![]()

1

Introduction to RTI and the Case Study Model

Response to intervention (RTI) is a school-based system designed to identify and meet children’s needs through increasingly more focused and intensive levels (“tiers”) of assessment and intervention. It can be applied to academic, behavioral, and mental health issues. A key principle underlying RTI is the notion that all efforts to evaluate and resolve children’s school performance deficits represent “problem solving,” and that such efforts should persist until effective solutions are found. Stanley Deno (2002) defines a problem as a difference between what is (i.e., the child’s low score on a measure of math skill), and what is expected (i.e., a score similar to that of the average student, or to a benchmark standard). RTI is a large-scale problem-solving process, which incorporates assessment to identify children who demonstrate deficits, and it provides intervention to reduce or eliminate the deficits.

Assessment in RTI is used in a preventive context, to ensure that universal instruction is effective, and to identify students who demonstrate risk for failure. At each successive level, assessment becomes more focused on conditions associated with poor school performance. Decisions (i.e., about the need for intervention, characteristics of appropriate interventions, and effectiveness of interventions) are based not on the judgments or opinions of teachers and other instructional personnel but on data generated in the course of assessment, as well as on the strength of evidence supporting the choice of a particular intervention strategy.

In a remedial context, RTI is used to gather information needed to select appropriate interventions and to monitor their effects. Intervention in RTI consists of scientific, research-based strategies to remediate deficient performance, provided on a classroom, group, or individual basis. Increasingly more intensive and specialized forms of intervention are introduced as children demonstrate failure to respond adequately to interventions provided at each successive level. At the most intensive level (Tier 3), the selection of an appropriate and effective intervention requires in-depth study of factors contributing to or maintaining the child’s performance deficit. This process—along with procedures to monitor and judge the success of interventions—is implemented in the form of a case study.

CONTEXT AND HISTORY

Although relatively new to the field of school psychology, the conceptual and practical foundations of the RTI model are not new. In the field of special education, attention has long been paid to the need to track children’s academic progress and to apply evidence-based interventions to their learning problems (Deno & Mirkin, 1977; Ysseldyke & Algozzine, 1982). In recent years, the shift in attention from procedural accountability (i.e., are schools following the rules?) to accountability for student outcomes (i.e., are students learning?) has created an ideal environment for RTI, with its emphasis on routine and systematic assessment of student performance. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), reauthorized in 2001 as the No Child Left Behind Act (2002), mandated the attainment of satisfactory levels of academic skills by all children, lending a sense of urgency to efforts to improve instruction and intervention for underperforming students.

In the mid-1970s, the behavioral consultation (BC) model was introduced as a method for defining student performance problems, identifying contributing factors, developing interventions targeting those factors, and measuring the success of interventions (Kratochwill & Bergan, 1990) (See Table 1.1 for a summary of the stages of the BC model). Variations of the BC model have evolved over the years and have been adopted by most states in policies requiring intervention in general education, prior to consideration of special education eligibility (Buck, Polloway, Smith-Thomas, & Wilcox Cook, 2003).

Numerous studies support the effectiveness of BC and its procedural offspring for addressing children’s school performance problems (Burns & Symington, 2002). The emphasis of these approaches on the collection of data to describe student performance and measure intervention outcomes has been complemented by the growing popularity of assessment techniques such as Curriculum-Based Measurement (CBM), which directly measure children’s academic skills (Hosp, Hosp, & Howell, 2007). These developments provide technical support for RTI, with its dual emphasis on assessment and intervention as key elements of effective educational practice.

Table 1.1 The Four General Stages of Behavioral Consultation

- Problem identification (definition of the problem in measurable terms, including comparison with some standard or norm that defines “expected” performance)

- Problem analysis (study of the factors that are contributing to the problem; in functional assessment, this includes developing and testing hypotheses about environmental factors that are functionally related to the problem)

- Plan implementation (intervention carried out according to a plan that includes frequent measurement of the child’s progress during the intervention as well as monitoring of intervention fidelity)

- Problem evaluation (review and analysis of progress-monitoring results to determine whether the intervention should continue, change, terminate, or be phased out)

Source: Adapted from Bergan and Kratochwill (1990)

A third factor has contributed to the growing influence of the RTI approach: the poor “treatment validity” of so-called “test-and-place” practices, in which diagnostic evaluations often led to special education placement (where appropriate interventions were assumed to occur). Test-and-place practices have been criticized for their use of evaluation procedures that seek to identify deficits in individual aptitudes—often inferred from the results of individual intelligence tests. This, in turn, leads to recommendations for interventions to remediate those deficits (and, by further inference, the academic problems thought to result from aptitude deficiencies).

However, research support for this approach has been limited, and efforts to link test-and-place practices with meaningful and effective intervention have been largely unsuccessful (Reschly & Ysseldyke, 2002). In contrast, RTI employs direct measurement of academic performance and behavior, identifying relationships between problems and environmental factors through a process of hypothesis testing. When appropriate targets for intervention have been identified (e.g., opportunities for students to practice skills, incentives for accurate performance), strategies are devised to modify or create environmental conditions that will optimize the potential for improved student performance.

