![]()

PART I

Entrepreneurial Strategies for the Emerging Venture

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Entrepreneurship and Strategy

A Framework for New Venture Development

A lot of people have ideas, but there are few who decide to do something about them now. Not tomorrow. Not next week. But today. The true entrepreneur is a doer, not a dreamer.

—Nolan Bushnell, founder of Atari and Chuck E. Cheese’s

1. Understand the key role of strategy in the discovery and exploitation of opportunities as entrepreneurial firms form and grow

2. Learn about contemporary trends and patterns in entrepreneurship, including its role in the global economy and the increase in social entrepreneurship

3. Understand the significance of entrepreneurial firms to innovation in the economy

4. Become aware of the key traits and behaviors associated with successful entrepreneurship

5. Learn how a well-established model of strategy (7S model) can be used to develop strategy for emerging organizations

6. Use the Creative Tool: Diagnostics for Entrepreneurial Systems to learn about needs, problems, and changes for an industry in which you are interested

SOURCE: Russell S. Sobel, West Virginia University Entrepreneurship Center. Used with permission.

1. Why, when, and how do opportunities for the creation of goods and services come into existence?

2. Why, when, and how do some people and not others discover and exploit these opportunities?

3. Why, when, and how are different modes of strategic action used to exploit entrepreneurial opportunities?

What is the relationship between entrepreneurship and strategy? Both entrepreneurship and strategic management focus on the ways in which businesses create change by exploiting opportunities they discover within the uncertain environments in which they operate (Ireland, Hitt, & Sirmon, 2003). Entrepreneurs are able to create wealth by identifying opportunities and then developing competitive advantages to exploit them (Hitt & Ireland, 2002; Hitt et al., 2001; Ireland, Hitt, Camp, & Sexton, 2001). Thus, strategic entrepreneurship is the integration of entrepreneurship and strategic management knowledge (Ireland et al., 2003). Successful entrepreneurs are able to notice the possibilities that many other people seem to miss, and, more important, they are then able to find the means to turn these possibilities into action: to bring to the market something novel and useful.

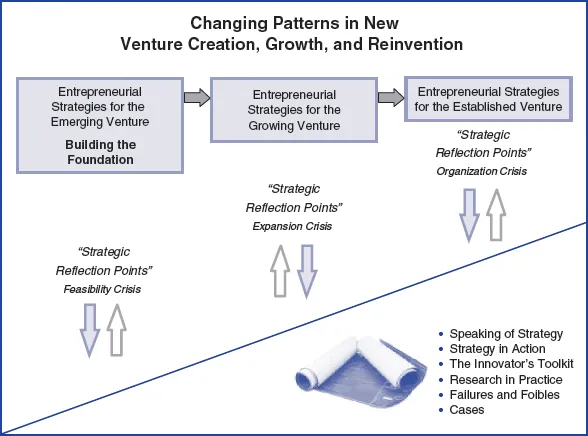

Figure 1.1 Framework for the Book

This textbook presents a framework for strategy in entrepreneurial organizations that incorporates new venture emergence, early growth, and reinvention and innovation in established ventures. The focus of the text is on entrepreneurial strategies that can be crafted and implemented within small and medium-size organizations as these firms proceed through the stages of development. The unique approach of this book is its segmentation of entrepreneurship strategies across the life cycle of business growth. Most strategy texts present content that is segmented by the type or level of strategy (e.g., marketing, human resources, production strategies) rather than the changing pattern of strategic needs faced by the new venture. Finally, the textbook includes opportunities to examine and assess multiple themes and crisis points (labeled Strategic Reflection Points) that can determine the sustainability and growth of the emerging enterprise (see Figure 1.1).

