- 616 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The SAGE Handbook of Nonverbal Communication

About this book

This Handbook provides an up-to-date discussion of the central issues in nonverbal communication and examines the research that informs these issues. Editors Valerie Manusov and Miles Patterson bring together preeminent scholars, from a range of disciplines, to reveal the strength of nonverbal behavior as an integral part of communication.

Key Features:

Key Features:

- Offers a comprehensive overview: This book provides a single resource for learning about this valuable communication system. It is structured into four sections: foundations of nonverbal communication, factors influencing nonverbal communication, functions of nonverbal communication, and important contexts and consequences of nonverbal communication.

- Represents a wide range of expertise and issues: The chapters in this book are written by contributing authors from across disciplines whose work focuses on nonverbal communication. This interdisciplinary volume explores the points of dissention and cohesion in this large body of scholarship.

- Examines the social impact of nonverbal communication: Nonverbal communication is central to socially meaningful outcomes of communication interactions across all relationship types. This volume shows the importance of nonverbal cues to a range of important personal and social concerns and in a variety of social settings.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The SAGE Handbook of Nonverbal Communication by Valerie Manusov,Miles L. Patterson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

FOUNDATIONS

1

AN HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF NONVERBAL RESEARCH

♦Mark L. Knapp

University of Texas at Austin

One faces the future with one’s past.

—Pearl S. Buck

Long before there were written records, painters, pottery makers, sculptors, dancers, philosophers, leaders, and others, whose work necessitated an understanding of how and why human beings use (or should use) their bodies and with what effect, “researched” nonverbal communication. Walking styles, gestures, forms of handshaking, and other nonverbal behavior practiced centuries ago can be pieced together by examining a variety of written documents, including diaries, plays, histories, folklore, legal codes, and traveler’s accounts (Bremmer & Roodenburg, 1991). In this chapter, I focus only on those written works or scholarly movements that have had widespread influence and/or key issues associated with nonverbal studies that serve as important links in a chain leading to the modern study of nonverbal behavior and nonverbal communication.

♦Rhetoric and the Delivery Canon

The words of the philosopher Confucius (1951/ca. 500 BCE), who expounded on the ways to lead a good life, aesthetics, politics, etiquette, and other topics more than 2,500 years ago, have been preserved. In these records, we find his commentary on communicating without words:

- He said: I’d like to do without words.

- Tze-Kung said: But, boss, if you don’t say it, how can we little guys pass it on?

- He said: Sky, how does that talk? The four seasons go on, everything gets born. Sky, what words does the sky use? (p. 87, Book 17, XIX).

Confucius also made observations repeatedly on what, today, we would refer to as the coordination of verbal and nonverbal signals: for example, “3. There are three things a gentleman honors in his way of life: … that his facial expression come near to corresponding with what he says” (p. 35, Book 8, IV), and

He said: elaborate phrases and expression to fit [insinuating, pious appearance] self-satisfied deference; Tso Ch’iuming was ashamed of; I also am ashamed of ’em. To conceal resentment while shaking hands in a friendly manner, Tso-Ch’iuming was ashamed to; I also am ashamed to. (p. 22–23, Book 5, XXIV)

At about the same time Confucius was proffering his advice in China, philosophers and scholars in Athens and Sicily initiated the publication of the first handbooks on oral rhetoric. The study of oral rhetoric or persuasive speaking is an important tributary of nonverbal knowledge because an understanding of a speaker’s gestures, posture, and voice are central to an understanding of their effectiveness. Aristotle and other Greek rhetoricians thought of rhetoric as having five canons: invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery (Kennedy, 1963). In offering these canons, Aristotle (1991/ca. 350 BCE) established the importance of the nonverbal behaviors involved in delivering a speech, saying that sometimes delivery exerts more influence than the substance of the speech.

But it was the Roman orators and teachers who refined, clarified, categorized, and expanded on the behaviors involved in speech delivery (Kennedy, 1972). Cicero (1942/ca. 55 BCE) established a connection between nonverbal behavior and emotion: “For nature has assigned to every emotion a particular look and tone of voice and bearing of its own” (Section 216). He also addressed the relative influence of various channels when he said, “In the matter of delivery which we are now considering the face is next in importance to the voice; and the eyes are the dominant feature of the face” (Section 222). And like Confucius, Cicero underlined the need for congruence of verbal and nonverbal signals: “For by action the body talks, so it is all the more necessary to make it agree with the thought” (Section 222).