Finally, while the RTI model can be applied to a range of suspected disabilities, its growing popularity can be traced to concerns about unacceptably high rates of learning disability diagnosis and special education placement. This disability category accounts for just over 50% of children enrolled in special education programs (Vaughn & Fuchs, 2003). Federal government initiatives clearly conveyed concern about problems that were apparent in practices used to identify learning disabilities.

In December, 2003, the National Research Center on Learning Disabilities (NRCLD) (2004) held a symposium to explore alternatives for meeting the needs of children with specific learning disabilities. Created by the U.S. Department of Education (Office of Special Education Programs, OSEP), the NRCLD, a joint endeavor of Vanderbilt University and the University of Kansas, had been given the task of conducting research and helping schools learn about more effective service delivery models. Prior to this symposium, OSEP had sponsored the Learning Disabilities Summit: Building a Foundation for the Future in August, 2001, and commissioned a series of white papers and roundtable discussions on the topic (Bradley, Danielson, & Hallahan, 2002).

The Executive Summary of the 2003 NRCLD Symposium outlines the problems that led to the OSEP initiative:

the exponential increases in the number of students who are considered to have learning disabilities, the reliance on IQ tests, the exclusion of environmental factors, the inconsistency in procedures and criteria within school districts and across states, and the reliance on aptitude-achievement discrepancy formulas and the manner in which they are used.” (NRCLD, 2004, p. 1)

In addition to these concerns, Kavale and Forness (1999), reported results of a meta-analysis of research on special education suggesting that placement of children with disabilities in special education programs in itself often did not result in meaningful improvement, perhaps due in part to lower student performance expectations.

In the 2004 reauthorization of IDEA, legislators addressed these concerns by offering an alternative to traditional test-and-place practices. Specifically, the law allowed schools to “use a process that determines if the child responds to scientific, research-based intervention as part of the evaluation procedures” (Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 2004, P.L. No. 108-446, par 614). Commonly interpreted as a reference to RTI, this language suggests that the process of delivering interventions based on ongoing performance assessment can serve as a basis for determining whether a child has a specific learning disability. It shifts emphasis from a determination of disability based on results of diagnostic tests administered at one point in time to an examination of data resulting from the application of interventions over time.

In summary, a variety of factors has created an environment conducive to RTI implementation, including mandates for accountability, the evolution of behavioral consultation and related models for service delivery, the push for evaluation practices with greater “treatment validity,” and dissatisfaction with assessment and placement practices for children with specific learning disabilities.

THE RESPONSE TO INTERVENTION PROCESS

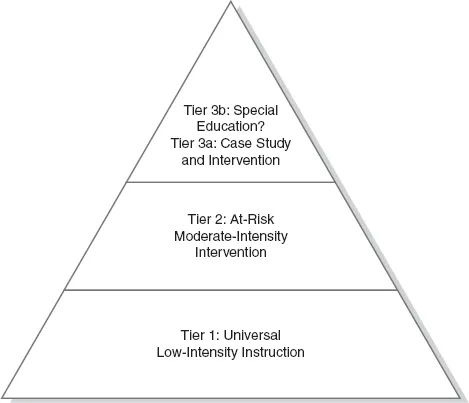

Assessment and intervention practices employed in the RTI model are typically described in context of three “tiers,” organized hierarchically to reflect increasingly more focused assessment and more intensive intervention (Figure 1.1).

Tier 1. Tier 1 is considered a form of “primary prevention,” in that it involves all children in high quality, research-based core instruction, as well as periodic assessment of performance. It is similar to the evidence-based practice of inoculating all children against disease or conducting periodic “well-child” exams to ensure satisfactory development. Tier 1 includes differentiated instruction (e.g., flexible grouping) and classroom accommodations (e.g., study aids) to enhance children’s understanding of core instruction. Universal screening at Tier 1 consists of quarterly assessment of key academic and behavioral targets or skills. Local norms can be generated from these assessment results and, along with benchmark standards, are used to evaluate students’ progress toward established goals. Tier 1 assessment also may include strategic monitoring of the performance of students who display moderate performance deficits and of emergent reading skills of students in the primary grades.

Figure 1.1 Response to Intervention “Pyramid”

Tier 2. When Tier 1 assessment identifies children who are not making adequate progress, the second level of the assessment and intervention process is activated. Tier 2, a form of “secondary prevention,” consists of “additional individual instruction, small group instruction, and/or technology-assisted instruction to support and reinforce skills taught by the classroom teacher” (McCook, 2006, p. 30) or interventions to reduce the occurrence of behavior problems among individuals known to be at risk. Tier 2 interventions are generally chosen from a set of research-based strategies selected by the school for remediation of targeted academic and behavior problems. They are considered to be of moderate intensity because they involve more resources than would be available to entire classes, but do not require the highly specialized resources and strategies that are delivered at Tier 3.

