- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Women at Risk brilliantly recasts the debate about violence against women and makes a major contribution to feminist thinking about women?s health. Practitioners and theorists who want to understand women?s health issues from a stunning new perspective must read this book. --Heidi Hartmann, Ph.D., President, Institute for Women?s Policy Research, Washington, DC "Women at Risk is a unique and important blend of research, practice, and advocacy. This volume makes a significant contribution to the health care profession?s understanding of violence against women. This is a long-awaited book by two major scholars and practitioners in the field of violence against women." --Richard J. Gelles, Ph.D., Director, Family Violence Research Program, University of Rhode Island "Women at Risk is a thought-provoking investigation of the violence that may bring women to emergency departments with injuries or suicide attempts. It challenges assumptions that patriarchy causes violence against women and that women are passive victims. And it dares to acknowledge violence by women. It goes beyond a plea for awareness of violence and outlines steps that hospital staff can follow to identify, care for, and advocate for battered women. Evan Stark and Anne Flitcraft strongly affirm the status of wife assault as a public health issue." --N. Zoe Hilton, Ph.D., Mental Health Center of Penetanguishene, Ontario Filled with groundbreaking research, Women at Risk challenges current explanations of domestic violence and argues that reframing health in terms of coercion and violence is key to the prevention of some of women?s most vexing problems. Presenting major findings of studies conducted over 15 years, authors Evan Stark and Anne Flitcraft maintain that the medical, psychiatric, and behavioral problems exhibited by battered women stem from a so-called "dual trauma," in which the coercive strategies used by their partners converge with discriminatory institutional practices. This timely volume explores the theoretical perspectives as well as health consequences of woman abuse and considers clinical interventions to reduce the incidence of homicide, child abuse, substance abuse, and female suicide attempts associated with battering. In addition, the authors progressively promote the notion of "shelter" not as a facility or service, but as a political space to be opened within families, communities, and the economy--a space where toleration for male coercion ends. Medical professionals, mental health practitioners, social workers, and researchers, as well as advanced students in health, psychology, or the social sciences, will find this compelling volume a thorough resource.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women at Risk by Evan Stark,Anne Flitcraft in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicología & Relaciones interpersonales en psicología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Theoretical Perspectives

1

Medicine and Patriarchal Violence

By conservative estimate, 3 to 4 million women are assaulted by male partners each year in the United States and at least four times this number, between 12 and 15 million women, have been assaulted by their male partners in the past (Flynn, 1977; Straus, 1977–1978). In approximately 10% of these cases, the assault is speedily followed by effective protection or permanent estrangement from the aggressor. But there is mounting evidence that the vast majority of these beatings are part of an identifiable pattern of ongoing, systematic, and escalating abuse that often extends over a lifetime (Dobash & Dobash, 1977–1978; Flitcraft, 1977; Gelles, 1974; Pizzey, 1974). We refer to this pattern as woman battering.

In the late 1960s, Parnas (1967) reported that the police received more calls concerning “domestics” than concerning murder, aggravated assault and battering, and all other serious crimes combined. The repeat nature of these calls was illustrated by reports from Kansas City that 80% of the domestic homicides there were preceded by one or more complaints of assault to the police and 50% were preceded by five or more calls (cited in Lachman, 1978). Despite little documentation, victims of domestic violence describe attempting to access other service systems as well. Why then are millions of women trapped in abusive relationships?

A common answer is that little can be done to prevent abuse because it is a “private” event caused by a combination of psychopathology, behavior learned in childhood, a culture that endorses violence as a means for resolving conflicts, and stresses peculiar to family life (Hanks & Rosenbaum, 1977; Renvoize, 1978; Rounsaville, 1977; Snell, Rosenwald, & Robey, 1964; Walker, 1979; Whitehurst, 1971). If women and children are the most obvious victims, the argument goes, this is because they are physically vulnerable and dependent. According to a current psychological theory, the duration of female abuse is explained by learned helplessness, a depressive syndrome evoked by severe and repeated assault and characterized by a reluctance to seek help (Walker, 1979). The paucity of institutional data supports the belief that victims fail to report domestic violence.

