![]()

PART I

Introduction

![]()

CHAPTER 1

A Model for Understanding University Teaching and Learning

JAMES E. GROCCIA

“There is nothing more practical than a good theory.”

Kurt Lewin (1952, p. 169)

The use of theories, metaphors, simulations, and models has been commonplace in higher education, especially in science-based disciplines, to comprehend the incomprehensible, to explain the unexplainable, or to view a picture of the unviewable. Complex issues can be made less complex and simple issues can be made complex through the use of an analog representation (model) that enables researchers or practitioners to develop intervention strategies or solve problems. It appears to me that one way to develop approaches to improve the teaching and learning in higher education is to develop and use a model that illustrates the multiple variables that fall under the term college teaching.

What Are Models?

In a general sense, a model is a simplified representation of a system that concentrates attention on specific aspects of the system (Ingham & Gilbert, 1991). A model allows aspects of the system (i.e., processes, structure, objects, events, ideas) that are complex or abstract to be rendered either visible or more easily understood (Gilbert, 1995; Gobert & Buckley, 2000). A model is an icon that embodies features from the original in a way that says, “This is how the original is” (Black, 1962, p. 221).

The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 2011) provides two definitions of a model that are relevant to this discussion: a copy of something, usually smaller than the original object, and a simple description of a system used for explaining how something works or calculating what might happen. Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus (1998) define a model as a formal framework for representing the basic features of a complex system by a few central relationships. Models can take the form of graphs, mathematical equations, and computer programs. David Begg, Stanley Fischer, and Rudiger Dornbusch (2000) indicate that a model or theory makes a series of simplifications from which it deduces how people will behave. It is a deliberate simplification of reality. Scientists and mathematicians use their models in problem-solving and problem-analyzing processes, and economists use models in economics to analyze and visualize economic problems (Kaewsuwan, 2002).

Characteristics of Good Models

Others have attempted to identify the characteristics of a “good” theory (Huberman & Miles, 1994; Popper, 1963; Swan, 1994; Ur, 2001), but I have been unable to find a list of the characteristics of a “good” model. Therefore, I will extrapolate from the characteristics of the former presented by Penny Ur (2001) to describe those of the latter:

- Plausibility: The model appears to be in accordance with experience and data. The model is truthful to what we know, as limited as that knowledge may be; it is true as far as we can assess from rational observation and experience.

- Simplicity: The model presents a representation or explanation that avoids complications and is as simple as possible. A good model is elegant in that it expresses its meaning with the least amount of words, figures, or ideas possible.

- Explicitness: The model is presented and stated in clear and understandable terms. It is easily communicated to others so that it can be used by others to extend knowledge and application.

- Comprehensiveness: A good model encompasses all of the data and variables necessary for understanding an application.

- Limited: The model includes what is necessary and clearly indicates where or to what it does and does not apply. The boundaries and demarcations of the model are clear.

- Usefulness: The model clearly explains what is going on so that it can generate, explain, or predict present and future action. A good model is useful and practical.

- Testable: The model presents ideas that can be tested, verified, or rejected.

- Aesthetic appeal: The model is visually, verbally, and graphically clear and elegant. A good model is not cluttered with unnecessary images or words and is visually attractive or stated in a compelling metaphor (Ellis, 1997).

Why Use a Model to Understand Teaching and Learning?

Models are communication tools to summarize, generalize, or transmit understanding to help make a complex process or concept more easily comprehended. Models inform practice. Models can lead to the building of theories, which in turn can lead to creation of hypotheses that lead to testing, intervention, and change. In the case of teaching and learning, a model can create a holistic conceptualization of teaching and learning to provide a framework for research and understanding to assist improvement efforts. A model illustrates the connections and interconnections between variables of interest. A model of teaching and learning helps the teacher and educational researcher understand the interplay between variables and their interdependence. Such awareness can provide multiple points of intervention as change in one element or variable in the model can stimulate change in others. This systemic approach can maximize efforts to improve teaching and learning and empower teachers in teaching improvement efforts.

A model also visually highlights the complexity of what is being modeled. A model of college teaching and learning says to teachers that there is more to teaching than what one does in front of students. Understanding the dynamic nature of the instructional process, and ways to improve it, requires knowledge about issues that take place before, during, and after the information-sharing process.

Understanding the complexity of teaching and learning can help avoid a “techquie” approach to teaching improvement. By this I mean the all too often attempt to improve teaching by the imitation or adoption of a teaching technique (e.g., “clickers,” problem-based learning, cooperative learning, jigsaw teaching) without a full understanding of the pedagogical reasons for the use of such a technique, or of its impact on other variables in the teaching and learning process.

