eBook - ePub

Prospective Memory

An Overview and Synthesis of an Emerging Field

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Prospective Memory

An Overview and Synthesis of an Emerging Field

About this book

While there are many books on retrospective memory, or remembering past events, Prospective Memory: An Overview and Synthesis of an Emerging Field is the first authored text to provide a straightforward and integrated foundation to the scientific study of memory for actions to be performed in the future. Authors Mark A. McDaniel and Gilles O. Einstein present an accessible overview and synthesis of the theoretical and empirical work in this emerging field.

Key Features:

- Focuses on students rather than researchers: While there are many edited works on prospective memory, this is the first authored text written in an accessible style geared toward students.

- Provides a general approach for the controlled, laboratory study of prospective memory: The authors place issues and research on prospective memory within the context of general contemporary themes in psychology, such as the issue of the degree to which human behavior is mediated by controlled versus automatic processes.

- Investigates the cognitive processes that underlie prospective remembering: Examples are provided of event-based, time-based, and activity-based prospective memory tasks while subjects are engaged in ongoing activities to parallel day-to-day life.

- Suggests fruitful directions for further advancement: In addition to integrating what is now a fairly loosely connected theoretical and empirical field, this book goes beyond current work to encourage new theoretical insights.

Intended Audience:

This relatively brief book is an excellent supplemental text for advanced undergraduate and graduate courses such as Memory, Human Memory, and Learning & Memory in the departments of psychology and cognitive science.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Prospective Memory by Mark A. McDaniel,Gilles O. Einstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Prospective Memory

A New Research Enterprise

The failure of memory that caused me the most pain was the time I forgot to pick up my 3-year-old son and his friends after nursery school and take them to their play group.

—Eugene Winograd, Practical Aspects of Memory

This poignant example refers to an aspect of memory commonly termed prospective memory.* Prospective memory is remembering to carry out intended actions at an appropriate point in the future. Even minimal reflection prompts the realization that the texture of our daily existence is inextricably bound with prospective memory tasks. These tasks include mundane demands such as remembering to pick up bread on your way home, remembering to mail the letter in your briefcase, remembering to give your housemate the message that a friend called, and remembering to load your bicycle into the car for a ride after work. Prospective memory tasks are integrated into our work lives: The waiter must remember to pick up extra cream for a table on his way back to the kitchen, and an instructor has to remember to make sure the reserve readings for her class are available before meeting her seminar. Prospective memory is also involved in activities that are critical to maintaining life. Remembering to take medication is a common example. Failure to remember to check the backseat of the car after an appropriate period of time has elapsed has produced tragic deaths for young children left in the car (see Chapter 9 for discussion of real-world prospective memory challenges).

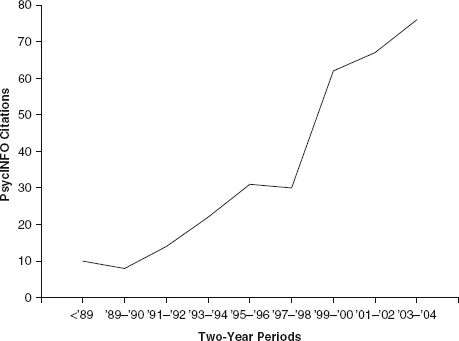

Given the ubiquity and central importance of prospective memory, surprisingly little experimental and theoretical investigation on the topic has been conducted. By comparison, retrospective memory (memory for events that have occurred in the past, such as the plot of a movie seen the previous week, or a list of words studied in an experiment) has been examined and considered thoroughly by experimental psychologists for over a hundred years. What we today call prospective memory was touched upon in early work, but very rarely. A survey of memory published in 1899 by Colegrove included a question on how people remembered to keep appointments, and Lewin’s essay “Intention, Will, and Need” (1926/1961) considered aspects of prospective memory. But by 1985, in sharp contrast to the large amount of available material on retrospective memory, there were only 10 published experimental studies on prospective memory. Most of these studies were reported primarily in edited volumes (Harris, 1984) and had relatively little impact on the mainstream memory literature. It is probably safe to say that many memory researchers were unaware of research concerning prospective memory. It was not a topic mentioned in our graduate training during that era. By 1996, still only 45 published papers had appeared in the entire literature, and of these just about half included experimental work (Kvavilashvili & Ellis, 1996).