Another Roman rhetorician, whose influence on later rhetorical scholars extended hundreds of years after his death, was Quintilian (1922/90 CE). Quintilian, like those before him, argued for the “harmony” of speech, gesture, and face, but he justified his recommendation by saying that incongruent signals will “not only lack weight, but will fail to carry conviction” (chap. III, 67). He also discussed the role of an orator’s dress (chap. III, 137ff) and made an attempt to classify gestures into two broad categories:

The gestures of which I have thus far spoken are such as naturally proceed from us simultaneously with our words. But there are others which indicate things by means of mimicry. For example, you may suggest a sick man by mimicking the gesture of a doctor feeling the pulse, or a harpist by a movement of the hands as though they were plucking the strings. (chap. III, 88)

An early attempt to ascribe meaning to various nonverbal signals is also found in Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria. In this text, for example, throwing the head back was a behavior that was believed to assist in expressing arrogance and the eyebrows were depicted as showing “anger by contraction … cheerfulness by expansion” (chap. III, 69, 80).

Attention to nonverbal behavior associated typically with the delivery canon virtually disappeared during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance when a concern for style predominated. There was, however, a brief treatment of delivery in Thomas Wilson’s The Arte of Rhetorique in 1553. In this book, Wilson discusses “how to speak in a pleasing tone, how to gesture well, and how to pronounce correctly” (cited in Bizzell & Herzberg, 1990, p. 587). In the mid-to-late 1600s, both Wilkins and Fenelon complained about the quality of pulpit oratory, whereas “others offered advice on delivery for preachers and lawyers, with discussions of acting, facial expression, posture, movement, gesture, projection, tone, pace, and modulation” (Bizzell & Herzberg, 1990, p. 649).

But it was the elocution movement that comprised the next major milestone linking nonverbal behavior and the rhetorical canon of delivery. This movement, which began around 1750 and extended into the early 20th century, is not associated normally with important advances in rhetorical thought. But the elocutionists were keenly interested in body movements and vocalizations, and they developed detailed lists of the many ways a body and voice can be used to deliver written speeches and literary works. In his effort to improve British education, Irish actor Thomas Sheridan sought to restore the stature of delivery in rhetorical study. His published lectures on the subject from 1756 to 1762 discuss

what is now standard speech-text material on oral interpretation, vocal expressiveness, and gestures. Words, Sheridan argues, are not the only constituent of language. Expressions and gestures also communicate. Indeed, they are more primitive than words, more natural where words are artificial, more universal where words are national, and more expressive of emotion than the sophisticated language of words. (Bizzell & Herzberg, 1990, p. 650)

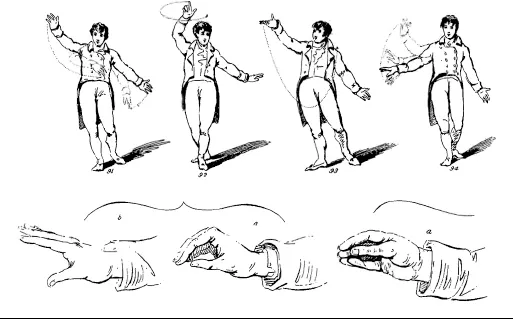

Gilbert Austin (1753–1837), another well-known elocutionist, developed an elaborate notation system with symbols for recording voice speed, force, variety, pausing, over 50 foot movements, over 100 arm positions, and thousands of hand positions, not to mention arm elevation and motion, among other behaviors (Bizzell & Herzberg, 1990). His illustrations from Chironomia (1806) are still reproduced widely (see Figure 1.1). The exceedingly detailed notations represent a significant early contribution toward recording and analyzing nonverbal behavior. But Austin’s approach was not widely accepted as an effective method for learning how to perform while delivering a speech because of the stilted and unnatural behavior it effected.

Elocutionist François Delsarte (1811–1871) also created a system of oratory that detailed body movements (Shawn, 1954). Delsarte’s observation about shoulders is less noteworthy for its accuracy than it is for the implication that nonverbal behavior has a multimeaning potential:

Figure 1.1Illustrations from Austin’s Chironomia

Now the shoulder is limited, in its proper domain, to proving, first, that the emotion expressed by the face is or is not true. Then, afterward, to marking, with mathematical rigor, the degree of intensity to which the emotion rises. (Delaumosne, 1893, pp. 438–439)

Gradually, however, the formal and detailed instruction of the elocutionists gave way to a less formal and research-based approach to delivery in 20th-century public speaking texts. Speech delivery in modern public speaking textbooks is girded with theories, findings, and citations from scholars whose work is viewed as central to the study of nonverbal communication (Gronbeck, McKerrow, Ehninger, & Monroe, 1990).

♦The 19th Century: Two Influential Works

Contemporary scholarship focusing on gestures and facial expressions owes a huge debt to two works published in the 19th century: de Jorio’s (1832) Gestural Expression of the Ancients in the Light of Neapolitan Gesturing and Darwin’s (1872/1998) The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Kendon (1982b, 2004), who has researched thoroughly the development of gestural study throughout history, says this about de Jorio’s work: “It remains one of the most complex treatises on the subject ever published and it is the first ever to present a study of gesture from what today would be called an ethnographic point of view” (Kendon, 2000, p. xx).