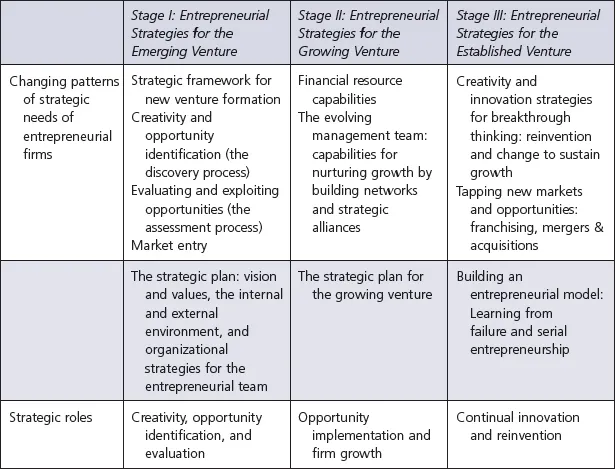

Our book is written from the point of view of the founder or the entrepreneurial team. Increasingly, entrepreneurs are relying on the expertise and input of key stakeholders as they launch and develop their businesses. Whether these stakeholders are outside the firm in the role of advisers or inside in the roles of investors and employees, the entrepreneur’s ability to create a powerful team capable of breakthrough thinking shapes the new venture’s potential success and growth. This book strongly emphasizes the key strategic roles of creativity, opportunity identification, opportunity evaluation and implementation, and continual innovation in the emergence and growth of entrepreneurial firms. Table 1.1 displays these strategic roles, along with the changing patterns and needs of the entrepreneurial firm and the overall strategy and planning initiatives needed to take the firm to the next stage of growth.

Table 1.1 Entrepreneurial Stages: Changing Patterns, Strategies, and Entrepreneurial Roles

Contemporary Entrepreneurship: Trends and Patterns

Emerging businesses are significant players in the world’s economy today. In the United States, they produce about half of the economy’s output, employ half of the private-sector workforce, fill niche markets, innovate, increase competition, and give people in all circumstances a chance to succeed. Across industries, new ventures are confronted by a variety of business conditions, and they tackle them with unique solutions using diverse resources (Small Business Office of Advocacy, 2004).

Entrepreneurial firms can be found in all sizes and in all stages of the life cycle. Over the last decade, small firms have provided 60 to 80 percent of the net new jobs in the economy, and according to the U.S. Bureau of the Census, most of these net new jobs come from start-ups within the first two years of operation (Acs & Armington, 2003). Most of the new employment in the economy continues to be an outgrowth of innovation, the engine that spurs job growth. Schumpeter (1942), one of the first economic scholars to focus on entrepreneurial activities, coined the term creative destruction to describe the phenomenon in which new firms innovate to enter the market and compete with already established businesses, and as a result, some of these older counterparts close due to lower productivity, which has put them at a competitive disadvantage.

Consider the following trends and patterns in recent entrepreneurial activity in the United States (Small Business Office of Advocacy, 2005):

• In 2004, there were about 5.8 million employer firms (nonfarm). From 1995–2003, self-employment increased by 8.2 percent, to a total of 15 million self-employed people. Women represented half of this increase; their share of self-employment was up from 33.1 percent to 34.2 percent.

• Following population trends, self-employment among individuals of Hispanic and Asian/Native American heritage has significantly increased between 1995 and 2003, 65.8 percent and 38.4 percent, respectively. African American self-employment also rose by 20.3 percent during this period.

• In 2004, small business fared well. The number of new employers exceeded those closing their businesses, and the number of self-employed increased.

• Entrepreneurial firms benefited from the continued recovery in the economy in 2004, along with the abundant supply of credit. Small business borrowing increased slightly. Equity investment for later-stage financing was easier to attract than early-stage financing. However, angel investors continued to be important for providing funding to early-stage entrepreneurs in 2004.

• In fiscal year 2004, the federal government granted $69.2 billion, or 23 percent of $299.9 billion in federal prime contracts to small businesses.

Around the world, entrepreneurial activity is thriving. The following findings emerged in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor’s research analysis of 34 countries (Acs, Arenius, Hay, & Minniti, 2005).

• A large number of people are engaged in entrepreneurial endeavors around the globe. About 73 million adults are either starting a new business or managing a young business of which they are also an owner. The average level of activity was 9.3 percent, representing 1 out of every 11 adults around the world.

• Three out of every five people involved in entrepreneurship around the world are opportunity entrepreneurs, defined as participating in entrepreneurial activities to exploit a perceived business opportunity. Opportunity entrepreneurs are more likely to be found in high-income countries.

• Two in five people are necessity entrepreneurs, who pursue entrepreneurship because all other employment options are either absent or unsatisfactory. Necessity entrepreneurs are more likely to be found in low-income countries.

• Young people between the ages of 25 and 34 tend to be involved in entrepreneurial activity in every country studied, more than people of any other age groups. This tended to vary by income levels, and low-income countries saw more activity across all age groups.

• In high-income countries, 57 percent of entrepreneurs have a postsecondary degree, compared to 38 percent in middle-income countries and 23 percent in low-income countries.

In summary, these patterns suggest very strongly that entrepreneurship is alive and vibrant around the globe. Economists agree that entrepreneurship is responsible for much of the competition and innovation in the business world. The innovations introduced by entrepreneurs challenge and make obsol...