What kinds of intervention are used at Tier 2? In some cases, Tier 2 interventions—which are always offered in addition to the instruction of Tier 1—consist simply of additional time and opportunity for review and practice of skills, which can be provided by the general education teacher, a classroom aid, or even the student or the student’s classmate. Other Tier 2 interventions make use of ancillary personnel, such as federally funded reading and math tutors, who provide additional instruction for students having difficulty acquiring skills, or classroom aids who monitor and provide feedback and incentives for targeted behaviors. However, the mere assignment of a student to an existing remedial program does not guarantee that a valid, research-based intervention will be used at Tier 2. Instead, instructional practices and materials and behavior plans should be reviewed to ensure that they have research support and that the intervention strategies themselves are used in an appropriate and consistent manner.

Still other Tier 2 interventions are drawn from the “standard treatment protocols” developed by literacy experts, particularly for use with children in the primary grades. The “empirical approach” to problem solving also can be used; in it, general education teachers or teams select interventions from an array of strategies that research has shown to be effective for various types of problems, without testing their effectiveness for specific children (e.g., repeated readings or listening previewing for reading fluency problems, active teaching of classroom rules with incentives for compliance in the case of behavior problems).

Tier 3. The topmost area of the pyramid-shaped RTI model is reserved for those (relatively few) students who do not make adequate progress at Tier 2. The assumption underlying Tier 3 is that instruction and interventions delivered at Tiers 1 and 2 have not targeted the actual cause of the problem, so further assessment is needed. The case study model provides a framework for this assessment. It uses a planning process that takes into consideration children’s unique needs and circumstances, in contrast to Tiers 1 and 2, where standardized interventions are offered to children who demonstrate risk for failure.

Unlike Tiers 1 and 2, Tier 3 has not received much attention in discussions of the RTI model, probably because it is often considered to be equivalent to special education. In fact, The National Research Center on Learning Disabilities (2007) observes that, “in most schools, Tier 3 might be synonymous with special education,” although the author goes on to describe it as “sustained, intensive support in the specified area of need … tailored to the individual student … [which] may continue for much longer periods, depending on student need” (p. 7). The difficulty with equating Tier 3 with special education placement is that it does not allow for the conceptual framework of RTI as a problem-solving model to be incorporated into the third tier of the process. Although special education services and comprehensive evaluation to determine eligibility may occur at Tier 3, the tier is defined in more general terms as individual assessment and intervention to meet children’s unique and specific needs, without regard for the setting (special vs. general education) in which it occurs.

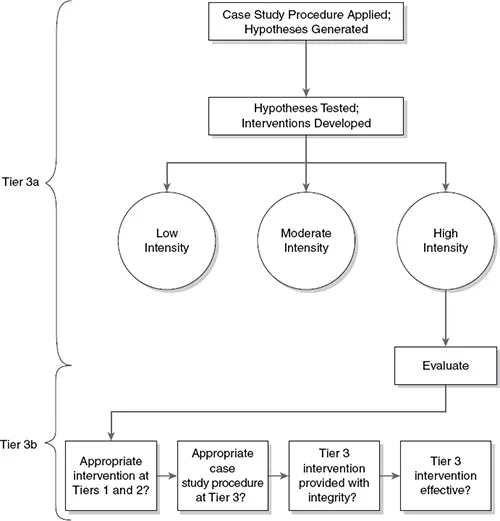

The case study procedure in this text presents Tier 3 in two phases (see Figure 1.2); Tier 3a consists of the application of the case study procedure to generate and test explanations (hypotheses) for the child’s performance problem. When a “high probability” hypothesis has been identified, interventions targeting factors implicated in that hypothesis can be developed and monitored to evaluate effectiveness. Interventions may vary in intensity, from low (e.g., additional practice opportunities in a peer-assisted learning context, based on a hypothesis of “insufficient practice”), to moderate (e.g., daily small group instruction to teach decoding or comprehension skills, based on a hypothesis of “insufficient help/instruction”), to high intensity (e.g., daily one-to-one instruction using curricular materials from a lower grade level). Children who require high-intensity interventions receive them in context of Tier 3 (often, but not always, on an individual basis), while those requiring less intensive intervention might be assigned to participate in intervention activities already in place for children at Tiers 1 and 2. When a high-intensity intervention is required, it may be of such a specialized nature that a disability is suspected, triggering an evaluation to determine whether entitlement to the intervention—in the form of an individual education plan—is warranted.

Figure 1.2 Tier 3 of the RTI Model

To determine whether a disability is present, interventions of high intensity should be evaluated (Tier 3b) across several criteria: First, whether appropriate, evidence-based interventions were provided as intended at Tiers 1 and 2; second, whether the case study procedure at Tier 3 was applied in an appropriate manner (i.e., with “fidelity”); third, whether the intervention resulting from the case study procedure was provided as intended (i.e., with “integrity”); and, fourth, whether progress-monitoring results indicate that the intervention was effective (successful or promising). These conditions all must be met before the question of eligibility for special education (i.e., legal entitlement to intervention using specialized resources, based on an individual education plan) should be considered. The decision-making process associated with special education eligibility determination is described in more detail in Chapter 9.

Although the focus of most of the literature is on academic performance pr...