- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Group in Society

About this book

The Group in Society meets the challenges of teaching courses on small groups by revealing the full complexity of small groups and their place in society. It shows students the value of learning how to carefully study a group?s history and context, rather than merely learning a fixed set of group participation skills. This text brings together disparate theories and research (from communication, social psychology, organizational and managerial studies, and sociology) in a way that helps students make sense of a complex body of scholarship on groups.

Features & Benefits

Features & Benefits

- Part I – Theorizing Groups: builds a strong theoretical foundation, exploring social theory and the group, forming and joining groups, the life and death of the group, and changing society through group life

- Part II – Understanding Groups in Context: explores the histories, purposes, memberships of a variety of groups—including juries, families, executive committees, study groups, and political action groups—thus enabling the student reader to speak clearly about group formation, norms, roles, tasks, and relationships. Detailed end-of-chapter case studies explicitly connect with the concepts, theories, and empirical findings introduced in each respective chapter; examples include the powerful group bonds of the modern terrorist cell; the wired network of groups in the anti-Globalization movement; and the deliberation of a jury in a murder trial

Teaching & Learning Ancillaries

- Teaching resources are available at http://groupinsociety.la.psu.edu/ and include chapter summaries, discussion questions, and practical applications; a sample course schedule; Embedded Systems Framework PowerPoint slides; group project assignments, group project worksheets, and a group project description and contract; and links to useful Web resources such as small group teaching resources and active wikis on small groups.

- An open-access student study site features e-flashcards, practice quizzes, and other resources to help students enhance their comprehension and improve their grade.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Group in Society by John Gastil in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sprachen & Linguistik & Kommunikationswissenschaften. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

An Introduction to Small Groups

CHAPTER 1

SMALL GROUPS UP CLOSE

Groups have their detractors. From the left, playwright Oscar Wilde quipped that “the problem with socialism is that it takes up too many evenings.” From the right, pundit George Will once observed, “Football incorporates the two worst elements of American society: violence punctuated by committee meetings.” From outer space, Captain James T. Kirk offered that “a meeting is an event where minutes are taken and hours wasted.”1

Our distaste for group life has justification. Small groups can create more problems than they solve, and they can wreak havoc in the service of dubious or even evil purposes. But as our own experiences already attest, groups can prove indispensable and help us achieve great ends. After all, if groups truly had nothing to offer, how could they be so prevalent? When employers look to hire, the ability to work effectively in teams ranks among the most desired qualities. Over 90% of the Fortune 500 companies use groups daily, with managers spending 30–80% of their days in meetings.2

At the highest levels of power, groups also play prominent roles. Many countries entrust their most challenging legal questions not to single individuals but to panels of judges, like the U.S. Supreme Court. The largest cities on Earth make their planning decisions through a small municipal board of elected or appointed officials, rather than leaving those matters to a city manager, mayor, or executive. The question of whether and how to go to war typically falls not as much on a head of state but on a security committee, a war council, or another assembly of generals and officials.3 We have also turned to small groups when seeking to resolve international disputes4 and intractable domestic policy debates.5

Even decisions traditionally made by individuals may be just one retirement away from conversion into a group process. When Ben Bernanke took over the Federal Reserve in 2006, he brought with him a different idea of how to run the nation’s banking system. Vincent Rinehart, who worked at the highest levels of the Federal Reserve for many years, observed that Bernanke’s goal “is to have the committee be more actively involved in the deliberation of U.S. monetary policy. He doesn’t want to be the iconic figure that Alan Greenspan was.” Bernanke believes that if you have “more people deliberating on policy, maybe on average you make a better decision.” The Fed chairman believes, Rinehart explains, in “the wisdom of crowds.”6

That phrase was the title of a bestselling book by New Yorker business columnist James Surowiecki. Replete with compelling anecdotes and research, this book probably did more to burnish the reputation of small groups than any single event in our time. Reading Surowiecki, one comes to recognize that the virtues of group-level thinking appear throughout our culture. Even the TV studio audience of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire guesses correctly 91% of the time, a far better performance than the 65% accuracy rate obtained by the experts contestants call by “phoning a friend.”7 Unfortunately for small-group researchers, Surowiecki was more interested in the “mob intelligence” of very large, loosely connected “groups,” such as a network of stock traders. As a result, his analysis only modestly advanced our understanding and appreciation of small groups.

If groups serve us so well, how is it that we overlook and underestimate them? One reason is that small groups are inextricable from daily life and, as such, become taken for granted. Above all else, the family group serves as the most basic social unit: In spite of tremendous cultural variation, in some form or another, the family proves nearly universal across the wide span of geography and history. When we venture beyond the home, we enter the world of friendships and social ties that, again, center on groups of manageable size. Even with the Internet’s spawning of Friendster, Facebook, MySpace, and other social networking sites, most people still report having only two or three close friends in their inner circle, wherein they discuss the most important events in their lives.8 Then teams, clubs, and hundreds of other small group forms occupy much of our professional, political, and community lives and help us build and maintain our social identities. When asked by inquisitive researchers, people will admit that they value their intimate social groups more than the larger social categories and organizations to which they belong.9

Immersed in a sea of small groups, we develop commonsense or “folk” theories about how to behave in groups—some true, some not—but we don’t like to think that participation in groups requires special skills or knowledge. After all, being in groups is as routine as tying our shoes or having a conversation. Surely we don’t need special courses, seminars, or books to do something so basic. It’s an ironic notion when one considers how quickly we turn to books and counselors to help us solve our dyadic crises in marriage and intimate relationships. Groups pose even graver challenges yet get a fraction of the ink on the popular bookshelf.