Precursor Models of Teaching and Learning

The Transmission Model of Teaching and Learning

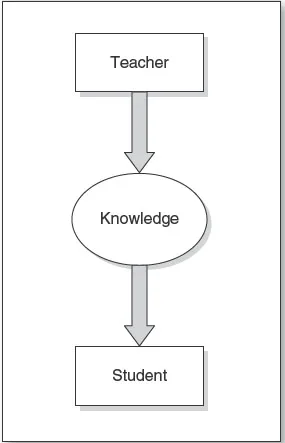

Based on the prevalent form of instruction in the majority of higher education classrooms around the world, the lecture, one would assume that teaching and learning is a simple process. The teacher’s (the expert) job is to transfer knowledge through talking to students (the novice) whose role is to receive knowledge through listening, watching, and maybe taking notes. The professor’s job is to profess and the students’ job is to receive, interpret, and internalize the “professtations”—the professor’s words and actions. This top-down transition model of teaching “has prevailed throughout fundamental innovations including writing, books, computers, and the Internet.” (Laurillard, n.d., p. 1). The transmission model can be called the default conceptualization of teaching and is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

This default model is fraught with difficulties, the most significant of which is its very simplicity. Such a conceptualization ignores the complexity of the teaching-learning process and the importance and interplay of many influential variables. Having a comprehensive model from which to view teaching and learning can guide individual faculty members in the design of teaching and learning actions and environments and guide educational developers in selecting and presenting the content for instructor training programs.

Figure 1.1 The Transmission Model of Teaching

Lowman’s Two-Dimensional Conceptualization of Effective College Teaching

Joseph Lowman’s (1995) model was developed as a result of his research analyzing the adjectives used to describe excellent teachers in letters submitted for the chancellor’s teaching awards at the University of North Carolina. Lowman’s factor analysis of student evaluations of teaching performance yielded two factors, teaching technique and rapport, as the most critical variables in effective teaching (see Table 1.1). Lowman identified a two-dimensional model of exemplary teaching that focused on intellectual excitement created by instructor clarity in the classroom, and interpersonal rapport and relationship building with students. This model can be characterized as teacher-centered and performance-based, and it does not focus on pre-instruction behaviors or the influence of the instructional setting. Classroom dynamics, such as student and teacher attitudes and class moral and some psychological issues of teachers and students are mentioned (i.e., sources of satisfaction and dissatisfaction, communication styles, interpersonal interaction between teachers and students, affective and classroom control measures) but Lowman’s focus is primarily on the teaching skills of instructors.

Table 1.1 Lowman’s Two-Dimensional Model of Effective College Teaching

Dimension 1: Intellectual Excitement- Clarity of presentations (what is presented)

- Emotional impact on students (way material is presented)

|

Dimension 2: Interpersonal Rapport- Awareness of interpersonal nature of the classroom

- Communication skills that enhance motivation and enjoyment of learning and that foster independent learning

|

Teaching-Learning Transactional Model of College Teaching

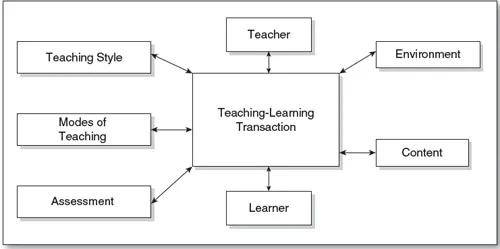

David Dees and colleagues (2007) developed their transactional model to provide a framework to guide college teacher reflection “before, in-the-moment, and after the event, that recognizes the complexity of the act of teaching, is sensitive to the aesthetic dimensions of both teaching and reflection, and provides a context to examine tacit decisions made during the act of teaching.” (p. 130). The model is a qualitative description of the key elements of teaching to bring them out in the open to encourage reflection, discussion, and holistic inquiry. The transactional aspect of Dees et al.’s model (see Figure 1.2) illustrates the connected back and forth aspect of the various instructional elements.

Figure 1.2 Teaching-Learning Transactional Model of College Teaching (modified from Dees et al., 2007, p. 132)

A Model for the Study of Classroom Teaching

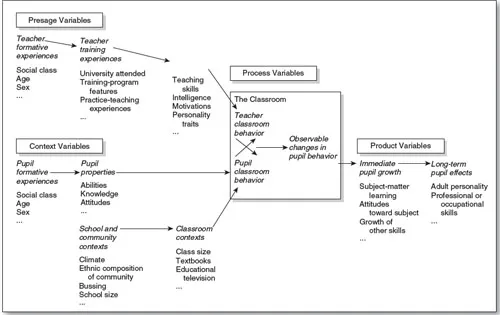

Michael Dunkin and Bruce Biddle (1974), based on an earlier formulation by Harold Mitzel (1960), proposed a four-variable model to help educational researchers better understand the complex aspects of classroom instruction (see Figure 1.3). Developed primarily to assist researchers to organize findings of research on teaching, this model illustrated the complexity and interconnectedness of college teaching. Dunkin and Biddle’s model contains four classes of variables for study: presage (teacher characteristics, experiences, training), context (properties of pupils, schools, community, classroom), process (teacher and student actions), and product (immediate and long-term effects). Each rectangle in the model represents a region of variables deserving of research, and the arrows presume a causative relationship between regions and are sources of hypotheses for future research. This model had “an enormous impact” (Shulman, 1986, p. 6) on the field of educational research by providing a theoretical framework and vocabulary for those studying teaching and learning.

Figure 1.3 A Model for the Study of Classroom Teaching (from Dunkin, The Study of Teaching, 1E. © 1974 Wadsworth, a part of Cengage Learning, Inc. Reproduced by permission. www.cengage.com/permissions)

Groccia’s Model for Understanding Teaching and Learning

I have developed a model for understanding university teaching and learning that share many of the components presented in the previous models. The model was initially described in a newsletter published at the University of Missouri (Groccia, 199...