![]()

1

Harm Reduction: History, Definition, and Practice

Diane Riley

Pat O’Hare

First, do no harm.

—Hippocrates

THE NATURE AND ORIGINS OF HARM REDUCTION

Harm reduction is a relatively new social policy with respect to drugs that has gained popularity in recent years—especially in Australia, Britain, and the Netherlands—as a response to the spread of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) among injection drug users. This chapter provides an overview of the origins, background, and nature of harm reduction and some detailed examples of harm reduction as it is being practiced around the world.

Although harm reduction can be used as a framework for all drugs, including alcohol, it has primarily been applied to injection drug use (IDU) because of the pressing nature of the harm associated with this activity. The main focus of this chapter is the reduction of injection drug-related harm, although brief mention is made of alcohol and other noninjection drugs. Barriers to the adoption of harm reduction, as well as its limitations, are also discussed.

Harm reduction has as its first priority a decrease in the negative consequences of drug use. This approach can be contrasted with abstentionism, the dominant policy in North America, which emphasizes a decrease in the prevalence of drug use. According to a harm reduction approach, a strategy that is aimed exclusively at decreasing the prevalence of drug use may only increase various drug-related harms, and so the two approaches have different emphases. Harm reduction tries to reduce problems associated with drug use and recognizes that abstinence may be neither a realistic nor a desirable goal for some, especially in the short term. This is not to say that harm reduction and abstinence are mutually exclusive but only that abstinence is not the only acceptable or important goal. Harm reduction involves setting up a hierarchy of goals, with the more immediate and realistic ones to be achieved in steps on the way to risk-free use or, if appropriate, abstinence; consequently, it is an approach that is characterized by pragmatism.

Harm reduction has received impetus over the past decade because of the spread of AIDS: Drug use is one of the risk behaviors most frequently associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV, or the virus thought to be necessary for AIDS). In some areas, IDU has become the main route of drug administration, and globally, it is now one of the primary risk factors for HIV infection. For example, in the United States, more than 20% of reported AIDS cases are directly associated with a history of injecting, and more than 30% of new HIV infections are in injection drug users. In some areas of Europe, injection of drugs accounts for as many as 60% of AIDS cases. What is more significant still is the rate at which HIV can spread among injection drug users. In cities such as Barcelona, Edinburgh, Milan, and New York, between 50% and 60% of drug users have become infected. In Thailand, where less than 1 % of users were infected in January 1988, more than 40% were positive by September of that year, with a monthly incidence rate of 4% (Rana, 1996). Less than a decade later in the northeastern province of Chiang Rai, one in six male military recruits and one in eight pregnant women were infected with HIV (Rana, 1996).

In all countries, HIV infection is not just a concern for the drug users themselves but also for their sexual partners. A number of studies in the United States and the United Kingdom have shown that between 60% and 100% of hetero-sexually acquired HIV is related to IDU, and that at least 40% of IDUs are in relationships with nonusers (Drucker, 1986; Rhodes, Myers, Bueno, Millson, & Hunter, 1998). Because of sexual spreading from injection drug-using partners, and because approximately one third of IDUs are female, vertical spreading to newborn children occurs. The possibility of transmission to the noninjecting community is increased by the fact that prostitution is sometimes used as a means of obtaining money for drugs, and many prostitutes are regular or occasional injectors. In addition, IDUs are a potential source of perinatal transmission: More than 50% of all pediatric AIDS cases in the United States are associated with injection drug use by one or both parents.

AIDS has thus been a catalyst for the rise in popularity of harm reduction. Before the AIDS pandemic, drug use was associated with a relatively low mortality rate because of periods of abstinence and natural recovery (Brettle, 1991; Wille, 1983). During the 1980s, there was a rapid increase in both AIDS- and non-AIDS-related deaths in drug users (Stroneburner et al., 1989). Brettle (1991) has suggested that “this increase in mortality for drug users is the driving force behind harm reduction and the reason we can no longer rely on spontaneous recovery for drug users” (p. 125). This is no doubt a correct assessment of the primary force behind harm reduction, but it is by no means a full account of it. In North America in particular, harm reduction attracted attention because of the effects of drug prohibition other than the spread of AIDS alone. The violent crime, gang warfare, prison overcrowding, and police corruption associated with prohibition have reached a level such that policymakers, practitioners, and members of the public alike are seeking alternatives to prohibitionist drug policy.