Personal problems can obviously motivate any assault. What distinguishes partner violence against women is that immediate stimuli converge in a singular consequence—female subordination. Regardless of whether a man beats his wife when he is drunk, stalks his girlfriend out of jealousy, or sets fire to his partner’s house when he is depressed, the selection of women as objects of coercion and control gives these events a single social meaning. Mediated through structures of inequality and read back into the proximate causes and diverse means employed in domestic violence, this meaning shapes the event into patterned behavior and gives it dimension, prevalence, and a history. The seeming paradox—that behavior violating basic canons of law, liberty, and decency remains widespread despite the presentation of its consequences to the systems charged with health and protection—marks the event as purposeful social behavior that can be explained (or resolved) only in the social realm (Schechter, 1978).

This chapter looks at battering through the prism of women’s encounters with the medical system, an important and unexamined realm of their help seeking. Three issues guide our inquiry. The first involves an empirical challenge to estimate the prevalence of domestic violence in the medical complex and distinguish its clinical sequelae. The second is to explain the emergence of the identified clinical profile, what we call the battering syndrome. A correlative task entails analyzing the contribution of the medical response (and, by extension, the other “helping” services) to this syndrome. The third issue is to explain why a population of otherwise normal women develop the profile of battering after they are assaulted. This entails showing how the implicit support medical intervention gives violent men plays into the overall constitution of patriarchal authority. At each step, we try to decipher the political in the personal, that is, to show how women’s struggle to affirm and men’s struggle to deny their liberty become embedded, through battering, in their personal problems.

Part I reviews the complete medical histories of women who sought assistance with injury from an urban emergency service. Using an index of suspicion, we determined how many women are at risk for abuse in the emergency population and compared this to the number actually recognized as such. The remarkable number of injuries attributable to domestic violence and the distinctive pattern of medical and psychosocial problems that accompany the adult trauma history reflect the diminishing realm of options available to women as they become entrapped in battering relationships. Our research tool tells us little about why physicians misread so many cases or why, despite this misreading, they respond in ways that actually aggravate the predicament of the (largely unidentified) population of battered women.

Cicourel (1964) argues that to understand official data fully, one must gauge its meaning to its recorders and to the system that generates it. Part II reviews women’s medical charts archaeologically, as social products that can tell us about how medical culture depicts the universe. This examination reveals how the medical system’s need to manage a persistent patient population fosters an implicit alliance with violent men. Ironically, the medical system thrives as numerous acts of failed treatment reproduce, and even strengthen, the invidious sexual contradictions that ensure a constant flow of female problems. Regardless of why a given clinician grasps for pseudopsychiatric labels when he or she confronts a clinical profile that defies classification within the individualist model of pathophysiology, this response increases the vulnerability of patients whose minority status makes them already vulnerable (Blum, 1978; Kelman, 1975). Critics have attributed medical insensitivity to women to the “commodification of health care” or, alternately, to dominance by an elite of male doctors (Berliner, 1975; Ehrenreich & English, 1979; Health Policy Advisory Center, 1970; Waitzkin & Waterman, 1974). In contrast, our focus is on how medicine as medicine—as a process of presumably scientific diagnosis, referral, and treatment—codetermines traditional sex hierarchies and contributes, even when individual health providers intend otherwise, to the suppression of struggles to overcome these hierarchies.

Part III critically reviews current theoretical perspectives on battering and proposes an alternative conceptualization. The review uncovers a host of contradictory findings and theories, both within disciplines and depending on whether analyses target psychological, interpersonal, cultural, or economic dimensions of the problem. Despite their differences, most researchers share the premises that domestic violence reveals male power, that violent families constitute a deviant subtype, and that battered women generally fail to act on their own behalf. In contrast, we argue that woman battering reflects the erosion of male authority, that domestic violence stands on a continuum with normative forms of male domination, and that woman battering grows out of women’s struggles to overcome their contradictory status, not from their compliance with or dependence on men. For instance, we interpret the oft-rejected survey reports that women use physical violence in conflict situations as often as men (Straus, 1977–1978) to argue that battered women are aggressive rather than helpless, passive, masochistic, or otherwise “sick.” The seeming paradox remains: Only women who are assaulted by partners suffer the battering syndrome. This, we believe, is because partner violence by men (but not by women) is socially reinforced at every level of women’s experience.