De Jorio believed that his analysis of the everyday gestural behavior of ordinary people in Naples would help archeologists and others to better understand the gestures depicted on Greco-Roman vases, frescos, and sculptures that were being discovered. In the process, however, he provided much more. Among other contributions, Kendon credits de Jorio for (1) establishing the importance of context in understanding gestures (e.g., the same gesture may take on a different meaning with variations in accompanying facial and bodily activity); (2) identifying ways that gestures function with words and as substitutes for words; (3) treating gesture for the first time “as if it is a culturally established communicative code analogous to language” (Kendon, 2000, p. xx); and (4) an approach to making a gesture dictionary that even today shows more promise than many extant efforts.

Charles Darwin, like de Jorio, was extremely skilled at amassing, describing, and interpreting a wealth of observations. Ekman (1998a) said, “Almost everyone now studying the facial expressions of emotion acknowledges that the field began with Darwin’s Expression” (p. xxviii). One hundred years after Darwin’s observations from largely anecdotal data, scholars using more systematic and rigorous research methods confirmed the validity of many of his observations about the facial expressions of emotion in adult human beings, infants, and other animals (Ekman, 1973; Ekman & Friesen, 1971; Ekman, Friesen, & Ellsworth, 1972).

Darwin was one of the first to study facial expressions in the context of evolutionary principles and one of the first to use photographs to illustrate expressions (see Floyd, this volume). His idea that there was a pan-cultural morphology for certain expressions stimulated controversy among scholars, but it also stimulated research that enabled us to understand better what aspects of an expression are common to our species, the morphology of facial expressions, and how certain aspects of facial expressions of emotion can be modified by cultural teachings (Ekman, 1998b). And whereas he did not discuss the issue of deception at length, contemporary efforts by scholars to study nonverbal expressive behavior during deception are quite compatible with his ideas (Ekman, 2001).

♦The Early 20th Century

At least four key developments during the first half of the 20th century set the stage for what was to be the blossoming of nonverbal studies at midcentury. First, there was a growing interest in human interaction and communication by prominent scholars from many disciplines (Delia, 1987). Symbolic interactionists (e.g., George Herbert Mead), researchers interested in group dynamics (e.g., Kurt Lewin, Elton Mayo), propaganda (e.g., Harold Lasswell), cybernetics (e.g., Norbert Wiener), and information theory (e.g., Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver) all took different approaches to communication, but together they made social interaction a key to understanding social life at all levels. This not only opened the door for the examination of myriad behaviors affecting human transactions but also made understanding of human interaction an important and respectable area for disciplines, such as sociology, psychology, anthropology, linguistics, psychiatry, ethology, and speech.

This focus on human interaction occurred at a time when the concern for more scientific approaches to social issues was also gaining strength. Thus, nonverbal research during this period is characterized by the use of more sophisticated and precise procedures for studying and recording behavior, the use of film, and an increasingly innovative variety of methods. According to DePaulo and Friedman (1998), the experimental study of nonverbal behavior by psychologists grew rapidly during this period and by the 1920s “a very active group of researchers was studying spontaneous versus posed facial expression of emotion, vocal expression, and gestures” (p. 6). Anthropologist Eliot Chapple (1940, 1949), for example, began using a mechanical device, called an interaction chronograph, which produced an ongoing graphic record of who talked, when, and for how long. Among other uses, data from this device provided an early glimpse at response matching and interaction synchrony.

In 1930, anthropologist Franz Boas was perhaps the first social scientist to use the motion picture camera to generate data in natural settings with the goal of studying human gestures, motor habits, and dance. Davis (1979) attributes the first microscopic frame-by-frame analysis of filmed movement patterns to Halverson (1931), a child psychologist. During the 1920s, an extremely detailed system for annotating the movements of dancers quantitatively and qualitatively was devised by Rudolf Laban (1926; Hutchinson, 1970). Although nonverbal researchers have not embraced Labanotation (or any other comprehensive whole-body coding system) as a way of recording ongoing human behavior, coding and notational methods are common in nonverbal research.

Given the preceding trends, it is not surprising that David Efron’s (1941) landmark study of gestures employed a variety of innovative methods, including (1) direct observation of natural interaction; (2) filmed interactions, which he studied and from which he elicited perceptions of naive observers; (3) frequency counts, graphs, and charts; and (4) sketches of interact...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Ubiquity and Social Meaningfulness of Nonverbal Communication

- Part I: Foundations

- Part II: Factors Of Influence

- Part III: Functions

- Part IV: Contexts And Consequences

- Part V: Final Thoughts

- Author Index

- Subject Index

- About the Editors

- About the Contributors