- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Crime and Nature

About this book

Crime and Nature, written by the always innovative and original Marcus Felson, is the first text to provide students with a unique, new perspective for thinking about crime and how modern society can reduce crime?s ecosystem and limit its diversity.

Key Features

- Connects crime to its larger world: This innovative book shows how crime draws from the larger ecosystem, that is, how offenders hunt for targets and how they depend on one another. Extending crime ecology well beyond other works, this book shows how to help shut off crime opportunities and reduce crime in local areas. An examination of how people defend against crime is also provided.

- Stimulates critical thinking about crime: Crime feeds off of legal activities, both shady and legitimate. Through a wealth of examples, ranging from racketeering to juvenile street gangs, this book shows criminology students what to look for and how to sort it out. The author uses recent empirical studies to validate the principles presented and draws from a wealth of experience in other fields, always keeping an eye on what every criminologist needs to know.

- Presents intriguing, useful information in an engaging and unique style: Writing in a warm and personal voice, the author uses an engaging, student-friendly style to build a sophisticated view of crime in small, sure steps. Down-to-earth ideas and examples are presented through concise exhibits.

Intended Audience

This is an excellent supplementary text for a variety of undergraduate courses in criminology and criminal justice, including Criminological Theory, Crime Control and Prevention, Introduction to Criminology, Law and Society, and Social Problems. It will have a lasting impact on present and future criminologists.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Crime and Nature by Marcus Felson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

SAGE Publications, IncYear

2006Print ISBN

9780761929109, 9780761929093eBook ISBN

9781452236384PART I

Introduction

The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.

—Oscar Wilde1

Life is an offensive, directed against the repetitious mechanism of the Universe.

—Alfred North Whitehead2

I am interested in those things that repeat and repeat and repeat in the lives of the millions.

—Thornton Wilder3

Reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.

—Richard P. Feynman4

1

Crime and Life

Crime is a lively process. Offenders, victims, guardians against crime are active before, during, and after crimes occur. This chapter explains how crime fits the larger definition of life and draws upon naturalists to help us understand its liveliness. For example, Charles Darwin (1809–1882) watched hundreds of plants over 24-hour periods; he then wrote an entire book about their motions.5

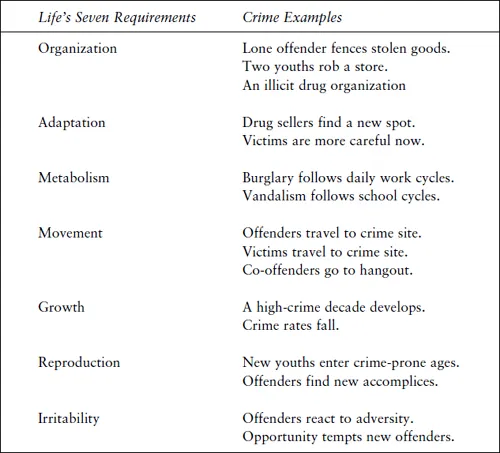

This book is about crime in motion, its living processes.6 Life has seven special requirements: organization, adaptation, metabolism, movement, growth, reproduction, and irritability.7 This book examines how crime meets these requirements, in the context of its larger environment (see Exhibit 1.1). This chapter introduces the seven concepts, with some initial examples of them.

Exhibit 1.1 Crime and the Seven Requirements of Life

That environment changes in ways that impinge greatly on crime. In the 19th century, manufacturers discovered combination locks that make safes more difficult to break into. Then a man named George Bliss, who liked to break into banks, got tired of struggling with these locks. He studied how the new locks worked and constructed a wire device called “the Little Joker.” It required him to break into each bank twice. During his first break-in, he would insert the Joker into the lock and leave it. The bankers did not know that his simple device was recording the numbers scratched most often. In his second burglary, he could see the combination etched into the wire, and open the safe quickly.8 In time, safe companies learned what to do to stop this, and safecracking virtually died out. You can easily see that crime and its prevention are dynamic aspects of a living world.

This is an interesting example, but our task is to put many examples together in order to understand how crime works in a larger world. That is a challenge to me as a theorist and to you as a student of crime. In wrestling with the facts of crime in the real world, I try to take Einstein’s suggestion for good science: “Things should be made as simple as possible, but not any simpler.”9

To apply that advice, we study how crime varies, but we also seek regularities to make sense of it all.

Organization and Living Crime

Like the rest of life, crime can be organized in many forms—primitive and elaborate, informal and formal, short term and long, small scale and large, single layer and multilevel. Fortunately, some crime experts are very attuned to organizational variety. Professor Peter Reuter of the University of Maryland has shown that illegal gambling and drugs display diverse forms of organization.10 For example, “numbers rackets” are rather dispersed illegal gambling operations, with central control largely impractical. On the other hand, dispersed illegal gambling operations often depend on centralized “banks” to fund their payouts to customers.

Professor David Friedrich of the University of Scranton has shown us a great organizational variety, too, in white-collar crimes.11 Some such crimes involve only one or two persons, while others develop elaborate conspiracies, even involving entire corporations. What seem to be the most “organized” criminal activities are usually not that fancy at all. Many drug sales networks are really sequences of simple illegal events, involving different persons rather than a simultaneous organization. As we shall see, crime is organized in the naturalist’s sense of that word, not necessarily the televised version. In later chapters, this book explains many of crime’s organizational forms in the context of larger ecology.