In the concluding sections, we analyze the contribution of the helping services to woman battering in terms of their historical role in mediating larger conflicts between a capitalist economy (which seeks to level all invidious distinctions) and the patriarchy (which seeks to maintain sexual hierarchy). Again in contrast to current thinking, we argue that the emergence of woman battering as a major expression of male control signals the nadir rather than zenith of male power. The erosion of male authority in the home is reflected empirically in the declining importance of the father-husband in working- and middle-class families, the relative decline in male-run family businesses, the socialization of domestic work in public and private services, and the increasing share of total income commanded by women. It is this decline, we believe, that explains why male power in the home must now be sustained by chronic—and increasingly explicit—outside intervention along a broad social front. The very transparency of such support and the desperate nature of violence and coercion in millions of relationships suggest that the larger contradictions excited by changes in the sexual status quo cannot be suppressed for long.

Women’s economic contribution has always been a key focus of male control. Even so, and regardless of how unfairly this work is distributed, the family’s major responsibilities, the early socialization of children and the formation of personality, are labors of love and never reducible to economic principles. Indeed, several historians have argued that the distortion of role assignments in the 19th century stimulated an autonomous “women’s sphere,” an extended community of intimates in marked contrast to the emerging capitalist world, where social connectedness among men appeared mainly in fetishistic forms (Cott, 1977; Sklar, 1976; Smith-Rosenberg, 1975). In demanding that women’s domestic work be socialized in a range of public services to which women flocked for employment, this community tore the veil from the imagery that linked women’s biological and cultural identities and made it possible to reconceptualize the family as a space free of exploitation, part of an extended community of love between equal subjects, the ideal to which many abused women cling. It is against this unfolding possibility that the use of violence and coercion to defend traditional hierarchies must be understood.

The disappearance of the family’s traditional economic and social roles—the decline of the patriarchy as a specific familial form—contrasts markedly with the subjective and objective extension of male domination throughout every aspect of life in the United States. Thus, although the classic patriarchy is dead, we argue that the social services, broadly construed to include education, religion, and recreation as well as medicine, law, criminal justice, and welfare, function today as a reconstituted or extended patriarchy, reinforcing female subordination by any means necessary, including violence.

Neither privacy nor personal life nor social connectedness remain in the millions of homes in which women are repeatedly beaten. For this reason, the violent family provides a point of departure, what might be termed a boundary case, to see how the male-dominated family is reproduced in the final instance, when one adult member tries to escape.

The Study: Abuse in a Medical Setting

Emergency medical services in the United States are oriented toward high-technology interventions in extreme trauma and illness. To the poor, minorities, and large segments of the white working class, however, emergency medical services are the only available source of basic medical care (Skinner & German, 1978). This conflict in how scarce health resources should be used is reflected in the tendency for emergency physicians to view minor, chronic, or social ills as inappropriate causes for them to intervene and to fragment complex social ailments diagnostically into isolated and relatively treatable symptoms. This pattern is disclosed in Kempe et al.’s (1962) work on child abuse. Rather than acknowledge familial assault as the etiology of children’s medical problems, physicians perform extensive medical workups in search of obscure blood and metabolic disorders that explain an accumulating history of multiple bruises and fractures.

Abused women who hesitate to call police or social workers for help will use medical services when they are injured (Schulman, 1979). Our study was designed to provide a preliminary estimate of the prevalence and dimensions of domestic violence in a medical population among whom the problem was considered trivial or nonexistent. An additional goal was to evaluate medicine’s response to these women. Because domestic violence was not a diagnostic category when the research began and because of dramatic findings resulting from Kempe et al.’s (1962) skeptical reading of medical data on children’s injuries, we developed an index of suspicion to identify abuse retrospectively from women’s adult trauma histories. Designated instances of domestic violence were obviously counted. In addition, we hypothesized that assaults or injuries with no known cause might result from abuse (probables). So might incidents where the recorded etiology contrasted markedly with the injury pattern described (e.g., bilateral facial contusions from “walking into a door”), that is, suggestives.1 The use of the index to identify at-risk women based on probable and suggestive injuries as well as positive episodes was validated by identifying similarly suspicious injury episodes among positive women, by finding that the frequency and pattern of injury among positives, probables, and suggestives was markedly different than the pattern among those classified as nonbattered (negatives), and by differentiating the clinical profile of battered from nonbattered women.