But the landscape is changing. The past decade has seen an explosion of experimental research on prospective memory (Kvavilashvili & Ellis, 1996). From 1996 to 2000, approximately 135 published papers appeared, and in the subsequent 5-year span (from 2001 to 2005) over 150 additional studies on prospective memory were published (Kvavilashvili, Kyle, & Messer, in press). As demonstrated in Figure 1.1, citation counts of prospective memory research have shown a parallel upswing. Laboratory paradigms for careful investigation of prospective memory have been developed, papers on prospective memory are appearing regularly in the journals, and important theoretical perspectives are being developed. Researchers from around the world are involved in prospective memory research. Since 2000, there have been two international conferences focused on prospective memory as well as many more-general cognition conferences that have included sessions on prospective memory. Students in many areas of psychology are expressing interest in prospective memory and conducting theses on the topic. Courses on prospective memory are being included in the curriculum in graduate programs. Prospective memory considerations are now included in government-sponsored efforts concerned with such things as aviation safety and space exploration. Although once appropriately characterized as a “forgotten” topic (Harris, 1984), prospective memory is clearly a vibrant topic at the beginning of the 21st century. The primary literature is now sufficient to allow an informed and broad examination of prospective memory, and this book is intended to provide interested researchers and students with an accessible and integrated foundation for the scientific study of prospective memory.

Figure 1.1 The Growth of Prospective Memory Research

SOURCE: From Marsh, R. L., Cook, G. I., & Hicks, J. L., An Analysis of Prospective Memory. In D. L. Medin (Ed.), The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 43, copyright © 2006. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

What Is a Prospective Memory Task?

Our first order of business is to consider what constitutes a prospective memory task. In writing this chapter, we had animated discussions as we struggled with this issue. Here we distill the key features of our thinking with the thinking of others who have grappled with the issue. We started this chapter with a brief definition of prospective memory: remembering to do something at a particular moment (or time period) in the future. For the most part, researchers assume that this brief description activates a fuzzy set (Harris, 1984) that captures a common set of intuitions about what is and what is not a prospective memory task. In a strict sense, this definition can include almost any experimental task.

To illustrate, consider the following experimental task: Subjects are instructed that they will be shown a short word list, after which they will be asked to write down the words in the list. In addition, when some of the word lists are presented, a series of digits will be read concurrently, and subjects are to press a handheld counter every time they hear two consecutive odd digits. Subjects are further told that if they ever encounter the word rake in a word list, they should press the F1 key on the keyboard. In this kind of experiment, researchers have considered pressing the F1 key to be the prospective memory task. Yet a careful reader might justifiably ask, “Why aren’t the other tasks also considered prospective memory tasks?” In all cases, the instructions convey an intended action, and the subject has to perform that action at some time after the instructions are given.

We need to sharpen our characterization of prospective memory to help guide our exploration of the topic and to help delineate our area of inquiry. Most generally, one might think of almost all everyday tasks and all laboratory experimental tasks as having both retrospective memory and prospective memory components. To perform an intended activity, one must remember to recall there was an intention (the prospective component) and also remember the contents of the intention (the retrospective component) (Einstein & McDaniel, 1996; Ellis, 1996; Graf & Uttl, 2001). In everyday contexts, both memory components can be challenged. The intention to stop by the store on your way home from work to pick up five items can be unsuccessful because prospective memory fails (you forget to stop at the store or because retrospective memory fails (you remember to stop at the store, but forget one or several of the items). In the laboratory, however, one component can be minimized so as to isolate the other component for study. The study of memory has historically emphasized tasks in which the prospective memory component is not challenging and the retrospective component is. The subject in a typical experiment does not have to remember to recall an intention to remember the studied items because the experimenter explicitly tells the subject to remember. In Tulving’s (1983) terms, the memory experiment places the subject in a “retrieval mode.” The study of prospective memory changes this emphasis by focusing on the prospective component and minimizing focus on the retrospective component.

In a retrospective memory experiment, the challenge for the subject is to remember the contents (recall the list of words studied). The parameters of laboratory retrospective memory tasks ensure that remembering the contents is challenging, so as to reveal the properties, processes, and dynamics of memory. If we decide to present one word for study and a short time later ask someone to recall that word, all of us would agree that this is a retrospective memory task. But this task likely would not tell us much about retrospective memory. In a similar vein, prospective memory tasks are designed to challenge remembering to recall (whereas the contents to recall are simplified). Paralleling retrospective memory tasks, prospective memory tasks can have a continuum of difficulty, such that remembering to recall can range from easy to challenging. If the demands of the tasks are too easy, we may not have incisive and revealing experiments for scientific study of prospective memory. In the next section, we synthesize the thinking of prospective memory researchers to offer some guidelines for creating interesting and informative prospective memory tasks.

Parameters of Prospective Memory Tasks

Execution of the intended action is not immediate. First, we will agree that, in normal populations, actions that people begin to carry out immediately after the intention has been formed are trivial in terms of prospective remembering (Harris, 1984; Kvavilashvili & Ellis, 1996). When subjects are given the instruction to recall or recognize a list of items and begin doing so, this is immediate execution of the intention. Because remembering to recall is certain, there is no sense of prospective memory here. Of course, these kinds of tasks, including the recall task in the illustrative experiment above, characterize a tremendous amount of the literature on memory.