Understanding Groups

To think systematically about how we behave in groups—and how groups shape our social world—we need to use precise language to discuss them. Concepts, such as group cohesion, leadership, and diversity, require clear definitions, and the theories we build need to deploy these concepts carefully. Moreover, the research we conduct on groups must build and test our theories in a way that helps us evaluate plausible accounts of groups from implausible ones. This chapter sets the groundwork for understanding group concepts, theory, and research, but we begin by defining the most important concept of all—the small group itself.10

A definition might seem a trifling thing. After all, we know a small group when we see one. Or do we? When does a small gathering of neighbors become integrated enough to begin to look like a group activity? If a small gathering of fans celebrating a victory begins rioting, at what point does it cease being a group and spiral into a mob? How complex can a small business grow before changing from a group to an organization? At what point does a small clan grow into a community? If a jury is a small group, is a city council also a group? By defining a small group more precisely, we can answer each of these questions and get on with the business of understanding the behaviors and impacts of groups in society.

Group Size, Copresence, and Boundaries

The foremost question for many may be, How large can a small group become before it ceases to be small? Throughout this book, the term group serves as a shorthand term for small group, but the smallness of groups is always implied. It is relatively easy to see that the minimum size of a group is three people. With only two people present, we have a dyad, a pair of people who can communicate back and forth and make decisions together. Adding just one more person to the mix makes possible majority-minority splits, introduces potential competition for attention, and otherwise changes the fundamental nature of the social unit.

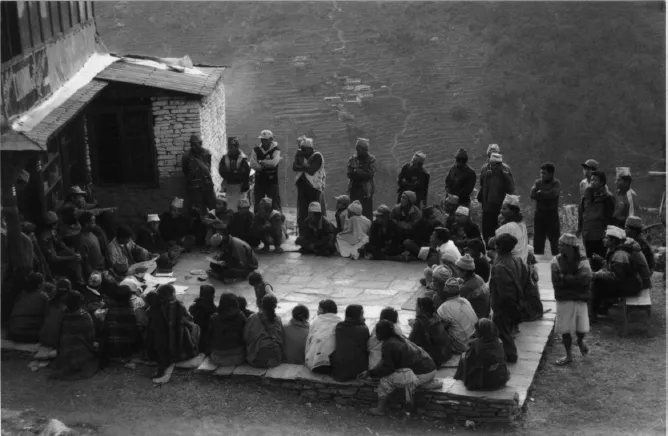

Some investigators would have us draw a sharp upper boundary by claiming that a small group can be no more than fifteen members in size.11 Such a restrictive definition would exclude from our analysis social entities that are more like a small group than anything else. A gathering of rural villagers to conduct local business, for instance, looks and behaves more like a small group than, say, a large organization or diffuse community.

A better way of limiting the size of a small group is to require that every group member have a sense of every other member’s copresence. When people exist as members of a small group, they are together in this minimal sense, each aware of every other individual in the group.12 They may not (yet) know each other’s name, let alone one another’s personal histories or preferences, but they are all part of each other’s present reality. In the case of a virtual group, they may not all be aware of who is or is not present online—let alone paying attention—at a given time, but they do know what set of people make up the group.

When these Nepalese villagers met to weigh the benefits and costs of electrification, were they too numerous to constitute a small group?

Credit: Photo courtesy Alisa Bieber.

But size alone does not determine copresence. Even smaller groups might fail to meet this criterion and thereby constitute something other than a small group. My three closest friends might all e-mail me on the same day, but that makes me the center of a social network, not the convener of a group. A vice president might designate a set of ten employees as an informal “leadership team” in a company, but if those ten people never meet together, they share a certain status or title but not a group membership.13

A related consideration is the sense of a group’s boundaries, an understanding of the group as a defined entity. Group theorists have a term for this phenomenon, which they call entativity. A group has this quality to the degree that “members of a group are perceived as being a coherent social unit.”14 Coherence in this sense means that the group members—and outside observers—can at least identify the boundaries of the group’s membership. Many groups, such as open-enrollment support groups, have members joining and leaving with great regularity, but if they remain small groups, they still have sufficient coherence at any given time.

Communication, Goals, and Interdependence

There is more to a group, though, than simply having a sense of bounded copresence. There is also the matter of what groups do, and that consists of communication in the pursuit of group goals that require effective collaboration.

To count as a group, a social entity must have regular member interaction. Most commonly, this means either speaking, signing, or typing to one another, though some groups’ most important interactions are physical or nonverbal, as in the case of a play group, jazz band, or work crew. If communication does not occur with any regularity in a group, there may exist a social gathering or relationship network of some kind, but not a group. After all, the very idea of grouping entails an ongoing pattern of communication among the group’s members.

What counts as “ongoing” is also a question. Much of the available research looks at experimentally formed zero-history groups, which literally have no history of working together. Typically, they stay together for only a brief period of time, ranging from a period of minutes to a handful of meetings over the course of a few months. But even these zero-history groups are still groups; they simply have different social contexts and connections. In the case of the prototypical experimental group of undergraduates, the participants have followed similar paths to membership, suc...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Brief Contents

- Detailed Contents

- Preface

- PART I: AN INTRODUCTION TO SMALL GROUPS

- PART II: DISCUSSIONS AND DECISIONS

- PART III: ROLES, RELATIONSHIPS, AND IDENTITY

- PART IV: INTEGRATION AND CONCLUSION

- References

- Credits

- Index

- About the Author