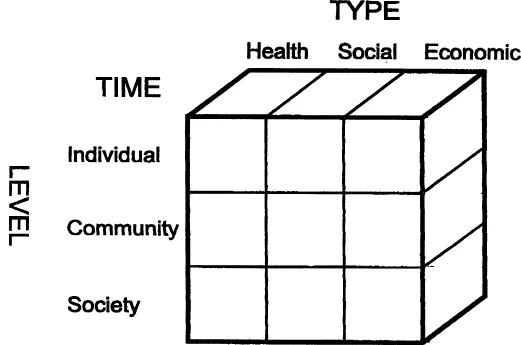

It has been claimed that attempts to legislate and enforce abstinence are counterproductive, and that there are harms due to these measures that are far worse than the effects of the drugs themselves (Erickson, 1992; Nadelmann, 1993; O’Hare, 1992; Riley & Oscapella, 1997). The harm reduction approach attempts to identify, measure, and minimize the adverse consequences of drug use at a number of levels, not just that of society as a whole. In a harm reduction framework, the term risk is used to describe the probability of drug-taking behavior resulting in any of a number of consequences (Newcombe, 1992). The terms harm and benefit are used to describe whether a particular consequence is viewed as positive or negative. In most cases, drug-taking behaviors result in several kinds of effects: beneficial, neutral, and harmful. The consequences of drug use can be conceptualized as being of three main types: health (physical and psychological), social, and economic. These consequences can be said to occur at three levels: individual; community (family, friends, colleagues, etc.); and societal (the structures and functions of society) (see Figure 1.1). They can also be broken down with respect to the time of their occurrence, into short-term and long-term effects. It is clear, given the wide range of moral and political views on the subject, that some consequences of drug use will remain highly controversial, and that assigning a positive or negative value will be purely subjective. Nevertheless, the harm reduction framework can be used as a means of better objectifying the evaluation process with respect to both drug programs and policies by allowing for the identification of harms that are to be dealt with.

The roots of harm reduction are in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and North America (Riley, 1993, 1994). Merseyside became a center for harm reduction policy because, like many other areas of the United Kingdom, it witnessed an epidemic spread of drug use, particularly heroin, in the early 1980s. Three important factors led to the establishment of the Mersey model of harm reduction. The first was the policy of the local drug dependency clinic, which was based on the old British system. Merseyside’s major city, Liverpool, did not have its own drug dependency clinic until the mid-1980s. Prior to this, outpatient drug treatment was limited to a few psychiatrists who, in contrast to doctors in most other parts of the country, did not completely abandon the old British system. The British system emerged as a response to the recommendations of the Rolleston Committee, a group of leading physicians, on treatment of drug abusers in England during the 1920s. One of the most significant conclusions of the committee was that in certain cases, maintenance on drugs may be necessary for the patient to lead a useful life. To this day, injectable opiates have continued to be prescribed on a take-home basis in Merseyside.

Figure 1.1. Classification of the Consequences of Drug Use

A second factor in the emergence of the Mersey model was that in 1986, the Mersey Regional Drug Training and Information Centre began one of the first syringe exchange schemes in the United Kingdom, with the aim of increasing the availability of sterile injecting equipment to drug users in the area. The third factor was the cooperation of the local police, who agreed not to place drug services under observation and began to refer to drug services those drug users who had been arrested, a policy known as “cautioning.”

In Merseyside, the harm reduction services include needle exchange; counseling; prescription of drugs, including heroin; and employment and housing services. One of the reasons that the Merseyside approach has proven so effective is that many levels of service and a wide variety of agencies are involved. The services for the drug user are integrated so that they can obtain help more readily when they need it. Together, Mersey Authority and the Merseyside Police have devised a comprehensive and effective harm reduction strategy, which came to be known as the “Mersey Model” of harm reduction (O’Hare, 1992).

All of the available evidence on HIV infection among IDUs in Merseyside suggests that the Mersey HIV prevention strategy for IDUs is very effective (see Stimson, 1997, for a review of approaches to HIV among drug users in the United Kingdom). Contacts with drug users have increased steadily over the past 5 years, and anecdotal evidence suggests that the number of drug-related health problems seen by services has dropped. Self-reported sharing of injecting equipment has declined, indicating positive behavioral change. By the end of 1994, only 29 drug injectors were known to be HIV positive and resident in the region. Official statistics indicate a decrease in drug-related acquisitive crime in many parts of the region, whereas the national rate is increasing (HIT, 1996). It is thought that the low prevalence of crime and HIV infection can be related to the various policies for dealing with drug use in the area.

