracting out and do away with capital contributions” (Tabb, 1999, p. 6). This situation produces a “tension between international economic integration and possibilities for progressive politics” (Tabb, 1999, p. 2), the social costs of which are “severe and potentially catastrophic” (Tabb, 1999, p. 3). A case in point in the United States is the pressure to reduce state expenditures and abandon the social contract for the nation’s economic and health security to older persons under Social Security and Medicare. The push has been to replace them with privatized programs. This shifts responsibility from the state to the individual, while also reducing corporate contributions, long seen as “deferred wages,” to these programs.

The current postindustrial time and space is characterized by the “unfolding of information technology with its unlimited horizons of communication” and control, with “telecommunications reinforcing the commanding role of major business concentrations around the world” and in a social system—capitalism (Castells, 1989, pp. 1-2). Castells (1989) identifies two major macroprocesses that are simultaneously occurring: the “restructuring of capitalism” and “information-alism” (p. 4). He hypothesizes that information technologies influence power exercised both by state institutions and by production and management. Both arenas are crucial in the struggles surrounding the politics of aging, the politics of entitlements, and the politics of race, class, and gender because the United States is in an era of electronically manufactured (“virtual”) social movements and the mushrooming of well-funded and conservative think tanks that are applying their media savvy and ingenuity to frame the issues and define the national policy agenda on aging. This combination of capitalism, globalism, and informationalism draws attention to the crucial role of ideological production in U.S. policy debates such as aging. (See the section on ideology in this chapter.)

As a process, debate centers on the “uses” of globalization as the rationale and means by which corporate capital may transnationally pursue new low-wage strategies and weaken the power of labor, women, and minority populations. Globalization extends, perhaps without limits, the corporate capacity of capital to “exit” a nation (and thereby to escape corporate responsibility and/or taxation) in the course of struggles with labor. In this way, globalization offers the possibility of seriously weakening the nation-state. This may be referred to as an opportunity for disciplinary social control of the state by corporate capital—under threat of capital flight elsewhere. At the symbolic and material level, the process of globalization strengthens the irresistibility and power of capital. The inevitability of global market forces and technology challenge the relative power of economics, politics, the state, culture, and social relations more generally.

The State

The state is composed of major social, political, and economic institutions, including the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government; the military and criminal justice systems; and public educational, health, and welfare institutions (Waitzkin, 1983). See Chapter 4 for an additional discussion of state theory.

Offe and Ronge (1982) identify four characteristics of the state in capitalist societies:

- Property is private, and privately owned capital is the basis of the economy.

- Resources generated through private profit and the growth of private wealth indirectly finance the state (e.g., through taxation).

- The state is thereby “dependent on a source of income which it does not itself organize. . . thus [it] has a general ‘interest’ in facilitating” the growth of private property in order to perpetuate itself (Giddens & Held, 1982, p. 192).

- In democracies, political elections disguise the reality that the resources available for distribution by the state are dependent on the success of private profit and capital reinvestment rather than on the will of the electorate.

A fifth attribute of the state is its accountability for the success of the economy; the state bears the brunt of public dissatisfaction for economic difficulties.

O’Connor (1973) and Alford and Friedland (1985) argue that the state in U.S. society has three major functions. First, the state ensures the conditions favorable to economic growth and private profit (allowing for the accumulation of wealth). Second, the state ensures the continuing legitimacy and operation of the social order by alleviating those conditions and problems generated by the free enterprise system (such as unemployment) that might create destructive social unrest. This action is accomplished through the provision of publicly subsidized benefits. Third, the state functions to protect the democratic process (see Chapter 5 for more detail). One problem is that the first two of these functions require the expenditure of public resources. State expenditures that facilitate the accumulation of wealth meet the needs of business and industry through favorable tax treatment and government subsidies: for building industrial parks, for educating and transporting the labor force, and for other investments (such as highways and sewers) that lower production costs. State expenditures for what is traditionally referred to as social welfare reflect the displacement costs of the operation of the economic system—the costs in poverty, sexism, racism, and ageism.