METHODS

The study population consisted of 520 women who sought aid for injuries at a major urban emergency room during 1 month. The full medical records were successfully retrieved for 481 of these women (92.5%), and previous emergency visits, hospitalizations, clinic records, and social and psychiatric service notes were analyzed. Each episode of injury was examined—some 1,419 trauma events ranging in frequency from 1 to more than 20 per patient—and the women were subsequently classified according to the following criteria:

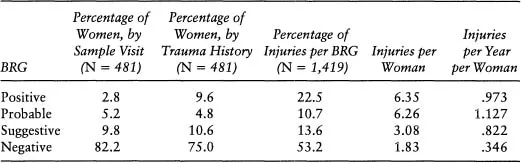

TABLE 1.1 Description of Battering Risk Groups (BRG)

- Positive: At least one injury was recorded as inflicted by a husband, boyfriend, or other male intimate.

- Probable: At least one injury resulted from a “punch,” “hit,” “kick,” “shot,” or similar action and deliberate assault by another person, but the relationship of assailant to victim was not recorded.

- Suggestive: At least one injury was inadequately explained by the recorded medical history.

- Reasonable negative: Each injury in the medical record was adequately explained by the recorded etiology, including those recorded as sustained in “muggings” or “anonymous assaults.”

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

Prevalence and Frequency

During the sample month, physicians identified 14 battered women (2.8%), although an additional 72 women (15%) had injuries we classified as probable or suggestive. Based on full trauma histories, however, 9.6% of the 481 women were positively identified as having been assaulted by a partner at least once and an additional 15.4% had trauma histories strongly indicative of abuse (Table 1.1, columns 1 and 2). Thus, based on trauma histories, one woman in four in this emergency population could be identified as battered, roughly nine times the number identified based on current visit reports.

The geographic location of the emergency service in a low-income and largely minority community skews outpatient use, making any generalizations about race, income, and domestic violence suspect (Zonana & Henisz, 1973). It is noteworthy, however, that white and minority women and welfare and medically insured women were significantly represented in the battered subset of this sample.

Of the more than 1,400 injuries these women had ever brought to this hospital, 75 (5%) were positively identified as abusive incidents based on physician records of a partner assault. An additional 340 (24%) fell into the probable or suggestive categories of this methodology. Thus, 30% of injuries presented by this cohort appeared to be directly associated with abuse. Importantly, almost half of the probable and a quarter of the suggestive incidents occurred to women who also evidenced positive abusive episodes, strongly supporting the methodology and indicating that only a tendency to disaggregate social ailments into discrete episodes prevented the appearance of battering as an ongoing process of repeated assault. Of all injuries ever presented by the 481 women to the hospital, almost half (46.8%) were presented by victims of domestic violence (Table 1.1, column 3).

The finding that women in the positive battering risk group had three times as many injury visits as nonbattered women (6.35 injury visits as compared with 1.83 injury visits) supports the hypothesis that injury is an ongoing fact of life for abused women. Women in the probable risk group had almost identical trauma histories as women in the positive risk group, again validating the identification method. Women in the suggestive risk group were injured at the same rate as positives and probables (.82 compared with 1.127 and .97 incidents per year) but had accumulated only half as many injury episodes (Table 1.1, columns 4 and 5), suggesting their abuse was of more recent onset.

Whereas physicians saw 1 of 35 of their patients as battered, a more accurate approximation is 1 in 4; whereas they traced 1 presenting injury in 20 to partner assault, the actual figure approached 1 in 3 (30%). Injury is an extreme consequence of assault and is reported infrequently. Thus, its institutional prevalence comprises only a small proportion of the true prevalence of domestic violence in the patient population. What clinicians officially portrayed as a rare occurrence was, in all likelihood, the single major cause of women’s injuries.

Duration

The duration of women’s abuse was determined by comparing the women who had ever been abused (25% of the sample) with those presenting at-risk injuries during the study month (18%). This showed that 72% of the abused women must still be considered at risk. A higher estimate is probably more accurate. Comparing the overall prevalence (25%) with the incidence of at-risk episodes during the past 5 years (23%) suggests that domestic violence ended in just 8% of the cases. As many as 92% of the women who have ever been in an abusive relationship in this population are still at risk, though it is impossible to tell whether the p...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Theoretical Perspectives

- Part II: Health Consequences

- Part III: Clinical Interventions

- References

- Name Index

- Subject Index

- About the Authors