In the early 1980s, Amsterdam recognized that drug use is a complex, recurring behavior, and that reduction of harm means providing medical and social care while waiting for natural recovery in order to avoid some of the more harmful consequences of injection drug use (Buning, 1990). Needle exchange began in 1984 after the Junkie Union advocated and then initiated the first exchange in order to prevent the spread of hepatitis B among users (Buning et al., 1986; Buning, van Brussel, & van Santen, 1988). Amsterdam has taken a pragmatic and nonmoralistic attitude toward drugs, and this has resulted in a multifaceted system that offers a variety of harm reduction programs. Police in the Netherlands focus attention and resources on drug traffickers, not users.

Although North America is not usually thought of in connection with harm reduction, Canada and the United States have been home to a very significant harm reduction strategy. One of the earliest forms of harm reduction for IDUs were methadone maintenance programs that began in Canada in the late 1950s and in the United States in the early 1960s. Methadone maintenance was seen as harm reduction for society, usually in terms of the reduction of crime or the reentry of drug users to the workforce (Brettle, 1991); improvement of the individual’s physical health or protection of their human rights was not a priority. The spread of AIDS in opiate users has changed the entry and evaluation criteria for methadone programs, and it has also highlighted the need to modify these programs in order to reduce individual as well as societal harms (Jürgens & Riley, 1997; Newman, 1987; Springer, 1990).

A number of countries and organizations have now adopted harm reduction as both policy and practice. For example, the British Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (1988) responded to the spread of HIV in IDUs by revising its policy on drug use to one of harm reduction: “We have no hesitation in concluding that the spread of HIV is a greater danger to individual and public health than drug misuse. Accordingly, services which aim to minimize HIV risk behaviour by all available means should take precedence in developmental plans” (para. 2.1). The World Health Organization (1986) has expressed a similar opinion, stating that policies aimed at reduction of drug use must not be allowed to compromise measures against the spread of AIDS.

The Nature of Harm Reduction

Features of Harm Reduction

The essence of harm reduction is embodied in the following statement: “If a person is not willing to give up his or her drug use, we should assist them in reducing harm to himself or herself and others” (Buning, 1993, p. 1). The main characteristics or principles of harm reduction are as follows:

Pragmatism. Harm reduction accepts that some use of mind-altering substances is inevitable, and that some level of drug use is normal in a society. It acknowledges that, although carrying risks, drug use also provides the user with benefits that must be taken into account if drug-using behavior is to be understood. From a community perspective, containment and amelioration of drug-related harms may be a more pragmatic or feasible option than efforts to eliminate drug use entirely.

Humanistic values. The drug user’s decision to use drugs is accepted as fact, as his or her choice; no moralistic judgment is made to either condemn or support the use of drugs, regardless of level of use or mode of intake. The dignity and rights of the drug user are respected.

Focus on harms. The fact or extent of a person’s drug use per se is of secondary importance to the risk of harms consequent to use. The harms addressed can be related to health, social, economic, or a multitude of other factors, affecting the individual, the community, and society as a whole. Therefore, the first priority is to decrease the negative consequences of drug use to the user and to others, as opposed to focusing on decreasing the drug use itself. Harm reduction neither excludes nor presumes the long-term treatment goal of abstinence. In some cases, reduction of level of use may be one of the most effective forms of harm reduction. In others, alteration to the mode of use may be more effective.

Balancing costs and benefits. Some pragmatic process of identifying, measuring, and assessing the relative importance of drug-related problems, their associated harms, and costs/benefits of intervention is carried out in order to focus resources on priority issues. The framework of analysis extends beyond the immediate interests of users to include broader community and societal interests. Because of this “rational” approach, harm reduction approaches theoretically lend themselves to systematic evaluation to measure their impact on the reduction of harms in both the short and the long term, thereby determining whether their cost is warranted compared to some other, or no, intervention. In practice, however, such evaluations are complicated because of the number of variables to be examined in both the short and long term.

Hierarchy of goals. Most harm reduction programs have a hierarchy of goals, with the immediate focus on proactively engaging individuals, target groups, and communities to address their most pressing needs. Achieving the most immediate and realistic goals is usually viewed as the first step toward risk-free use, or, if appropriate, abstinence (e.g., see the guidelines from the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs).

Definition

At present, there is no agreement in the addictions literature or among practitioners as to the definition of harm reduction. One working definition is the following: “an attempt to ameliorate the adverse health, social or economic consequences of mood-altering substances without necessarily requiring a reduction in the consumption of these substances” (Heather, Wodak, Nadelmann, & O’Hare, 1993, p. vi).

In the literature, the term harm reduction is often used interchangeably with the lesser-used term harm minimization. Two additional terms that are frequently used synonymously with harm reduction are risk reduction...