The tension created by the demand for these two different types of expenditures (favorable treatment for business and social welfare) often results in a propensity for the state to spend itself into fiscal crisis. Eventually, this forces the state’s necessary retreat from the fiscal underwriting of the costs of one or both of these functions (O’Connor, 1973). Furthermore, as capitalist industry gets larger and more monopolistic in character, moves into international markets, and advances technologically, the costs of capital formation and reinvestment increase. At the same time, there are increased demands on the state for assistance in meeting those costs (tax subsidies, roads, bridges, toxic waste cleanups, etc.). Although the state subsidizes more of the costs, the benefits of the investments continue to be returned as private profit. In conjunction, because monopoly is not labor intensive, workers are pushed into a diminishing competitive sector. This exacerbates unemployment and increases the need for state subsidies to alleviate the cumulative negative consequences of these processes. From a political economy perspective, the dual functions of public spending are of the utmost importance because the size of the federal budget is viewed not only in nominal terms but also in terms of the complex and competitive interaction between the public and the private sectors of the economy.

Theorists explicitly working on old age and the state include a list of distinguished scholars.1 In a theoretical model for social policy and aging, analysis at the level of the state investigates questions regarding the state’s role in social provision for the aged, in light of the state’s power to (a) allocate and distribute scarce resources, (b) mediate between different segments and classes of society, and (c) alleviate conditions that potentially threaten the social order. Quadagno (1999a) describes the recent shift in the United States to a “capital investment state” characterized by the restructuring of public benefits to coincide with interests of the private sector; the transfer of responsibility from government to the individual and family; and the shift from cash benefits to incentives for saving.

Analysis of public policy directing the allocation and distribution of resources for the nation’s older citizens needs to go beyond the scarcity model. It is not merely a question of whether there are enough resources to support domestic social spending. The more important issue is the actual and perceived impact that allocating an increasing share of resources to the aged has on business and economic growth and on the relations of industry and labor (Myles, 1984). The essential issue, from a political economy perspective, concerns the effect that public spending has on the functions of the private economy in terms of ensuring and maintaining a flow of capital for profits and investments. Conservative economists, for example, have charged that Social Security has reduced the public’s reliance on the market, increased the individual’s dependency on government, and reduced incentives for personal savings, which are a major source of the investment capital essential for economic growth (Rahn & Simonson, 1980). The economic significance of the “graying of America” is that

it increases the size of the public economy and reduces the share of the national income directly subject to market forces. Thus, while population aging is unlikely to break the “national bank” it will alter the bank’s structure of ownership and control. (Myles, 1982, p. 19)

Ultimately, how many resources are controlled by the state or the private economy is a political decision. The relative amounts allocated to supporting the supply of capital (for reinvestment and profit) and to workers or to social welfare costs are never set. However, these allocations are constantly subject to political and economic struggle. Domestic social spending for the needs of income and health compete with other political priorities.

The Sex/Gender System

The third level of the analytic framework advanced in this chapter, the sex/gender system, is a recent addition to the political economy discussion. Although prior work has examined the role of gender at the individual and policy levels, the inclusion of the sex/gender system in the framework as one of the key institutional forces in explaining social policy on aging is new. Prior work of feminist scholars used the term patriarchy to describe the institution of male domination that accompanies the symbolic male principle (Kramarae & Treichler, 1992; Rowbotham, 1981). However, patriarchy has been used to refer more specifically to those relationships at the level of the family, whereas the phrase “sex/gender system” has been proposed to refer to the larger context of male domination and the structures that create and promote domination.2

According to Gayle Rubin (1975), the sex/gender system is a set of arrangements by which society transforms biological sexuality into products of human activity and in which these transformed sexual needs are satisfied. The sex/gender system is reflected in social institutions such as the state a...