The prospective memory task is embedded in ongoing activity. Second, a delayed intention—one that must be realized only at some point in the future—is not itself sufficient to produce an interesting or challenging prospective memory task. In the experimental setting, many tasks introduced at some delay after the instructions are given require that initial intentions be postponed. In our example, the intention to monitor for odd digits is postponed until later in the experiment when the digits are presented. These kinds of tasks would not be the focus of prospective memory research because the presentations of the stimuli supporting the intention are implicit, unambiguous signals to perform the instructed activity (see Einstein, Smith, McDaniel, & Shaw, 1997, and Harris, 1984). The presentation of the stimulus essentially serves as a proxy for the instruction. In the experimental setting, the stimulus (the auditorily presented digits) demands a response, thereby requiring that the person recall the instructions, but there is no sense in which the person is challenged to remember at a given moment to recall the instructions.

In contrast, in a typical prospective memory task, the stimulus that signals the appropriate moment for execution of the prospective memory activity does not directly or unambiguously demand performance of the previously intended action. The prospective memory cues (or stimuli) appear as a natural part of another task or situation (see Graf & Uttl, 2001). To achieve this, in laboratory paradigms the prospective memory task is embedded in an ongoing activity. Here the stimuli support performance of the ongoing activity, thereby satisfying the experimental demand to “do something.” In our above example, the presentation of the word rake is part of the ongoing demand to maintain words for a short-term memory test. The prospective memory intention need not be retrieved for the subject to respond in the experiment. Consequently, nontrivial demands are placed on the subject to remember to recall that there is another “something” that must be done. This critical aspect of the prospective memory task occurs regardless of the nature of the retrieval occasion. The occasion can be event based, such as a particular stimulus item (see examples in Cherry & LeCompte, 1999, and Einstein & McDaniel, 1990). The occasion can be time based, such as a particular time or a period of elapsed time during the ongoing activity (d’Ydewalle, Luwel, & Brunfaut, 1999; Harris & Wilkins, 1982; Park, Hertzog, Kidder, Morrell, & Mayhorn, 1997). The occasion can be activity based, such as when a particular experimental activity has been completed (Kliegel, McDaniel, & Einstein, 2000; Loftus, 1971).

As just mentioned, in typical laboratory paradigms the prospective task is embedded in an ongoing activity, and performance of the ongoing activity must be interrupted or suspended to allow execution of the prospective memory task. This aspect captures another feature of prospective memory that some theorists consider to be central: Prospective remembering involves interrupting a daily routine or activity (see examples in Morris, 1992, and Shallice & Burgess, 1991). Other theorists, however, distinguish types of prospective memory tasks on this very dimension. Kvavilashvili and Ellis (1996) acknowledge that event- and time-based prospective memory tasks involve interrupting an ongoing activity, and that such interruptions represent an important component of these types of prospective memory tasks. For example, in remembering to buy bread on the way home from work, one must interrupt the drive home when encountering the grocery store. When remembering to attend a meeting at 11:00 A.M., one must interrupt the ongoing work activity at hand.

In contrast, Kvavilashvili and Ellis (1996) contend that activity-based prospective memory tasks do not require interruption of the ongoing activity, precisely because these tasks are signaled prior to initiation of an activity or upon completion of an activity. For example, remembering to take medication after finishing breakfast involves doing something during the gap between finishing breakfast and initiating the next activity in one’s routine. One might argue, however, that this assertion depends on the extent to which normal, routinized activities are interconnected. For instance, taking medication after breakfast requires interruption of the normal routine of driving to work after breakfast (instead of walking to the car, one must fetch the medication). Similarly, an activity-based task in the laboratory might interrupt the normal flow of experimental tasks. For example, when subjects are asked to remember to request their watches at the conclusion of the experiment (an activity-based prospective memory task) (Kliegel et al., 2000), there is a sense in which the normal routine of departing the laboratory when the last task is completed is...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- 1. Prospective Memory: A New Research Enterprise

- 2. Monitoring in Prospective Memory

- 3. Spontaneous Retrieval in Prospective Remembering

- 4. Multiprocess Theory of Prospective Memory

- 5. Storage and Retention of Intended Actions

- 6. Planning and Encoding of Intentions

- 7. Prospective Memory and Life Span Development

- 8. Cognitive Neuroscience of Prospective Memory

- 9. Prospective Memory as It Applies to Work and Naturalistic Settings

- 10. Final Thoughts

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

- About the Authors