Adaptation and Living Crime

Human genes have produced a rather flexible species, able to live in heat and cold, dark and light, mountain and valley. People from Africa can live in Alaska and vice versa, without appreciable genetic shift. To make these adaptations, humans are able to use a vast array of tools and techniques, including coats, heaters, air conditioners, lighting, and shades. The flexible human species can adapt between legality and illegality, and among the various forms of illegal action. Parts of this book deal with adaptation in its many forms. I consider how people exploit new crime opportunities with changing technology—such as the emergence of Internet fraud. I also examine how people adapt to reduced crime opportunities—sometimes by following the law more often.

Not only offenders but also potential victims adapt to a changing environment. People manufacture automobiles with better locks and other theft-thwarting features. Urban parks are rebuilt for security, and public transit systems are designed to keep people from jumping turnstiles, painting graffiti, or mugging customers. Many forms of situational crime prevention have removed crime opportunities, without adding arrests or criminal justice costs.

Although new crime forms emerge, older forms sometimes adjust to new circumstances. For example, shoplifters can learn to avoid the sweep of surveillance cameras or find new targets as old ones become less suitable for theft. Credit-card fraudsters try to adjust when new procedures interfere with their efforts. Older crime forms might disappear. Safecracking faded as safes became formidable and easier crime targets emerged.12 Drug markets can shift from heroin to cocaine, then back again in response to availability and fashion, as well as the morbidity and mortality of users. Once-popular drugs fade and new designer drugs emerge.13 Those preventing crime also learn to do a better job, as we shall see. Chapter 10 is entirely devoted to adaptation. Crime’s variety convinces me more than anything else that we must study it as a living process.14

Crime Rhythms and Movement

Imagine a police cadet, age 22, studying at the police academy. He starts with an image of crime derived from television. Then the academy teaches him by the book, without going into crime’s detailed realities. After graduating from the academy, the new officer goes to work, only to be surprised about crime’s regular and irregular features.

Crime has a metabolism, a rhythm of life responding to other rhythms. The daily life of a city provides the targets for crime and removes them. The sleeping, waking, working, and eating patterns of offenders affect the metabolism of crime.15 You can see the metabolism of the city by going several stories up in a building, pulling up a chair, and watching people and vehicles over the course of an entire day, then into darkness.

The daily movement of activities away from residential areas makes burglary easier. And so the metabolism of the metropolis is essential for understanding how crime thrives. We must study these rhythms of life if we wish to understand crime, for the energy of crime draws from the energy of life. Residential burglars depend on weekday flows of people away from home. Certain robbers rely on the motion of people near money machines. Offenders have their own metabolism, perhaps sleeping late to recover from a late night’s partying. Residential burglars depend on the rhythmic shift of residents away from home in the morning, and they better watch out for their return later. Each community breathes both illegal and legal activity, with offenders, targets, and guardians all moving with respect to one another. Accordingly, street prostitutes select “strolls” that make it easier to pick up customers on their way home from work. Robbers heed the motions of their victims as well as the motions of others who might interfere with their crimes. For example, they notice people who stagger home, drunk and alone. A car thief responds to a vehicle moving into his range and to the owner’s walking out of sight. Burglars save more difficult tasks for times when they have pickup trucks available to remove heavier items.

Movements include the offender’s trip to crime, the victim’s trip to be attacked personally, or the guardian’s motion away from the site of the target. Accomplices move toward a common location from which they commence their joint offending. We must also consider the trip after crime, with burglars and thieves evading potential captors and going to unload the loot.

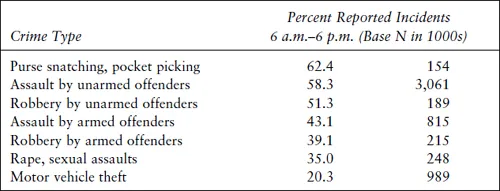

The motions of the living metropolis, city, town, village, and countryside greatly affect vulnerability to and security from every type of criminal activity. Crime is in motion—daily, hourly, and momentarily, on large scale and small. Exhibit 1.2 shows that the daytime share of crime varies greatly from one offense to another. While 62 percent of purse snatching and pocket picking occurs between 6:00 a.m. and 5:59 p.m., only 20 percent of motor vehicle theft takes place during those daytime hours. While unarmed assaults and robberies tend to occur during daytime, the armed versions of the same crimes tend to take place at night. (If you look ahead to Exhibit 1.4, you will see that crime events can shift greatly by a single hour of day and night.) Clearly crime has a metabolism that we must try to understand.

Growth and Crime

Mark Twain explained growth as basic:

What is the most rigorous law of our being? Growth. No smallest atom of our moral, mental, or physical structure can stand still a year. It grows—it must grow; nothing can prevent it.16

Exhibit 1.2 Victimizations Before 6:00 p.m., United States, 2002, Selected Offenses

SOURCE: National Crime Victim Survey, 2002, Tables 58 and 59. Available from Bureau of Justice Statistics, www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/abstract/cvusst.htm.

NOTE: This table omits those crime types whose times are unknown or unavailable more than 10 percent of the time. Non–personal property crimes (e.g., burglary) are subject to more error; these victims often discover that an offense occurred some time afterward.

Young bodies grow into crime-prone ages, affecting not just individuals but the crime rates of large societies. Criminal participation of many types begins and peaks during teenage years, often extending at high rates into the 20s. However, many crimelike behaviors begin at earlier ages. Children steal candy from stores at ages too young to be treated criminally. They poke and shove one another at young ages; but teachers and parents can normally manage transgressions that small kids with puny muscles ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Exhibits

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- How to Use This Book

- Part I. Introduction

- Part II. Crime Within a System

- Part III. Crime’s Relationships

- Part IV. Attack and Defense

- Part V. Synthesis

- Epilogue

- Crime Ecology Glossary

- Appendix A. Main Points From Crime and Everyday Life

- Appendix B. Exhibits

- Index

- About the Author